The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Chapter 5: Cash Preparedness and Capacity

Summary

Key findings

- CVA preparedness and capacity remains a priority, though needs are changing.

- Economic volatility, including inflation and depreciation, has emerged as a challenge for emergency preparedness.

- Adapting CVA in contexts of high inflation and depreciation requires inter-agency planning and preparedness through CWGs.

- Resources should be targeted to address priority capacity gaps, including data and digitalization, as well as to increase CVA preparedness and capacity more broadly.

- There are notable disparities in the views of different stakeholder groups about the challenges faced by national and local organizations in scaling up CVA.

- The new cash coordination model gives the opportunity for CVA to be part of standard preparedness planning in the humanitarian system.

- Most large humanitarian organizations invest in CVA preparedness and capacity development, though the degree and emphasis of investments vary.

- As CVA tools and guidance continue to be developed there is need for more focus on uptake.

Strategic debates

- Given that the humanitarian system and context are changing, what are the priorities for CVA preparedness and capacity development?

- Does the new cash coordination model offer an opportunity to improve CVA preparedness and capacity?

- How should decisions be made about the balance of investment in preparedness for in-kind assistance and CVA, given that CVA is the modality of choice for most people affected by crisis?

Priority actions

- Donors and humanitarian leaders should seize opportunities to engage with strategic discussions around funding and innovative financing to increase investment in system level CVA preparedness and capacity. This includes linkages between humanitarian and development action.

- The CAG and CWGs should foster coherent approaches to CVA preparedness and capacity. Opportunities within the HRPs should be harnessed and linkages with Social Protection advanced.

- Donors, implementing agencies and researchers should continue to generate learning and good practices on the use of CVA in contexts of economic volatility.

- Communities of practice on CVA preparedness and capacity should be established at country, regional and global level to share and learn, identify strategic gaps, and progress collaborative initiatives.

- All actors should advocate for predictable, multi-year funding for CVA preparedness and capacity development, with an emphasis on strategically important gaps. Where international actors receive preparedness funding, capacity needs of local implementing partners should be prioritized.

- Donors should collectively support CVA preparedness and capacity development as a key strategy to increase the scale and effectiveness of CVA. Investments should prioritize local actors direct funding wherever possible.

CVA preparedness and capacity remains a priority

Systemic, organizational and individual preparedness and capacity is vital if ambitions to increase the scale, quality, efficiency and effectiveness of CVA are to be met. There was near consensus among survey respondents that CVA preparedness has improved; 86% perceived that their organization has improved its preparedness and capacity for CVA (up 8% since 2020). Perspectives of almost all organization types were similar – between mid to late 80%.

Findings in the Grand Bargain Independent Review, where many organizations reported having increased their institutional capacities to deliver cash assistance at large-scale, support these survey results1. That same review gave examples such as UNHCR’s enhancements to its financial and administrative systems; WFP’s update of its institutional policy on CVA; and investments in guidance, tools, and staff skills development by Care International, Mercy Corps, Oxfam, Save the Children, Trocaire, UNFPA and World Vision International. In addition, the Red Cross Red Crescent (RCRC) reports that national societies have expanded their capacity making many ‘cash ready’ (discussed further below). Examples of local actors increasing their cash readiness are given in Chapter 3 on Locally-led response.

Much as progress is recognized, the need for further investment in preparedness remains a priority. Twenty-five percent (25%) of survey respondents perceived that limited capacity of organizational systems and processes was the biggest challenge to increasing the quality of CVA. Thirty-four percent (34%) of survey respondents believed that strengthening organizational systems and processes offers one of the biggest opportunities for growing the use of CVA within existing funding levels. This compares favourably to 2020 when 42% of survey respondents perceived limited capacity of systems and processes as the most significant challenge to scaling CVA.

Graph 5.2: The need for further investment in preparedness remains a priority

Continuing capacity gaps are not surprising given that the use of cash is growing and evolving, and the operating environment is rapidly changing. Encouragingly, management support is perceived as less of a challenge than previously – 11% of survey respondents highlighted this as one of the biggest challenges to scaling up CVA compared to 19% in 2020.

Box 5.1: Definitions of emergency preparedness and capacity

Emergency preparedness: “Is the knowledge and capacity developed by governments, recovery organizations, communities and individuals to anticipate, respond to and recover from the impact of potential, imminent or current hazard events, or emergency situations that call for a humanitarian response.” (IASC)

Capacity: Definitions of ‘capacity’ in humanitarian and development contexts vary but at its simplest, it is the “ability of individuals, institutions and societies to perform functions, solve problems, and set and achieve objectives in a sustainable manner.” (UNDP 2009)2

Kamstra (2017) identifies3 three different types of capacity to be considered:

- Individual: experience, knowledge, technical skills, motivation, influence.

- Organizational: collective skills, internal policies, arrangements, and procedures that enable them to combine and align individual competencies to fulfil their mandate.

- System-level: the broader institutional arrangements which enable or constrain individual or organizational capacities, including social norms, traditions, policies, and legislation.

