The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Chapter 8: CVA Design

Summary

Key findings

Multi-purpose cash (MPC)

- The use of MPC has increased but not to the extent anticipated.

- The lack of multisectoral needs assessments and response analysis is still seen as the largest barrier to increasing MPC.

- Concerns remain regarding the extent to which MPC will achieve sector-specific outcomes.

- The limitations of standardized transfer values are increasingly recognized.

- Technical processes can hinder rather than support people-centred CVA.

Sector-specific

- Consideration of CVA has increased across all sectors.

- 17% of survey respondents perceive sectoral outcomes not being achieved as a significant risk when using CVA, down from 33% in 2020.

- The availability of sectoral evidence, guidance, toolkits, and capacity development materials has increased.

- The lack of sector-disaggregated CVA data is a barrier to quantifying progress and encouraging uptake.

- Modality choices are unduly influenced by habits, perceptions, organizational inertia and donor preferences.

Complementary programming and cash plus

- Debates about terms, concepts and the operational implications of cash plus, complementary programming and integrated programming continue.

- Complementary programming is not being systematically adopted

- The relevance of Cash plus is well documented in the social protection sphere, offering learning opportunities for humanitarians.

Financial inclusion

- User-centred design is needed if CVA is to help achieve genuine financial inclusion.

- Discussion of financial inclusion and CVA focuses on formal structures, a wider view is needed to embrace informal structures.

- Collective efforts are needed to overcome barriers to financial inclusion.

Strategic debates

- Can a more effective relationship between sectoral programming and MPC be developed?

- How should technical priorities be balanced with recipient preferences when designing complementary interventions?

- Can CVA be designed to facilitate financial inclusion?

Priority actions

- Humanitarian actors, including operational agencies, CWGs and clusters, should systematically track sectoral CVA and MPC, to enable more effective understanding of the assistance provided and the relative impacts.

- Operational agencies, CWGs and clusters should engage in multisectoral assessment and analysis processes to facilitate the uptake of MPC and sectoral CVA.

- Sectoral stakeholders should increase cross-sectoral learning to overcome barriers to the uptake of CVA.

- CWGs and clusters should use MEB processes to facilitate understanding between sectors and cash actors, while avoiding unduly technical, time-consuming and costly processes that risk not supporting people-centred CVA.

- Humanitarian actors should use jointly developed metrics and tools for monitoring and evaluating the impacts of MPC and sector-specific CVA.

- CWGs, donors, and relevant intersectoral and sectoral representatives should jointly agree on guidelines on the relationships between MPC and sector-specific CVA.

- Humanitarian actors should assess and document the effectiveness of complementary programming.

- Humanitarian actors should incorporate feasibility analysis for financial inclusion into CVA design.

Interventions using cash and/or vouchers are generally categorized as either multi-purpose cash assistance (MPC) – often to address ‘basic needs’1– or sector-specific. This distinction both reflects and challenges the current international humanitarian architecture. Indeed, the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report highlighted cash as ‘a form of assistance whose use and outcomes are determined by users … (within) a sector-based system which organizes assistance by its intended purpose’2.

This chapter examines progress, opportunities and challenges relating to the intended outcomes of CVA, and associated intervention designs, response planning, funding, and coordination. This includes the use of and interrelationships between MPC and sectoral CVA, minimum expenditure baskets (MEBs), assessments and response analysis, transfer values, and complementary programming. The chapter also outlines trends and related evidence in respect of the potential of CVA as a pathway to financial inclusion.

Multi-purpose Cash

“Multi-purpose Cash Assistance (MPC or MPCA) comprises transfers (either periodic or one-off) corresponding to the amount of money required to cover, fully or partially, a household’s basic and/or recovery needs that can be monetized and purchased. Cash transfers are ‘multi-purpose’ if explicitly designed to address multiple needs, with the transfer value calculated accordingly. The extent to which a cash transfer enables basic needs to be met depends on the sufficiency of the transfer value and should be considered when terms are applied to specific interventions. MPC transfer values are often indexed to expenditure gaps based on a minimum expenditure basket (MEB)”, or other monetized calculation of the amount required to cover basic needs.

(CALP 2023 Glossary Definition)

MPC is frequently central to CVA discussions. As an unrestricted and intentionally multi-purpose form of assistance, MPC is often seen to facilitate greater choice and dignity for crisis-affected people. Stretching back to the Grand Bargain in 2016, much of the emphasis in policy to increase CVA has focused on MPC.

“One of the issues for me is that the reporting on MPC is not always very clear. I think this is something that the CAG is/should work on. Reporting varies by country and this is confusing.” (Focus Group Participant)

The limitations on tracking CVA and other modalities in general (see Chapter 2 on Volume and growth) means that data does not exist to provide an accurate, consolidated picture of the growth of MPC over time. Differences across responses in terms of how it has been planned for, and which coordinating body is responsible for tracking its use has further challenged quantification. Although the new cash coordination model outlines the responsibilities of cash working groups (CWGs) on integrating MPC into response plans and processes (see Chapter 4 on Cash coordination), there is less clarity about tracking and reporting, including the respective responsibilities of CWGs and clusters. A focus group participant noted that reporting on MPC is confusing due to country variations and recommended that the global Cash Advisory Group (CAG) work on this issue.

Although comprehensive, quantitative data is lacking. Analysis of Humanitarian Response Plans (HRP) and Financial Tracking Service (FTS) data gives some indications on the use of MPC. There is now a dedicated (albeit optional) MPC section in HRPs, which was used in 80% of HRPs in 2021 to explain whether or not MPC would be used, and why. However, the average number of plans with separate response requirements for MPC has remained at five per year over the last five years3. While data is incomplete, analysis shows that MPC made up 4.1% of total financial requirements in 2022 for FTS-tracked response plans, compared to less than 1% in previous years4. This growth is attributable almost entirely to the large MPC requirement for the Ukraine response, where it represented 25% of total funding of the HRP in 20225. By comparison, in Yemen (another large HRP) – despite some increase – MPC only accounted for 3.3% of the total HRP in 20226 . Such differences illustrate the wide variations in the use of MPC in different contexts, reflecting variations in the use of CVA in general (MPC and sectoral CVA) across different responses (see Graph 8.1 for an illustration of this based on response planning data).