To increase the use of CVA and continue to improve quality, an understanding of where the capacity gaps are greatest and their impacts – both current and potential – is key. For example, when asked about the biggest challenges to improving the management of recipient CVA data: 43% of survey respondents perceived that understanding of data responsibility is not effectively mainstreamed across teams implementing CVA; 42% perceived limited IT and systems capacity; and 25% saw limited legal and compliance/due diligence capacity as significant issues.

The implications of such capacity gaps need to be considered, with analysis directing investments made in capacity development. Gaps related to data protection and technology come with risks for recipients in terms of mismanagement of their personal data; legal and ethical concerns; compliance and liability issues; and so on. The implications of these gaps are also explored in Chapter 7 on Data and digitalization. Equally, when asked about increasing the use of multi-purpose cash (MPC), 33% of survey respondents identified limited staff capacity as one of the biggest challenges. In this case, capacity gaps may lead to MPC not being used even when it is a preferred and appropriate option or results in poor quality programming.

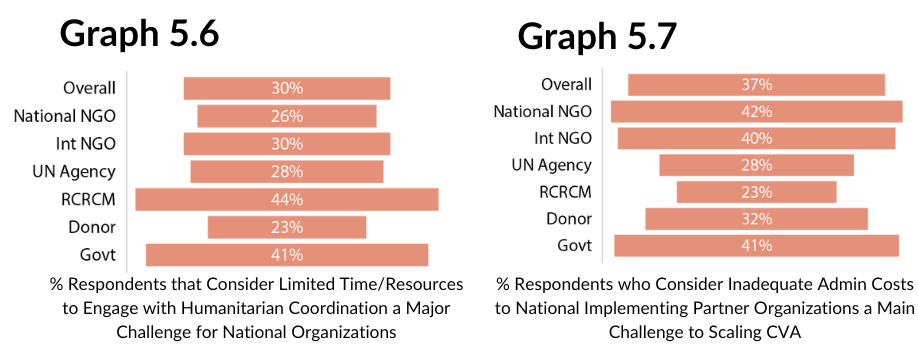

The survey also asked about the main challenges that national organizations face in scaling up their delivery of CVA. There are notable disparities in views between the responses of different stakeholders, with capacity limitations considered a more significant challenge by respondents from international organizations than national NGOs (see Graphs 5.4 and 5.5). Several key informants considered that this reflected a lack of trust in local actors’ abilities – a view also highlighted in some recent publications4.

Many key informants pointed to the lack of donor and international agency investment to enable local actors to strengthen their capacity. Reference was made to a lack of technical training tailored to local actors’ needs5 and, particularly, a lack of resourcing for the requisite operational systems and processes (see also Chapter 7 on Data and digitalization). Several key informants noted that limited resourcing also contributes to staff retention challenges for local organizations, given salary disparities with international agencies, creating a major challenge to maintaining capacity in the medium to longer term. This is an issue well documented across the humanitarian system6, affecting CVA alongside all other areas of work.

Several local actors noted that limited staffing and resourcing is a critical barrier to engagement in coordination forums – a point that emerges from our survey, which found staffing to be the fifth most cited barrier (30%) to engagement.

“More trust is needed that they (local actors) can handle CVA programmes – this is basically going against our comfort zone.” KII.

“Approaches to funding that tend to be short-term, ad hoc, and have minimal support costs also do not enable local partners to build the capacity and systems necessary for a quality CVA response.” Lawson-McDowall and McCormack (2021).

Thirty-seven percent (37%) of survey respondents consider inadequate administrative costs to national partner organizations to be a main challenge to scaling CVA. Key informants criticized international (especially UN) agencies for not passing on an equitable share of administrative budgets to local partners. They commented that this perpetuates a circular problem, with donors and international actors citing due diligence concerns, but not providing resources to enable local actors to make the necessary investments in systems to change the situation. Several studies published since 2020 also comment on this issue7.

While action is overdue, there does seem to be growing momentum to address the issue of overheads. For example, at the end of 2022, IASC published guidance on provision of overheads to local partners8. This, together with the political push in the Grand Bargain, is seen as having the potential to be effective in driving change in policy and practice9. At the same time, many international actors have now committed or re-committed to supporting local CVA capacity as well as developing their own. Alongside initiatives by the RCRCM (discussed below), other approaches are also covered in Chapter 3 on Locally-led response, including those of the Collaborative Cash Delivery (CCD) Network, the Start Network, CashCap and Share Trust.

WFP refers to ‘country capacity strengthening’10 (differentiating it from its ‘internal capability development’ which refers to learning and training for its own staff) within which it commits to localization. It reports that in 2022 it supported 65 governments to design and implement their own CVA11. UNHCR’s Cash Policy (2022–2026) includes a commitment to advocate, coordinate and deliver CVA through collaborative approaches, working with ‘governments, building and strengthening strategic partnerships and alliances, including with sister agencies, NGOs, persons of concern and the private sector’12 and notes that collaboration with local partners will be at the core of implementation.

Cash preparedness and capacity needs are changing

The nature of cash preparedness is changing as the use of CVA increases and evolves. For example, in recent years, the focus on linkages between CVA and social protection systems has increased, and greater attention has been given to anticipatory action with implications for preparedness (also discussed in Chapter 6 on Linkages with social protection and Chapter 9 on Climate and the environment). Equally, contextual changes have demanded adjustments to ways of working – with high rates of inflation in many countries bringing new considerations, and new or evolving technologies offering new preparedness opportunities. The increasing array of organizations involved in CVA also has implications for cash preparedness thinking and action.

In 2022, research explored cash preparedness within the context of the food crisis in East Africa13 – drawing on the perspectives of over 200 practitioners to understand what changes would be needed for cash responses to be faster and more effective. The need for better collaborative partnerships and different ways of working was identified as essential. Collaboration between humanitarian organizations and donors to mainstream shock responsive or crisis modifier mechanisms was emphasized as important, with greater flexibility needed by both parties to make timely changes to operational plans and funding agreements. The research also found the need for greater flexibility and new ways of working extended to how operational agencies work together. It identified possibilities to improve response efficiency and effectiveness including (subject to context) the possibility of prepositioning staff and logistics to conduct targeting exercises or develop recipient lists (by using existing lists from other programmes, humanitarian agencies or through partnerships with financial service providers [FSPs]). The research concluded that such opportunities would require stronger relationships between those involved in CVA, with relationship and trust building becoming an essential part of CVA preparedness.

Reflecting on ways of working, the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report highlighted the need to strengthen collaboration and partnerships between humanitarians and FSPs, including mobile money organizations, to ‘ensure solutions are flexible and meet recipients’ short- and long-term needs’. The need for more effective relationships between these parties continues to be seen, though views differ as to how these relationships can be maximized. This is explored further in Chapter 7 on Data and digitalization.

Graph 5.8 The role of payment aggregators in cash preparedness

A major change since the 2020 report is the increased focus in the sector on linkages between CVA and social protection. A key enabler for successful linking is investment in preparedness and capacity strengthening. This can be unpacked at different levels in terms of humanitarian organizations’ internal institutional preparedness and capacity, as well as preparedness planning at response level. Humanitarian organizations are at a relatively early stage in the journey of linking CVA and social protection, with major gaps in skills and experience identified as a challenge to progress.

“Humanitarian agencies and donors are increasingly engaging in SRSP to increase preparedness and response capacities for humanitarian disasters.” Donor.

It seems logical to expect efforts to capitalize on the linkages between CVA and social protection will follow a similar evolution to what has been seen over the past decade with the scaling up of CVA more broadly – a process which required clear organizational buy-in and policy direction, followed by specific investments to develop capacities, and work to make institutions fit for purpose. Arguably, linking CVA and social protection may be even more complex as it requires developing capacities across different disciplines and across different types of institutions. As seen in Box 5.2, survey respondents most frequently cited gaps in technical capacity and organizational systems and processes as a challenge to linking humanitarian cash assistance with national social protection systems and programmes (see Chapter 6 for more on social protection and CVA linkages).

Inevitably, organizations are at different stages in the process of creating linkages between CVA and social protection. With interest in linkages spurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, those organizations (primarily UN) that were more advanced in their thinking in this area, and that were further along the process of building capacities and institutionalizing this approach, were generally better placed to act14.

Box 5.2: What are the most significant challenges in linking humanitarian cash assistance with national social protection systems and programmes?

- Limited technical capacity of humanitarian staff to engage with social protection institutions and programming: 25.6%

- Limited technical capacity of social protection staff to engage with humanitarian response: 21.6%

- Limited organizational systems and processes of humanitarian organizations: 12%

Overall, organizations note challenges including difficulties in defining an organizational position or strategy guiding their agency’s approach to linking; recruiting appropriate skill sets in social protection; linking social protection and humanitarian action at HQ and response level; and making the topic and tools accessible for staff teams. The relatively small pool of technical expertise bridging both sectors is currently a major bottleneck to progress. While tools and approaches exist, there are not yet enough people with the requisite skills and experience to carry out assessments and analysis to inform effective decision-making. CashCap, for example, has faced difficulties in recruiting advisers with the expertise to support capacity development requests on this topic.

The challenges of economic volatility

Since 2020, economic volatility, including inflation and depreciation has arisen as an emerging challenge for emergency preparedness. As economies have continued to be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the invasion of Ukraine and many other factors, global inflation has persisted as a trend to be addressed in the medium-term. Forty-nine percent (49%) of survey respondents identified this as one of the highest risks associated with CVA that need to be addressed. Notably, inflation and depreciation hardly received a mention in the previous State of the World’s Cash reports.

Since 2020, economic volatility, including inflation and depreciation has arisen as an emerging challenge for emergency preparedness. As economies have continued to be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the invasion of Ukraine and many other factors, global inflation has persisted as a trend to be addressed in the medium-term. Forty-nine percent (49%) of survey respondents identified this as one of the highest risks associated with CVA that need to be addressed. Notably, inflation and depreciation hardly received a mention in the previous State of the World’s Cash reports.

In 2021, in response to pandemic-related inflation, research15 explored, with a particular focus on MPC, the adaptations needed for CVA programming in contexts of inflation, depreciation and currency volatility. Key findings included:

- The importance of preparedness for appropriate and timely adjustments to programming.

- Programmatic flexibility, including from donors, to respond to changing circumstances.

- The role of advocacy with governments, FSPs and regulators to alleviate the impact of inflation and depreciation.