Although comprehensive, quantitative data is lacking. Analysis of Humanitarian Response Plans (HRP) and Financial Tracking Service (FTS) data gives some indications on the use of MPC. There is now a dedicated (albeit optional) MPC section in HRPs, which was used in 80% of HRPs in 2021 to explain whether or not MPC would be used, and why. However, the average number of plans with separate response requirements for MPC has remained at five per year over the last five years3. While data is incomplete, analysis shows that MPC made up 4.1% of total financial requirements in 2022 for FTS-tracked response plans, compared to less than 1% in previous years4. This growth is attributable almost entirely to the large MPC requirement for the Ukraine response, where it represented 25% of total funding of the HRP in 20225. By comparison, in Yemen (another large HRP) – despite some increase – MPC only accounted for 3.3% of the total HRP in 20226 . Such differences illustrate the wide variations in the use of MPC in different contexts, reflecting variations in the use of CVA in general (MPC and sectoral CVA) across different responses (see Graph 8.1 for an illustration of this based on response planning data).

Graph 8.1: Response requirements for CVA (MPC and sectoral) for the 10 largest response plans with available data, 2022

Research suggests that volumes of MPC have increased in line with the growth of CVA overall, but ‘the shift towards MPC has not occurred to the extent anticipated’7. Survey respondents perceived the lack of systematic multisectoral needs assessments and response analysis as the largest barrier to increasing MPC, a response that was consistent across all respondent job profiles and regions (see Graph 8.2). This is consistent with other research, with issues related to the lack of multisectoral needs assessment and response analysis identified not only as a barrier to MPC and CVA, but also as a barrier to quality humanitarian action more generally8. The need to address this issue featured among the recommendations of previous State of the World’s Cash reports9 , while the need to improve joint multisector needs assessments was highlighted in the Donor Cash Forum’s Joint Donor Statement10 and the Grand Bargain (GB).

While recommendations and commitments have been made, expectations of seeing ‘cash programmes planned on the basis of joint and impartial needs assessments … have only partially been fulfilled’ and highlight that to achieve this ‘would require a more systemic change in the way the humanitarian system operates11’. Some stakeholders anticipate that creating a formal space for cash coordination in the international humanitarian architecture – through the new cash coordination model – will help facilitate more systematic multisectoral assessments and analysis and support a corresponding increase in MPC (see Chapter 4 on Cash coordination). However, the cash coordination model is still at an early stage, and it is too soon to know what the impacts will be in practice.

Graph 8.2: The Biggest Challenges to Increasing the Use of Multi-Purpose Cash (MPC) Interventions

The 2022 independent review of the GB workstream to ‘Improve Joint and Impartial Needs Assessments’ highlights the potential of the new iteration of the Joint Intersectoral Analysis Framework (JIAF) (see Box 8.1). The JIAF is a tool for needs and context analysis, distinct both from multisectoral needs assessment (which might feed into it), and response analysis (which the JIAF can help inform). It aims to ‘bring together sectoral assessments and analysis to consider the full range of needs and how they relate to one another’, using an intersectoral approach that ‘helps identify priorities and supports the sequencing and articulation of interventions’12.

Box 8.1: The Joint Intersectoral Analysis Framework

- The JIAF 2.0 sets global standards for the analysis and estimation of humanitarian needs and protection risks. It provides:

Estimation of the overall magnitude of a crisis: How many people need humanitarian assistance and protection. - Estimation of intersectoral severity: How severe is the humanitarian situation that results from the compounding effect of overlapping sectoral needs.

- Estimation of sectoral needs in an interoperable and commonly understood way.

- Identification of linkages and overlaps between sectoral needs.

- Identification of those most affected.

- An explanation of the drivers: Why a crisis is happening and what is the underlying context.

Source: JIAF website https://www.jiaf.info/

Since sectoral processes and their results ‘constitute the building blocks of JIAF13’, concerns have been noted about how it will address cash both as a specific need expressed by affected populations and as a cross-cutting tool. In contrast, others feel that the joint approach to sectoral and intersectoral needs, and an emphasis on contextual factors (including markets and financial systems), are elements that can help ensure the incorporation of cash14. With JIAF 2.0 set to roll out in 2024, it will be worth monitoring the impacts in practice, including in tandem with the transition to the new cash coordination model.

The second, third and fourth largest barrier to MPC identified through the survey (Graph 8.2), were limited funding, limited organizational systems, and limited staff capacities. These barriers correspond with some of the most critical barriers to the uptake of CVA overall (see Chapter 2 on Volume and growth) and so addressing them is likely to contribute to the growth of MPC and CVA more generally. Perspectives about the greatest opportunities for growth vary; some argue that there is more potential to scale MPC than sectoral CVA as it is MPC that has faced more systematic challenges within sector-oriented response planning and implementation15; others argue the opposite (also see below on sector-specific CVA), and some argue growth opportunities are greater in other areas.

Survey respondents ranked lack of evidence of MPC’s effectiveness as the least significant barriers to increasing the use of MPC. This is supported by improvements in the availability of tools to capture and analyze the impacts of MPC. For example, evidence-based guidance and outcome indicators for MPC, developed through the Grand Bargain Cash Workstream, were published in 202216, along with a linked MPC monitoring, evaluation and learning toolkit17 (see Box 8.2). Further, the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement has been leading a pilot initiative to monitor and evaluate MPC impacts on well-being, using a people-centred methodology (see Chapter 1 on People-centred CVA), and organizations such as World Vision have developed their own CVA compendium of indicators18 to better track MPC and CVA overall.

Survey respondents considered evidence of the effectiveness of MPC a less significant barrier than some other factors, but concerns remain19 regarding the extent to which MPC will achieve sector-specific outcomes. Research suggests that questions about where accountability lies for achieving sectoral outcomes has the potential to impede the scale-up of MPC7. Further, some sector-focused key informants felt that reporting on the contribution of MPC to sectoral outcomes has not notably improved, with a lack of clarity in some contexts on how interventions are addressing sectoral needs (more on this below)21. One key informant remarked that significant increases in MPC might affect how outcomes for crisis-affected people are monitored and evidenced, particularly relative to sector-focused approaches and metrics for success.

Box 8.2: Collaborative development of standardized metrics and tools for monitoring MPC

The Grand Bargain Cash Workstream published the Multipurpose Cash Outcome Indicators and Guidance in 2022. It comprises a core set of both cross-sectoral and sectoral indicators, highlighting that both are relevant in terms of MPC outcomes. Multiple NGOs, UN agencies, donors and clusters contributed to its development. The guidance advises that indicator selection be informed by project design and objectives, ideally with a combination that is complementary and avoids duplications in data collected.

The cross-cutting, multisectoral indicators are largely focused on the perceptions and preferences of recipients, incorporating quantitative and qualitative elements. The development of the sectoral indicators was a multi-cluster, collaborative exercise, engaging cluster CVA focal points and working groups to lead the identification and validation of relevant indicators. This approach helped build greater mutual understanding between the ‘cash community’ and sector experts within the clusters22.