- The harmonization of analysis and approaches across actors, e.g. through Cash Working Groups (CWGs).

- The need for learning across a diversity of country contexts, noting, in general, a tendency to compare situations in a country with neighboring countries or countries in the same wealth range, while on this issue there is valuable learning from emerging experiences across the globe.

This documentation was widely used in 2022 and 2023, including learning exchanges with the World Bank, particularly as global inflation was exacerbated by the invasion of Ukraine, leading to spiralling costs of fuel and food commodities. While there are some questions as to the efficacy of CVA in inflationary contexts, there appears to be continued support for CVA and concerted efforts by individual agencies, as well as the Donor Cash Forum (DCF) and global Food Security Cluster to ensure CVA is adapted and flexible. The DCF, building on its earlier endorsement of the Good Practice Review on Cash Assistance in Contexts of High Inflation and Depreciation16, has included inflation as a component of its priority on challenging environments.

Adapting CVA in contexts of high inflation and depreciation requires forward planning and pragmatic solutions, tailored to the specific economic, political, and humanitarian context. There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to be adopted. Experience shows the need for flexibility and increased inter-agency planning and preparedness through CWGs including the need for16:

- Clear and predictable processes developed by CWGs to adjust transfer values, with common strategies, agreed criteria and thresholds to trigger the review of transfer values. A commitment to use the adjusted values is key.

- A solid understanding of the economic context and outlook with joint market monitoring and forecasting to enable advance planning and communication with donors on potential adjustments.

- Contingency planning based on potential economic scenarios, requiring CWGs to have a deeper understanding of the economic context to anticipate and develop scenarios and options for CVA adaptations so that all stakeholders are better prepared to adapt CVA.

- Increased monitoring of feedback from recipients to understand inflationary impacts and the efficacy of adaptations made during the response.

Policy commitments

Cash policies and commitments, which include references to cash preparedness and strengthening organizational capacities, are demonstrated by the increased use of CVA since 2020 (see Chapter 2 on CVA volume and growth).

Since 2020, some donors have made renewed commitments to CVA preparedness. This includes DG ECHO, which stated in its 2021 Guidance Note on Disaster Preparedness that it expected ‘partners to actively coordinate on cash preparedness and contingency planning, under the leadership of the Cash Working Group and in coordination with key social protection actors. This should include joint feasibility and risk assessments’18. DG ECHO reinforced this in its Thematic Policy Document on Cash in March 2022, emphasizing the importance of preparedness for adequate, timely and equitable assistance and in linking cash with social protection systems, including shock responsiveness19. While the DCF does not have preparedness as an explicit priority at present, it may be addressed through its current priorities, including coordination, social protection, interoperability, locally-led response and anticipatory action.

Several UN agencies have adopted new CVA policies since the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report, with commitments to preparedness and capacity. UNHCR published a new cash policy (2022–2026)20 which strengthens its position on cash. Adopting a ‘why not cash’ approach, it states that ‘Refugees, IDPs and others of concern will increasingly access CBI as the preferred modality of UNHCR assistance from emergency preparedness and response to the achievement of solutions’. IOM also published an updated cash policy (2022–2026), setting the overall direction for the use and scale-up of CVA as a priority modality of assistance across all programme areas. The policy states that it will use CVA as a catalyst for more comprehensive and sustainable solutions, linking humanitarian cash assistance with social protection systems, livelihood support and other development programmes where possible. For WFP, its commitment to cash preparedness is demonstrated in its latest cash policy (2023)21, which states that the policy complements and should be read in conjunction with other key policies and documents, including its Strategic Plan and Emergency Preparedness policy22. Most INGOs are reported to have made similar CVA preparedness policy commitments but these are captured in internal documents. The commitments of the RCRC to invest in national society development are discussed later in this chapter.

Cash preparedness – finding its place at the system level

Although CVA preparedness is widely embedded in individual organizations’ CVA policies and strategies, there has been a lack of clarity about collective preparedness responsibilities at the system level. This may be partly because the coordination of CVA has not, until recently, had a formal place in the humanitarian architecture.

Box 5.3: The IASC emergency response preparedness guidance23

The 2015 guidance consists of:

- Risk Analysis and Monitoring

- Minimum Preparedness Actions

- Advanced Preparedness Actions and Contingency Planning.

The guidelines are premised on the understanding that governments hold the primary responsibility for providing humanitarian assistance to women, girls, boys and men and sub-groups of the population in need. They outline how the international humanitarian community can organize itself to support and complement national action.

Following the IASC endorsement of the Cash Coordination model in March 2022 (see Chapter 4 on Cash coordination), new opportunities now exist to take a wider view and strengthen CVA preparedness at a system level in keeping with IASC guidance. For example, following the establishment of the global Cash Advisory Group (CAG) and agreement on the CWGs’ function within the humanitarian architecture, a common understanding of the role of CWGs in preparedness is emerging. Draft guidance charges CWGs with responsibility ‘for systematically integrating CVA, particularly multi-purpose cash transfers (MPC), into humanitarian responses and preparedness plans – wherever feasible and appropriate – to ensure coherence and avoid duplication of efforts’24.

Further, OCHA’s role related to cash is included in its 2023–26 strategy which states that ‘In light of OCHA’s global leadership on cash coordination, cash will be used whenever feasible and appropriate, and coordinated effectively. Multi-purpose cash can support a less siloed, more integrated, flexible and effective response that places agency and flexibility in the hands of people most impacted by crisis’25. OCHA also sets out its ambitions towards a greater focus on preparedness across the Humanitarian-Development-Peace system stating ‘humanitarian actors must better understand and support national and local capacities and structures; engage with partners across the HDP nexus and beyond to bring programmes and financing into fragile settings earlier’26. To achieve these aims and ambitions, it will be vital that OCHA adequately resources its leadership role in cash, a point which many key informants raised, as detailed in Chapter 4 on Cash coordination.

Developments in response planning guidance also provide opportunities to enhance CVA preparedness. For example, in 2020 OCHA published internal guidance on including CVA in Humanitarian Programme Plans27 and adjusted the Humanitarian Response Plan templates to allow for the inclusion of an (albeit optional) chapter on multi-purpose cash. The Humanitarian Programme Cycle process is now being further revised, with a focus on putting people affected by crisis at the centre (changes are due to come into effect in 2024) – which could provide increased focus on the importance of modality choice.

Preparedness and capacity investments

Most humanitarian organizations invest in CVA preparedness and capacity development, though the degree to which that is possible, particularly for local actors, and the emphasis of investments vary.

Research in 2022 focused on scaling the use of CVA in28, identified a tension between the investments made in cash and in-kind assistance preparedness. It highlighted the need for institutional dialogue between those involved in logistics and CVA to review the relative investments made in the pre-positioning of in-kind assistance compared to strengthening cash preparedness. It also found that some donors prioritize preparedness for in-kind assistance, particularly food aid. Thirty-two percent (32%) of survey respondents identified the option of investing in more CVA preparedness and reducing spending on pre-positioned, in-kind stocks as one of the biggest opportunities for the growth of CVA within existing funding levels of donors and implementing partners.

Many key informants felt that funding for CVA preparedness and capacity development has not increased or may even have decreased since the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report – despite the increased use of CVA and recognition of the importance of preparedness and capacity in enabling effective CVA. The concentration of CVA funding to a smaller number of organizations (see Chapter 2 on CVA volume and growth) may be contributing to this perception, potentially affecting the resources available to different organizations to invest in CVA preparedness and capacity. The Grand Bargain Independent Review touches on this, stating that what ‘funding is available from government donors is not allocated equitably across actors, with multilateral organizations receiving the lion’s share’ 29. However, as funding for CVA preparedness and capacity strengthening is generally not tracked nor publicly available, views about trends cannot be evidenced in numbers.

CashCap supports system-level CVA capacity working in partnership with CVA stakeholders at country, response, regional and global levels. In 2022, 32% of all active Cash Working Groups globally drew on CashCap for its technical and/or coordination support. Alongside CWG coordination and technical advisory support, there was increased demand for support in complex multi-stakeholder collaborative arrangements to implement CVA and in establishing and operationalizing humanitarian CVA/social protection linkages. The average length of each support mission was 12 months or longer.

Box 5.4: CashCap’s Strategic Plan (2022–2024)

Strategic focus areas

- Strong local and national leadership on cash and voucher intervention. It aims to scale-up its investment in local and national partners working with CVA in part by advocating for change in the humanitarian system to shift the power to local and national levels.

- International and national actors are better equipped to provide quality coordination of CVA. To achieve this, it will provide coordination expertise for major crises, scale-ups and initiatives to enhance the impact of interventions. It will provide transitional support during the implementation of the newly adopted cash coordination model, in close collaboration with the global CAG.

- Quality CVA is delivered every time, through innovative and integrated approaches tailored to the specific context. It supports new and ambitious ways to increase access to quality CVA. This includes coordination with social protection systems, working with partners with less experience of CVA, collaborating with non-traditional stakeholders, and bridging work across the humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding sectors.

The lack of direct funding from international donors to local and national organizations is well documented and while it is not a CVA-specific issue, there are specific impacts including in terms of CVA preparedness planning and capacity investments (see also Chapter 3 on Locally-led response). With recent donor commitments to increased multi-year, and often flexible, funding for many international actors 30, there is a clear rationale to ‘pay forward’ to partners. But, according to the 2022 Grand Bargain independent review there is ‘no evidence in the self-reports to suggest progress in aid organizations passing down the flexible or multi-year funds they receive to their implementing partners’29. Donors may wish to make this a requirement of their CVA funding as they continue to explore options for directly funding local actors.

While progress towards the direct funding of local and national organizations by international donors remains slow, other mechanisms such as pooled financing, sub-granting, and partnerships are providing some avenues for financing CVA preparedness and capacity strengthening work. For example, the CCD Network and the START Fund offer their members dedicated funding and resources for capacity strengthening. Equally, some CWGs (including Ethiopia, Somalia, and Syria) have reported fundraising from traditional humanitarian donors to support the activities of their members, including funding capacity efforts.