The guidance was further operationalized through the development, led by Save the Children, of the aligned Multipurpose Cash Assistance Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning Toolkit23. It includes KoBo survey and report templates and tools in multiple languages. Mercy Corps, Save the Children and the IRC have been piloting the tools, with plans for further rollout and training in 2024. The aim is for the toolkit to further contribute to documenting the effects of MPC.

Feedback from key informants highlighted several issues beyond those identified in the survey that can directly impact the uptake of MPC at response level, much of which plays out through the interrelations between MPC and sectoral cash. Although there are established definitions for MPC ( e.g., CALP glossary), key informants highlighted that differing understandings remain among both donors and practitioners, with sufficient grey space within the definitions to allow varying applications across different responses.

“Both donors and practitioners are confused about the different terminologies and modes of designing MPC. There are too many methodologies that are used for country-specific design of MPC and there is still a need for more coordination and more authorization of these different approaches.”

(Focus Group Participant)

Some of these issues relate to differing interpretations of the ‘basic needs’ that MPC can be designed to address, particularly whether MPC is cross-sectoral, or should be broken down and attributed to different sectors. For example, one key informant described regular discussions with sectoral colleagues within their organization with a focus on ‘MPC for what?’. At response level this can play out in struggles to define what is sectoral cash, and what is multi-purpose. Key informants gave the example of Ukraine, where there was clarity that sectoral cash should be designed as a top-up to MPC. However, in many responses the line between MPC and sectoral cash is blurred.

Combined, all these issues affect the uptake of MPC and continue to have operational impacts. For example, all key informants of a rapid study on the role of cash coordination in government-controlled areas of Syria during the 2023 earthquake response noted arguments from some sectoral stakeholders for MPC to be considered as sectoral transfers. This issue was referred to the HCT, and took a further two months to be resolved, leading to major delays in assistance provision, that undermined the cohesiveness of CVA coordination, and likely contributed to the Government of Syria’s reservations about the use of CVA24. On the other hand, analysis of cash coordination during the earthquake response in North-West Syria showed effective inter-cluster coordination between the Cash Working Group and sectors, including for example, harmonizing the value of ‘cash for winterization’ under the Shelter/NFI sector with the agreed one-off MPC transfer value25.

A lack of clarity on remits often contributes to tensions between MPC and sector-specific CVA. Concerns about the technical quality of interventions and achieving specific sectoral outcomes drive these tensions, and, critically, are often associated with questions around funding allocations and influence in response planning processes. These concerns reflect the broader perspective that the growth of MPC calls the current humanitarian coordination architecture into question, with the potential to reduce the role and power of clusters within it15.

Some stakeholders, worried about the implications for sectoral budgets, have pushed back back on the use of MPC, which is not new. It is based in part on concerns that reducing the volume of sector-specific transfers (CVA or in-kind) could also lead to a reduction in resources available for ‘softer’ programming components (e.g., behaviour change, capacity strengthening). These elements of a response are traditionally more challenging to fundraise for as they produce less tangible or immediate outputs but can be essential to achieving certain outcomes.

“Sectors that have monetised their in kind inputs have the most to lose from the transition to MPC.” (Independent consultant)

One key informant reported hearing increasing discussions on the merits of ‘going back to sector-specific cash’, particularly from sectors that had been considered more comfortable with MPC, including food security, shelter, and WASH. Much of this seems to hinge on issues related to role legitimacy and funding. A key informant also noted a trend towards organizations defining interventions as MPC, but only providing transfer values commensurate with the sections of the MEB that align with their sectoral mandates. This can be problematic if it precludes other organizations from addressing the assistance gap through efforts to avoid duplication of receipt of MPC and raises efficiency questions if more than one organization provides MPC payments to a recipient.

“Overall, it’s very positive that, knowing where we were even five years ago, we now get much more interest and acceptance of MPC from the sectors.” (Focus Group Participant)

On the other hand, key informants also highlighted progress made in sectors such as health to identify when and how to combine MPC with sectoral CVA and other modalities to better address diverse needs (see below on complementary programming). Key informants also reported increasing interest and acceptance from cluster coordinators on linking with MPC. This includes, for example, better understanding of how to contribute to sectoral components of the MEB and align with MPC as part of cluster strategic planning.

The distinction between MPC and sectoral cash assistance is of primary relevance from the perspective of implementing agencies, whereas from a recipient perspective all (unconditional) cash received is likely to be functionally ‘multi-purpose’. Similarly, research has shown that from a recipient standpoint, the primary determinant of the effectiveness of cash is its transfer value, whether for MPC or sectoral cash27.

Several key informants raised the importance of transfer values, usually relating to the growing recognition of the limitations of standardized transfer values that do not take account of diverse needs and household compositions. Key informants highlighted the need for tailoring transfer values to address specific needs, for example using approaches that allow unified/standard transfer values to be topped up with allocations for sectoral or other specific needs. This might include layering or sequencing MPC and sector-specific CVA, and/or potentially through a case management approach.

MEBs frequently play a central role in informing transfer value calculations. Collaborative MEB development processes can potentially provide a platform for more connections between sectoral cash and MPC and create synergies between programmes to maximize outcomes15.

However, these processes are also inherently technical, if not necessarily highly complex, in nature. In so being, they represent one example of the concern that excessive reliance on technical processes, not least those with such a singular, definitive outcome, may hinder rather than support more people-centred CVA. For example, one key informant noted that different sectors and organizations working with vulnerable groups with specific needs (such as people living with disabilities), often contest MEB processes because they tend to inform universal transfer value decisions that often prove insufficient for those with bespoke needs. Other key informants corroborated this, noting variously that ‘it helps to have a holistic view of need through the MEB, but then it does not always translate into a transfer value that is inclusive’ and ‘an MPC transfer kept at the value of the MEB will not be sufficient for some specific needs’.

The latest MEB Guide to Best Practice highlights the importance of determining how light or heavy an MEB process should be, considering the circumstance and intended use(s)29. In particular, the guidance draws attention to the need for a process that is designed to make evidence-based decisions on MEB design without being unduly technical, time-consuming or costly. It goes on to provide guidance on including peoples’ priorities into a MEB, bearing in mind that ‘it should ultimately be the affected populations themselves that define what is a priority need’. However, several key informants emphasized that the definition of an MEB should not preclude necessarily bespoke CVA transfer values, especially in protracted crises.

Several people also remarked that there is not enough collaboration between those working on MPC and sectoral CVA, and between those working on sectoral cash within different sectors. For example, health, WASH and nutrition practitioners highlighted missed opportunities to share good practices around analyzing barriers or challenges with balancing the flexibility of CVA and the imperative for quality. On the other hand, examples were shared from the last couple of years from Nigeria and Syria where the Nutrition Cluster has led positive and interesting coordination between themselves, the Food Security Cluster and the CWG. CALP’s convening of a twice-yearly forum for co-leads from the various cluster cash/cash and markets technical working groups and OCHA/CAG representatives was also noted as an attempt to enable more shared learning that could possibly be replicated at country level.

Sector-Specific CVA

Sector-specific CVA is one of two overarching categories for CVA programming. However, progress, challenges, and opportunities in respect of CVA often differ between sectors. Overall, there is clear evidence that the use of CVA could be increased if used appropriately22. Pursuing this will require that the relative investment in CVA and in-kind assistance continues to shift towards CVA. Thirty-nine percent (39%) of survey respondents perceived that sectoral CVA represents the largest opportunity to increase the use of CVA as a proportion of overall humanitarian funding. This potential was also identified in research focused on increasing the use of CVA, as well as the latest CVA Tracking Report31.

Sector-specific CVA is one of two overarching categories for CVA programming. However, progress, challenges, and opportunities in respect of CVA often differ between sectors. Overall, there is clear evidence that the use of CVA could be increased if used appropriately22. Pursuing this will require that the relative investment in CVA and in-kind assistance continues to shift towards CVA. Thirty-nine percent (39%) of survey respondents perceived that sectoral CVA represents the largest opportunity to increase the use of CVA as a proportion of overall humanitarian funding. This potential was also identified in research focused on increasing the use of CVA, as well as the latest CVA Tracking Report31.

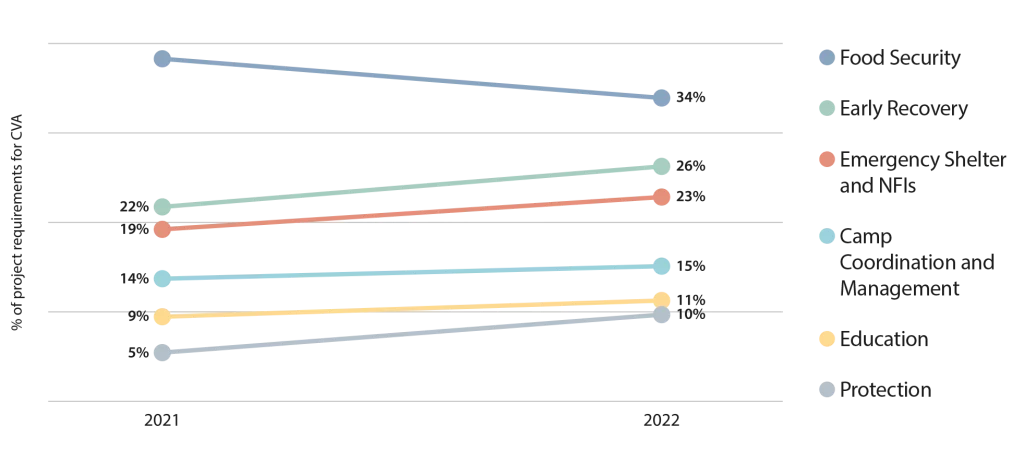

A focus group discussion with representatives from the Global Education, Food Security, Health, Protection, Nutrition and Shelter Clusters, as well as various key informant interviews, revealed an increased appetite for the routine consideration of CVA as a modality across all sectors, when contextually appropriate32. A review of 18 HRPs corroborated this; it showed an increased use, between 2021 and 2022, of CVA as a share of overall activity funding by the Early Recovery, Shelter and NFIs, Education, Protection, and CCCM Clusters (see Graph 8.3 – note this only covers sectors where CVA represents a minimum 10% of HRP requirements)33. Although CVA decreased as a percentage of planned activities in the food security sector, this was largely due to changes in the Sudan context, including a military coup, which led to a significant reduction in CVA due to donor concerns. Excluding Sudan, the aggregate percentage of CVA for food security across the other 17 HRPs also increased slightly from 2021 to 202233.

Graph 8.3: CVA as a percentage of sectoral activities for sectors where CVA represents 10% or more of HRP requirements

- Key informants suggested that the shift towards CVA as a modality during the COVID-19 pandemic and the work on the new cash coordination model likely reinforced, if not altogether drove, these trends. In addition, efforts by such sectors as shelter and WASH to enable the pursuit of Market-Based Programming (MBP), especially through the development of related guidance, are commonly perceived to have contributed positively to CVA uptake in those sectors.

Since 2020, there have been multiple sector-specific research initiatives, culminating in a growing evidence base for the use of CVA for sectoral outcomes. This has gone some way towards filling the evidence gap noted in the State of the World’s Cash reports in both 2018 and 2020 and is perhaps linked to the diminished concerns related to CVA uptake, most notably that sectoral outcomes will not be effectively achieved by using CVA. Indeed, only 17% of survey respondents perceived this to be one of the biggest risks associated with CVA, compared to 33% in 2020. However, such concerns are more acute in respect of MPC (as seen in the section above) which some sectoral practitioners perceive as being at odds with their ability to achieve sectoral outcomes.

Since 2020, there have been multiple sector-specific research initiatives, culminating in a growing evidence base for the use of CVA for sectoral outcomes. This has gone some way towards filling the evidence gap noted in the State of the World’s Cash reports in both 2018 and 2020 and is perhaps linked to the diminished concerns related to CVA uptake, most notably that sectoral outcomes will not be effectively achieved by using CVA. Indeed, only 17% of survey respondents perceived this to be one of the biggest risks associated with CVA, compared to 33% in 2020. However, such concerns are more acute in respect of MPC (as seen in the section above) which some sectoral practitioners perceive as being at odds with their ability to achieve sectoral outcomes.

The growing evidence base has informed the development of guidance, toolkits, and capacity development materials by various Clusters and individual agencies. In particular, the education, food security, nutrition, protection and WASH sectors have produced or updated toolkits and conducted specific capacity-building initiatives to support Cluster Coordinators in navigating the added complexity of facilitating CVA uptake.

Within specific sectors, positive indicators with respect to the uptake of CVA include: - The Global Nutrition Cluster reconvened its CVA-related Technical Working Group, and included, among its primary objectives, a mapping of all relevant initiatives, challenges and promising practices.

- The Global Protection Cluster, specifically its Task Team on Cash for Protection, established a centralized mechanism for tracking usage of CVA for Protection outcomes across its constituency.

- Key informant interviews with health practitioners suggested that the use of CVA is increasingly considered a “low hanging fruit” when it comes to covering transportation costs to health facilities, especially for people with chronic illness, and can play a key role in improving access to and use of health services35Case studies in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso and Jordan available here.

- In 2023, the Global Food Security Cluster published a review on the use of cash transfers in contexts of acute food insecurity, with the express intent of encouraging the scale up of cash, and promoted better programme design and more consistent modality choice36.