“Organizational preparedness has increased a lot in the past few years. There are currently 73 Red Cross and Red Crescent national societies investing in cash preparedness compared to 14 that were engaged in cash preparedness six years ago. […] National Societies use a set of standard guidance and tools to measure their own organizational and operational preparedness and assess their progress.” Red Cross & Red Crescent Movement.

The RCRC Movement reports significant success in terms of National Society CVA preparedness by taking an organizational development approach. In 2021, over 60 national societies were reported to be ‘cash ready’ – meaning they are considered able to provide timely, scalable, and accountable CVA32. It is also reported that national societies being cash ready has contributed to a growth in funding opportunities, increased credibility, visibility, participation in coordination fora, and greater policy influence33.

Some key informants noted that the local and national actors’ technical capacity to design and deliver CVA can be addressed through publicly available capacity strengthening initiatives (e.g. CashCap and CALP) and that this is already occurring at national and regional levels. However, some also noted that the main gaps in capacity are institutional and broader than cash and that institutional capacity gaps directly affect local and national actors’ abilities to design and deliver CVA in ways that enable them to gain CVA experience and access humanitarian financing for cash (see Chapter 3 on Locally-led response).

Training as part of individual capacity development

Key informants were unanimous that almost every humanitarian practitioner now has some degree of CVA awareness. At the same time, they reflected on the continuing need to ensure basic CVA skill sets across all functions, with particular mention made of support functions. These reflections were also seen in the survey, with 29% of the respondents perceiving that increasing staff capacity offers one of the biggest opportunities for the growth of CVA and 24% perceiving that limited staff capacity is one of the biggest challenges to increasing its quality.

When asked about national organizations specifically, 37% of the survey respondents perceived limited staff capacity as one of their main challenges in scaling up their delivery of CVA. In addition to basic CVA skills, some interviewees expressed the need for national organizations to be able to access more training in specialist areas and more contextualized support. Some key informants spoke of the need for international organizations to ‘pay forward’ the benefits they receive from funding for capacity development. In the context of training, some advocated for a collaborative inter-agency approach, with places offered for free or at a reduced rate for those that are financially constrained.

A priority action identified in the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report was that course developers ‘should reinforce e-learning and self-paced learning as flexible and accessible approaches’. Much as progress was already being made on this, COVID-19 served to further catalyze the digitalization of training. There continues to be strong demand for online training, with demand for in-person training again increasing with each approach having different strengths and limitations.

Box 5.5: Shifting training landscape

Overall, more people can be reached through e-learning courses and online training (a mix of e-learning and facilitated learning) which reduces attendance costs and makes training more accessible than in-person training. E-learning and online learning reduces (but does not eliminate) financial barriers to training, with these options often more environmentally friendly compared to face-to-face training. Where connectivity is an issue, e-learning and online training is not always a viable option. Further, social interactions are hard to replicate in online settings, and the longer period of time over which online trainings are spread make it more challenging to maintain engagement. The demand for such training was elevated during COVID-19 and remains strong. For example:

- CALP converted its flagship 5-day training on Core CVA Skills for Programme Staff into an online twelve-week course. Applications for these courses have been greatly over-subscribed.

- CALP online courses have achieved high completion rates, with 71% of participants completing the course over the last two years, a figure that compares favourably to most online distance learning courses.

- 14,260 new learners accessed CALP e-learning courses in 2022, of whom 42% identified themselves as national staff.

As of 2023, CALP has seen the demand for face-to-face training return to similar rates as before the pandemic and more and more CWGs and external organizations are rolling out CALP courses or similar cash training. This demand complements e-learning and online courses.

Training needs have been discussed at many points in this report, with priorities identified including:

- People-centred responses: Numerous organizations have made investments in technical expertise in recent years, recruiting inclusion and accountability specialists to support mainstreaming across CVA (and other) programmes, as well as investing in partnerships with specialist organizations and related training and guidance. While embedding in-house technical expertise can be beneficial, key informants highlighted the need for all organizations – national and international – to understand the fundamentals of people-centred CVA and called for more efforts to make expertise publicly available so all agencies can make the necessary organizational shifts. Key informants also expressed concern as to whether cash actors have the expertise to understand and act on differentiated needs and constraints, highlighting that to transform practices there is need to go beyond ad hoc training and guidance by more firmly embedding expertise in day-to-day work (see Chapter 1 on People-centred CVA).

- Locally-led response: An overall mindset-shift is needed to consider ‘local first’ wherever feasible. There is a general need to ensure access of local actors to training opportunities provided for others, including for programme design, implementation and leadership in CVA coordination architecture – accessing both general CVA development opportunities (see Chapter 3 on Locally-led response) and specifics detailed in this chapter.

- Cash coordination: Key informants highlighted training on the cash coordination model as a need for cash coordination actors and other stakeholders, including cluster coordinators, to ensure its successful roll out (see Chapter 4 on Cash coordination).

- Linkages with social protection: Twenty-six percent (26%) of survey respondents identified the limited technical capacity of humanitarian staff as a key challenge in linking humanitarian CVA with national social protection systems and programmes. Conversely, 22% identified limited technical capacity of social protection staff as a key challenge to engage with humanitarian response. Training needs in this area are discussed further in Chapter 6.