“Seed quality is defined differently by different actors. A challenge with using cash for seeds is addressing concerns regarding seed quality … Vouchers and in-kind are often the default modality when distributing seeds; cash is still not used very much. We wanted to explore how using cash for seeds could empower more farmers, and support both the formal and informal seeds sectors.” (CRS)

There are also numerous examples of the evolving use of sector-specific CVA. For example, key informants highlighted that cash can play a vital role as part of a holistic response to preventing or responding to Gender-Based Violence (GBV), especially when informed by appropriate response analysis. This has prompted discussions on the optimal duration of CVA and the need to balance the pursuit of scale and cost-efficiency with the need for a case-based approach to respond to the unique protection risks and related assistance needs of highly vulnerable individuals.

Another example of evolving sector-specific CVA is the work of Catholic Relief Services (CRS) which has been building evidence to make the case for CVA for seeds in support of agriculture-based livelihood outcomes. CRS published a Rapid Seed System Security Assessment (RSSSA) Toolkit in 2023, which highlights cash and vouchers as potential short-term responses to support poor or vulnerable farmers to access seed in both formal and informal markets37.

At agency level, at least one INGO has placed CVA advisors with specific sector focus in their technical advisory teams to build awareness among sectoral experts of appropriate CVA use cases. Other organizations have maintained or established internal CVA communities of practice or equivalent, including discussions on promoting the uptake of sector-specific CVA. Organizations, such as NRC, have also continued efforts to actively promote the use of CVA across ‘core competencies’, requiring those in charge of programme design to shift the ‘burden of proof’ towards in-kind, away from CVA. While not a new phenomenon, this remains a common approach across agencies, in part to overcome the fact that CVA uptake often stems from a single sector and needs to be mainstreamed or ‘pushed’ in other sectors.

“The lack of comprehensive global data on sectoral CVA makes it difficult to evidence the scale of progress.”

(CALP – Increasing the Use of Humanitarian CVA)

Despite the progress and good practices outlined above, an array of barriers continues to inhibit the increased use of CVA among the sectors. Research shows that the limited amount of sector-disaggregated CVA data is a barrier to further quantifying and encouraging uptake, a fact also reflected in other research on tracking CVA38. As a consequence, there is often a lack of clarity on whether the use of CVA has increased in absolute or relative terms – including by some sector cash specialists.

Recent research, supported by key informants’ feedback, shows that, despite mounting evidence on the achievement of sectoral outcomes with CVA and the growing use of MPC to meet basic needs, individual habits, perceived complexity of ‘new’ approaches, organizational inertia and donor preferences (either real or perceived) unduly influence sector-specific modality choices. This inertia to change is widely evident, even in the food security sector, where the ‘burden of proof’ has been shifting in favour of CVA for some time. As a result, the default modality still often leans towards in-kind, at both organizational and (in some cases) at response level, despite the widely recognized flaws of arbitrary deference to in-kind.

While inertia inhibits progress in many cases, there are many important concerns that have limited the use of CVA in some sectoral contexts. For example, the global Food Security Cluster’s recent report on CVA in contexts of acute food insecurity concluded that, despite progress and the relative prevalence of CVA in the sector, it is still falling short of its potential39 . While drawing attention to how individual habits, past modality choices and funding streams earmarked to in-kind delivery have impacted modality decision-making, it also highlights examples of governments restricting the use of cash for food security in areas where they have limited control and where there is a high presence of non-state armed groups. Some responses from key informants, supported this, noting that contextual barriers to CVA, including government action, can impact modality decisions. Further, it seems, the use of cash is still perceived as more technically complex and exposed to greater risk, including the challenges of reporting on contractually agreed food security sectoral outcomes39.

“Organizations engaging in cash for health need to work closely with the Ministry of Health, health insurance funds and other existing output based contracting systems with health service provider payment mechanisms, but also more traditional FSPs’. This type of engagement for the purpose of large-scale reimbursement mechanisms for direct and indirect medical costs to providers and/or patients is new for many organizations.”

(WHO)

Key informants noted that CVA counterparts often lack sufficient awareness of sector-specific dilemmas regarding the use of CVA. For example, a health practitioner emphasized that a lack of systematic analysis of the barriers to quality healthcare still hamper the wider use of cash to meet health needs. Identifying these barriers (e.g. financial, physical, social) was considered paramount to designing integrated programmes, inclusive of CVA as relevant, to overcome them effectively. The same key informant explained that the range of stakeholders that need to be engaged to design CVA for health was another consistent barrier to CVA uptake. Added to this were concerns on maintaining quality of healthcare, incentivizing self-medication, providing ‘one-size-fits-all’ assistance and, more broadly, the commodification of primary healthcare. Aligned with this is the perspective that reimbursing service providers directly, rather than making payments to households to pay for medical services, can be a more effective means to promote access to quality healthcare. The potential to use CVA for households in tandem with system strengthening interventions to enable access and support the provision of improved services in sectors such as health and education was also highlighted. The objective here would be collaboration with relevant national/government service providers to support sustainability and avoid creating parallel services.

Key informants with a protection sector focus highlighted that definitional, technical, and analytical barriers inhibit the uptake of sector-specific CVA. They explained how confusion between the use of MPC for individuals targeted due to protection risks and cash provided for Individual Protection Assistance (IPA) hindered broader uptake. As with the health sector, key informants also pointed to the challenges of capturing protection-related costs within MEBs.

Despite, or indeed because of these barriers, several opportunities have been identified to increase the uptake of sector-specific CVA. One key informant noted the opportunity of adopting a ‘can do’ attitude and expanding pilots of sector-specific CVA, helping address the perceived or actual lack of evidence supporting effectiveness. Despite the relative proliferation of evidence and guidance outlined above, key informants perceived that more can always be done, either in developing new resources or ensuring existing resources were more broadly accessible, for example, through translation or capacity-strengthening initiatives.

Box 8.3: Opportunities for increasing CVA in specific sectors

Key informant interviews and focus group discussions suggest that opportunities for increasing CVA in specific sectors include:

- The Global Education Cluster leveraging funding to fulfil its objective of supporting more countries and partners to integrate cash in education programming. It plans to track funding for education in

emergencies which should, at least in part, help address the current lack of data on the use of CVA in education related programming. - The potential to increase the use of vouchers to replace in-kind provision of inputs, where internal ‘quality assurance’ concerns generate reluctance to use cash. Key informants recognized though that this was not necessarily optimal or best practice and could limit positive effects for local, especially informal, markets.

- More research, such as work the Global Shelter Cluster are undertaking to understand what informs the decision to provide cash assistance for shelter outcomes, given that there is currently no single, uniform response analysis process for the sector.

- Systematic engagement with Global Health Cluster Coordinators on the topic of CVA and exchanging with counterparts from other sectors, notably WASH and Nutrition, to overcome shared challenges to using sector-specific CVA. The Global Health Cluster also highlighted the need to conduct a barriers analysis on accessing health services, in addition to the usual supply side (quantity and quality) analysis, to inform programme design and modality selection. Other implementing agencies will likely benefit from UNICEF’s recent paper series on Cash and Health, which sets out how CVA can contribute towards health outcomes and usefully presents seven considerations on setting up Cash for Health interventions41.

While acknowledging these opportunities, and in contrast to survey findings, some key informants perceived that there was far greater potential to increase CVA relative to in-kind assistance, in both absolute and relative terms, by focusing efforts on expanding MPC rather than sector-specific CVA. At the same time, most recognized the limitations of an undue prioritization of scaling MPC and the need to focus on the effective achievement of outcomes for crisis-affected people, informed by balanced consideration of both the potential and the limitations of CVA.

Complementary Programming and Cash Plus

Concepts and practices related to complementary programming have continued to gather momentum in recent years. This is driven primarily by the imperative to more efficiently and effectively respond to the diverse realities of crisis-affected people and the increasing recognition of the relevance of holistic approaches in doing so.

“Complementary programming is the combined use of multiple modalities and/or activities to address needs and achieve a specific outcome or outcomes for a given target group of aid recipients. Complementary interventions can be implemented by one organization or multiple organizations working collaboratively. It can include both incorporating multiple modalities or activities within one project or programme, and/or linking the target population to assistance provided by other sectors or organizations. This approach is premised on the evidence that programmes are more effective where they incorporate the different factors contributing towards achieving outcomes and addressing needs. Ideally this will be facilitated by a coordinated, multisectoral approach to needs assessment and response analysis.”

(CALP Glossary 2023)

Within humanitarian CVA and social protection, complementary programming incorporating cash is often framed and termed as ‘cash plus’. However, there are ongoing debates about the terms and concepts of cash plus, complementary programming and integrated programming (for definitions, see CALP Glossary 2023), as well as differing interpretations of the operational implications. A key concern regarding the term ‘cash plus’ is that it suggests the centrality of cash, rather than considering the full array of activities that may be needed to achieve an objective and so risks overlooking their relative utility. Further, some feel the use of the term risks implying that historically cash programmes have not considered complementary activities’ which is not the case. World Vision International, for example, do not use the term ‘cash plus’ as it is seen to undermine efforts towards cross-sector programmatic integration with CVA as an enabler to various outcomes, often alongside other activities. Other actors, such as ECHO and NRC, refer more generally to complementary interventions and companion programming, respectively. In this report terms are used in line with the CALP Glossary (2023).

“A starting point is to ask people what their priorities are, and what can’t be met by cash for basic needs. This would turn it on its head. Multi-purpose is your default cash pillar, and then you have other layers of assistance and services around it. This is what’s needed for agency and recovery. It’s also conducive to the nexus, linking to longer-term solutions.”

(Ground Truth Solutions)

Several key informants raised that cash assistance, typically MPC, can represent a foundation allowing recipients to meet their basic needs, which can then be layered or sequenced with complementary interventions and services – e.g., livelihoods technical support or health service access. This view is also seen in ECHO’s Thematic Policy on Cash42among others. The approach recognizes the limitations of humanitarian cash, or indeed any other singular approach, in meeting diverse and evolving needs. Furthermore, some argue that complementary programming, including the use of CVA, could be one way to operationalize the humanitarian-development nexus, as well as provide an effective exit strategy for humanitarian agencies, especially in protracted crises.

The CAMEALEON Consortium in Lebanon’s 2022 study43usefully distinguished different ‘cash plus’ approaches44. It highlighted that it can be planned during the design stage, by designing programmes that focus primarily on distributing CVA, in whatever form, whilst also involving complementary non-CVA components. The research also found that ‘cash plus’ can be reactive, linking CVA recipients with complementary activities or services once a programme is underway, via individual referrals or inter-cluster/sector coordination.

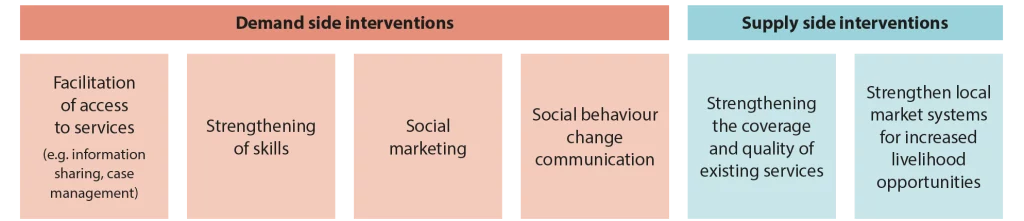

Graph 8.4: Examples of what the ‘plus’ could look like in interventions using MPC

Complementary programming can be designed to achieve one or more sector-specific and/or multisectoral outcomes, focused on responding to needs and risks, contributing towards addressing their root causes or seeking durable solutions for people affected by crisis. Programmes may, for example, be designed to lift non-financial, structural barriers faced by people in addressing their needs and mitigating risks that are beyond the scope or potential of CVA programmes that do not have complementary elements. Some stakeholders also conceptualize it in terms of its potential to contribute to longer-term self-reliance and resilience.

“Programme objectives and holistic design are what define whether root causes can or should be addressed. Let’s be realistic that humanitarian CVA to meet basic needs is not intended to nor provides enough to be gender or inclusion transformative on its own.” (Key Informant)

“One of the standards I’d like to introduce is that all cash programmes include complementary programming unless

there’s some reason they can’t. So, complementary by default.” (Mercy Corps)

Others go as far as to highlight its transformational potential, for example with respect to gender. For example, within food assistance interventions there is evidence to suggest a positive correlation between the combination of complementary modalities and the achievement of outcomes that can significantly improve women and girls’ well-being45 . To achieve gender responsive outcomes, UNICEF recommends being intentional in how both primary and complementary activities will sustainably contribute towards intended gender outcomes and to ensure the quality of the intervention46.

Certain organizations have adopted complementary cash programming as standard or default, thus ensuring that most, if not all, their cash programmes have complementary components. Others appear to be taking a case-by-case approach, determining whether complementary activities are necessary in a given response for the effective achievement of outcomes and designing programmes accordingly. Guidance in this area is increasing; CARE has identified 15 promising practices to maximize outcomes in complementary programming47 and UNICEF has defined eight criteria for ‘cash plus’ success48 (see Box 8.4). Key informants also mentioned that some agencies are adapting their monitoring tools to track the specific contributions made by complementary activities to the achievement of intended outcomes, via ‘cash plus’ or otherwise. In time, this should increase the evidence of the relative effectiveness of different forms and combinations of complementary programming incorporating CVA.