- Data and digitalization: Forty-three percent (43%) of respondents perceived that ‘an understanding of data responsibility not being effectively mainstreamed across teams implementing CVA’ as one of the biggest challenges for improving the management of recipient CVA data, and 25% of respondents identified limited legal and compliance/due diligence capacity as one of the biggest challenges. The need to increase capacities around data management and digitalization, including addressing issues of cyber security, is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

- MPC and sector-specific CVA: Thirty-three percent (33%) of the survey respondents identified limited staff capacity as one of the biggest challenges to increasing the use of MPC (see Chapter 8 on CVA design).

- Climate and the environment: As an emerging area of interest, there is a general concern about additional skill sets and capacities needed regarding CVA across different aspects of climate mitigation and adaption as a new and developing area of interest (see Chapter 9).

Tools and guidance continue to be developed

Since the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report, a plethora of newly developed standards, tools and guidance have been produced on a diverse range of CVA-related issues. Actively using best practice is a key part of being able to achieve CVA goals in terms of scale and quality. Strikingly, 34% of the survey respondents perceived that lack of staff capacity was one of the biggest issues they faced in applying common standards, tools, and guidance. The other issues identified included that organizations preferred to use their own tools and guidance (42%) and a lack of commonly agreed standards for CVA (39%).

“80% of country offices now specify in their emergency preparedness and response plans that they would want to respond in cash if there is a shock. We have been working with each country office to help develop capacities. We now, in 2023, have new guidelines and a toolkit – ’CVA in Emergencies’, with a large component on preparedness. We are using CALP e-learning and the Programme Quality Toolbox.” Action Against Hunger.

The CALP Programme Quality Toolbox brings together, through a joint review, the best available CVA guidance, with content curated based on quality irrespective of which agency produced it. In 2023, CALP undertook a review of guidance and tools produced since 2020, which found very few new resources directly related to preparedness and none that were deemed superior to existing content. The Toolbox is widely used, especially by INGOs, and for some, such as CARE,32 has been a starting point to develop their own, tailored toolbox to increase their CVA preparedness.

Box 5.6: CALP Programme Quality Toolbox

Preparedness is one of eight sections and is sub-divided into three standards – organizational, programmatic and partnership preparedness.

The organizational standard emphasizes the importance of contingency or preparedness plans including consideration of CVA. It focuses on assessing organizational capacity and investing in systems, procedures and human resources to ensure quality programming. It refers users to CALP’s Organizational Cash Readiness Tool, as well as various preparedness-related tools from IFRC’s Cash in Emergencies Toolkit (CiE).

The programmatic standard includes actions on CVA feasibility and risk, analyzing and monitoring important markets and mapping existing social protection programmes. Related resources stem from both UN Agencies and the RCRCM Cash in Emergencies Toolkit, as well as the CALP Network and Oxford Policy Management’s Shock-Responsive Social Protection Systems Toolkit.

The partnership standard provides actions related to partnering with both FSPs and implementing partners, again comprised principally of CALP’s own and CiE Toolkit resources.

Implications for the future: Areas for strategic debate and priority actions

Areas for strategic debate

Our analysis highlighted the following considerations to inform further thinking and progress in this area.

- Given that the humanitarian system and context are changing, what should the priorities be for CVA preparedness and capacity development and who should have access to these opportunities? Findings from this report show that CVA skills and experience are increasing, but it also shows that preparedness and capacity across the system is uneven and that specific capacity gaps are emerging, some reflecting changing needs in the system. The need for increased investment in locally-led response is generally acknowledged but progress is slow, both in terms of direct funding by international donors and in terms of financing through partner agreements. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement efforts provide a good example of change, with commitments made and sustained investments resulting in an increasing percentage of national societies being ‘cash ready’. The evolution of CVA and changes in the external environment have created new preparedness and capacity needs, and elevated existing ones. Strategic investments are needed to address gaps in relation to data and digitalization, as well as to ensure opportunities related to expanding the use of MPC and strengthening linkages between CVA and social protection can be achieved.

- Will the new cash coordination model improve CVA preparedness and capacity? With the establishment of the cash coordination model and the global leadership role of OCHA and UNHCR in the coordination of CVA established, there is an opportunity to formally and systematically embed CVA preparedness in humanitarian system planning. The cash coordination model should enable more predictable funding for preparedness within existing funding levels. A key challenge will be coordinating CVA preparedness efforts at individual, organizational and system level. There will also be a need to consider CVA preparedness with development actors. However, there are concerns that progress with the coordination model (see Chapter 4 on Cash coordination) is slow and that without the promised additional resourcing, change will not happen.

- How should decisions be made about the balance of investment between preparedness for in-kind assistance and CVA, given that CVA is the modality of choice for most people affected by crises? There would appear to be a tension between policy commitments to put people affected by crises first, including their choice of humanitarian assistance and other policy and operational concerns.

Priority actions

In relation to the strategic debates above and other key findings in this chapter, the following are recommended as priority actions for stakeholders.

- Donors and senior leaders should seize opportunities to engage with strategic discussions around funding and innovative financing to increase investment in system level CVA preparedness and capacity. This includes linkages between humanitarian and development action.