Box 8.4: Eight ‘cash plus’ criteria for success48

- Ensure political buy-in.

- Formalize agreement in between sectors on commitments to operationalize ‘cash plus’.

- Raise staff awareness about the design and the articulation between the ‘cash’ and the ‘plus’.

- Ensure the existence, accessibility and quality of the services delivered as the ‘plus’.

- Case management to enable linkages to services across sectors.

- ‘Plus’ components should be properly resourced.

- Demand-side interventions need to be matched with supply-side investments.

- ‘Cash plus’ components need to be rooted in a sound situation analysis.

Despite an increase in guidance and good practices, key informants indicated that complementary programming is not being systematically adopted. It seems limited evidence regarding complementary programming in fragile contexts and humanitarian response is part of the issue, with one study describing the evidence as ‘nascent’50.

The relevance of ‘cash plus’ approaches to maximize outcomes is already well documented within the social protection sphere, representing a significant opportunity for humanitarian practitioners. In particular, the effectiveness of complementing cash assistance with other activities as part of social safety net programmes is extensively evidenced across multiple contexts51. On a further positive note, in 2023, IDS concluded that the design of ‘cash plus’ in protracted crisis, with a focus on social assistance, is similar to that in more stable environments52. In addition, they reported positive outcomes of ‘cash plus’ programmes in the areas of income, food security and economic inclusion.

“A starting point is to ask people what their priorities are, and what can’t be met by cash for basic needs. This would turn it on its head. Multipurpose is your default cash pillar, and then you have other layers of assistance and services around it. This is what’s needed for agency and recovery. It’s also conducive to the nexus, linking to longer-term solutions.”

(Ground Truth Solutions)

As well as the need for further evidence-building, key informants noted the need to invest in referral mechanisms so that cash recipients can be more efficiently and effectively connected to other relevant service providers, be they from the development, private or public sectors. Key informants raised another possibility related to improving linkages between CVA programming and Case Management Systems. The principles of Do No Harm, in particular mitigating risks associated with data sharing, need to guide all such development.

There is some momentum towards complementary programming incorporating CVA, but some key informants stressed this should not detract from the fact that, recipients’ primary determinant of the effectiveness of cash assistance is its value. Thus, the need to carefully weigh the relative costs and benefits of additional activities.

Financial Inclusion – a golden thread?

In addition to enabling recipients to meet basic needs or achieve sector-specific objectives, CVA programming can contribute towards other beneficial outcomes for crisis-affected people, including as a potential pathway towards financial inclusion. Previous State of the World’s Cash Reports (2018 and 2020) identified the role of CVA in facilitating financial inclusion and empowerment as a topic of high interest, but one with a thin evidence base. The limited number of relevant studies referenced in those reports suggested that despite some positive impacts on access and use of financial services, there was little evidence of CVA in humanitarian contexts having led to financial inclusion per se, particularly for the poorest and most marginalized groups. Similarly, where opportunities did exist to contribute to financial inclusion, success would be dependent on programmes being intentionally designed for this purpose, in ways appropriate for each context.

“People are financially included when they have access to a full suite of quality financial services, provided at affordable prices, in a convenient manner, and with dignity. Financial services – transactions, payments, savings, credit, and insurance – are delivered by a range of providers, most of them private, and reach everyone who can use them, including

the disabled, poor, rural, and other excluded populations. Financial inclusion strives to remove the supply and demand side barriers that exclude people from participating in the financial sector and using these services to improve their lives.”

(CALP Glossary 2023)

In earlier State of the World’s Cash reports, discussion focused on a particular view of financial inclusion i.e., linked to formal structures such as traditional banking systems, mobile banking and so on. A wider view of financial inclusion embraces a much broader range of formal and informal structures – ranging from village savings and loans associations to large-scale micro-finance institutions.

Efforts to better understand and evidence if, how, and where CVA has supported financial inclusion have continued since the last report – though focus has been on inclusion in relation to formal financial services of certain types.

In some contexts, CVA may be people’s first engagement, or provide opportunities to increase engagement, with formal financial platforms and services. The value of financial inclusion for people who have experienced shocks or who are vulnerable to future hazards is often framed in terms of helping build resilience, through ‘a sustainable impact on income growth or asset accumulation’53 .

Graph 8.5: Mercy Corps’ Cash-2-Financial Inclusion Model (C2FI)

Research reflecting on the potential uses of digital financial platforms for refugees highlights that, ‘having a mobile money account is about more than just a way of receiving cash payments and a place to store funds, it also gives the user access to every-day financial services, like paying children’s school fees; paying for energy needs; receiving remittances from abroad; accessing savings, loans and more’54.

In 2021, GSMA and Mercy Corps co-authored a blog that concluded that ‘CVA programmes can provide a springboard to financial inclusion, but spotting the right opportunity, and good programme design, are key55. The Cash-2-Financial Inclusion (C2FI) matrix was developed as a simple, evidence-based framework to help understand which contexts offer the best pathways from CVA to financial inclusion, while recognizing that C2FI will not always be a suitable or viable option (see Graph 8.5). Potentially ‘high impact’ opportunities to use CVA as a catalyst for financial inclusion are identified as those with a strong enabling environment (e.g., stable context, mature markets) and a target population with requisite demand and capacity – for example, refugees in Uganda55.

The same research identifies Iraq as an example of a ‘demand driven’ context, where there is requisite client capacity and demand for financial inclusion, but where ‘deep mistrust in institutions (…) must be overcome to successfully deliver C2FI’55. A study analyzing the financial management practices and preferences of people in conflict-affected areas in Iraq demonstrated people’s preference for informal mechanisms for saving and borrowing money, with engagement with formal financial institutions affected by issues of (lack of) trust, accessibility, and suitability of the services offered. In this context, it was recommended that ‘community-based saving and borrowing schemes can be re-established and strengthened as a means of promoting good financial practices’58.

While financial inclusion tends to be defined in terms of access to formal financial institutions and services, informal and community-based mechanisms can play a key role, as the Iraq case above shows. In many contexts there are a wide range of institutions including cooperatives, Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLAs), savings and credit cooperatives, alongside larger entities such as micro-finance institutions. In some contexts, such structures may offer context-appropriate and effective choices as CVA partners, including those where C2FI – if defined as engagement with formal financial institutions – is considered unlikely to succeed55. Indeed, research on digital financial inclusion in several Asian countries found that local savings groups can be seen as an easier and more immediate way to access funds when needed, for example in an emergency, as compared to a bank account. Similarly, where the local markets in which people meet their daily needs (groceries, health, etc.) are (physical) cash-based, this tends to ‘encourage reliance on a cash economy’60.