- Donors should require, and track, that international organizations they fund provide onward funding to their partners to enable institutional preparedness and capacity development. They should also consider dedicated financing to address: (a) the preparedness and capacity needs of local actors overall; and (b) the critical capacity identified in this report.

- The CAG and CWGs should foster coherent approaches to CVA preparedness and capacity. Opportunities within the HRPs should be harnessed and linkages with social protection advanced as part of preparedness (see Chapter 6 on Linkages with social protection).

- Donors, implementing agencies and researchers should continue to generate learning and good practice on the use of CVA in contexts of economic volatility, including the impacts on recipients, markets and programming. They should do so in reference to the steps that donors, agencies and CWGs can take to prepare for, mitigate and manage these impacts.

- Communities of practice on CVA preparedness and capacity should be established at country, regional and global level to share and learn, identify strategic gaps, and progress collaborative initiatives. This could include engaging with coaching and mentoring exchange programmes being rolled out in the humanitarian sector to contribute to enabling mindset shifts around issues such as localization.

- All actors should advocate for predictable, multi-year resources for preparedness and capacity strengthening and exchange, with a particular focus on strategically important preparedness and capacity gaps. Funding predictability would allow for better, more sustained capacity strengthening and preparedness efforts. It should include direct resource allocation to local actors focusing on building their autonomy and organizational strengths. Actors that receive funding for preparedness should ensure the benefits of this funding are offered to their partners and other interested actors. Resources developed, wherever possible, should be made open source.

- Donors should collectively support CVA preparedness efforts as these will be vital to continued scale and effectiveness of CVA. They should fund local actors directly wherever possible and make it a requirement for organizations that they fund directly for preparedness activities to pass on the benefits of this funding to their partners.

3. See Kamstra, J (2017) Dialogue and Dissent Theory of Change 2.0: supporting civil society’s political role. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands.

4. Cabot Venton and Pongracz (2021). And, SPACE Framework for shifting bilateral progammes to local actors.

5. Also noted in recent consultations on training and capacity building carried out by CALP. CALP (2023) Consultation Process with Local Actors to Develop CALP’s Learning and Training Strategy In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), West and Central Africa (WCAF) and East and Southern Africa (ESAF) Regions. Consultation Report. CALP

6. For example, as noted in ALNAP’s State of the Humanitarian System (2022), based on a ‘small sample of agencies and countries … on average, UN staff were paid more than double their INGO peers, and staff of international organizations as a whole were paid on average six times the salary of L/NNGO staffers …. Although international organizations need to consider pay parity across their global operations, the impact of these pay differentials are very real for local job markets, perceptions of aid workers and staff retention in local organizations.

7. Cabot Venton (2021); Lawson-McDowall and McCormack (2021); Smith (2021); Bastagli, F. and Lowe, C. (2021) Social Protection Response to Covid-19 and Beyond: Emerging Evidence and Learning for Future Crises. Working Paper 614. ODI; Development Initiatives (2022) Overhead Cost Allocation in the Humanitarian Sector: Research Report. Development Initiatives; Development Initiatives (2023) Donor Approaches to Overheads for Local and National Partners. Discussion Paper. Development Initiatives.

8. IASC (2022) IASC Guidance on the Provision of Overheads to Local and National Partners. IASC.

9. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023) independent.

11. WFP Cash-Social Protection COVID-19 Cell/Coordination Group, 2022

12. UNHCR (2022) UNHCR Policy: Cash- based Interventions (2022–2026). page 5.

14. Smith, G. (2021) Grand Bargain Sub-Group on Linking Humanitarian Cash and Social Protection: Reflections on Member’s Activities in the Response to COVID-19. A report commissioned through Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC).

16.

CALP (2021) Good Practice Review on Cash Assistance in Contexts of High Inflation and Depreciation.

https://www.calpnetwork.org/publication/good-practice-review-on-cash-assistance-in-contextsof-high-inflation-and-depreciation/

17.

CALP (2021) Good Practice Review on Cash Assistance in Contexts of High Inflation and Depreciation.

https://www.calpnetwork.org/publication/good-practice-review-on-cash-assistance-in-contextsof-high-inflation-and-depreciation/

18. DG ECHO (2021) DG ECHO Guidance Note: Disaster preparedness.

19. DG ECHO (2022) DG ECHO Thematic Policy Document No. 3: Cash transfers.

20. UNHCR (2022) UNHCR Policy: Cash-based interventions (2022–2026).

24. CAG (2023) Global Cash Working Group Co-Chair ToR. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/global-cash-advisory-group/cashworking- group-cwg-co-chair-terms-reference-tor-global-cash-advisory-group-gcag

25. UNOCHA (n.d) This is UNOCHA. page 7.

26. Ibid.

27. OCHA/CashCap (2020) OCHA Internal Guidance – Cash in HRPs

28. Kriegler, C. and Rieger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance: Opportunities, barriers and dilemmas.

29. IASC (2023) The Grand Bargain Annual Independent Report. page 13.

31. IASC (2023) The Grand Bargain Annual Independent Report. page 13.

32. IFRC (2021) Strengthening Locally Led Humanitarian Action through Cash Preparedness. IFRC; IFRC (2021) Dignity in Action: Key data and learning on cash and voucher assistance from across the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement. IFRC