Other evidence highlights the importance of designing CVA from a user-centred perspective if it is to help achieve genuine financial inclusion. This requires a good understanding of how people use different financial services. It also requires that recipients have a choice over the transfer modality and the account into which money is paid61 , rather than limiting people to one provider or a system that does not offer the services they require (see Chapter 1 on People-centred CVA and Chapter 7 on Data and digitalization for more on this topic). If financial services do not meet what users need, recipients are more likely to cash out funds, which requires an agent network or withdrawal infrastructure with sufficient liquidity –62 which can be a constraint in some digital payment systems.

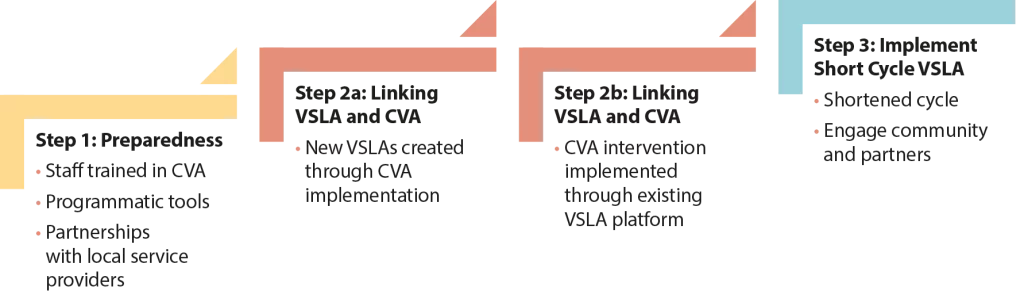

Box 8.5: CARE’s Village Savings and Loans Associations in Emergencies (VSLAIE)

The VSLA model focuses on low cost, self-administered informal financial services – with the ability to link to formal financial institutions where available. CARE’s research has found that combining VSLAs

and CVA can support improved outcomes and more efficient and effective interventions for crisis affected populations, supporting people who otherwise have little or no access to financial resources

and services. It can also increase the role of women in financial decision-making.

The VSLAiE model has been designed to support the recovery and resilience of people in emergencies through three stages. Preparedness is critical, including staff capacities and partnerships with relevant

local actors (e.g., CBOs, FSPs). Integrating CVA into VSLAs can be done by targeting CVA recipients to form new VSLAs and by using the existing VSLAs to improve the design and implementation of CVA.

The traditional 12-month VSLA cycle can be shortened to meet the needs of displaced populations who are often mobile and in transition. Adapted training, the use of digital platforms, and working through

local organizations to help connect potential group members are methods that can be used to address the needs of populations in fragile contexts. The timing of cash transfers to support capitalization of the groups is important to help maintain key principles of group autonomy and ownership.

CARE’S Vsla in Emergencies (VSLAiE) 3 Stage Model

Source: Adapted from CARE (2021) Combining VSLAs and Cash Transfers to Improve Humanitarian Outcomes

There is a reinforcing relationship between financial inclusion and the extent to which people’s livelihoods afford them a sustainable source of income; while people living in poverty require financial services as much as any other demographic, they are less likely to be able to access formal financial services and more likely to seek out, and use, informal financial services a sometimes even more than other segments of the population.

“We are looking more at financial inclusion in programme design, especially digital financial inclusion, with a women-centred focus as well. We’ve had discussions about this for a long time in the cash world, but it’s a difficult nut to crack. Especially if we think of the transfer values provided, which are often not enough to really talk about savings and getting a credit history, etc. Of course, this links to so many other areas, including financial infrastructure.”

(FGD – Asia Pacific)

The Forced Migration review found that ‘financial services did not lead to fulsome (by which the authors mean robust or profitable) livelihoods for refugees but that fulsome livelihoods led to increasing demand for a range of financial services’63 . A regulatory environment that allows recipients to hold money in their own names is also important as it allows people to build a financial history and incentivizes FSPs to expand the services they offer. In turn, this increases the resilience of crisis-affected populations and allows them to contribute to economic growth64 .

“Real added value lies beyond just scale. It’s this complementarity between our financial inclusion programming, our market systems programming, our food security programming.”

(Mercy Corps)

“Finding pathways to reach those who are entirely disconnected from digital and financial services – ‘unseen people’ – is an upcoming challenge. CVA can help with that. Financial inclusion and digitalization are two future challenges and opportunities more than ever.”

(World Vision International)

Issues with digital literacy, which frequently intersects with overall literacy and/or financial literacy, remains a concern for mobile money users in some contexts. For example, it was found that ‘31% of mobile money account holders in Sub-Saharan Africa cannot use their account without help’65. Mercy Corps found that providing financial health and literacy training alongside cash transfers resulted in greater impacts on, ‘food security, employment, intercommunity relationships, and perceptions of their economic and physical security’66 . For example, support in developing financial management skills helped reduce anxieties about meeting economic needs67 . Similarly, WFP found that delivering financial and digital literacy training alongside CVA was important for successful financial inclusion and that training had to be customized to the target population, including identifying specific financial products that might be useful for them68. It is recognized that ‘moving from CVA to financial inclusion will require a concerted effort by stakeholders, working together to overcome existing barriers, particularly regulatory hurdles, limited networks and digital payments infrastructure, and low levels of digital and financial literacy’55.

Graph 8.6: Fi Pathway based on digital mechanisms and engagement with formal financial institutions

The graphic demonstrates how cash transfers can lead to formal, digital financial inclusion and in turn resilience and economic growth70.

Despite some progress and strong interest, evidence remains limited and orientated towards one conceptualization of financial inclusion. As work on financial inclusion and CVA moves forward, local, national and international models of inclusion need to be considered and advanced according to user preferences and context. In support of such efforts, further evidence is still expressly needed.

Implications for the future: Areas for strategic debate and priority actions

Areas for strategic debate

Our analysis highlighted the following considerations to inform further thinking and progress in this area.

How can more effective relationships between sectoral programming and MPC be developed? Despite some progress over the years, the interrelationships between MPC and sectoral programming are still frequently contested, particularly concerning resource allocations and the achievement of respective outcomes. The lack of consistent or standardized approach to the design and coordination of MPC, including in relation to sectoral CVA, has contributed to these tensions. There is some optimism that the new cash coordination model, with its formalized place in the humanitarian system, will provide opportunities to better address this issue. The global Cash Advisory Group has been tasked with developing guidance on MPC for the 2024 HRP cycle. However, given the differing perspectives on how cash would be most effectively deployed in terms of MPC and/or sector-specific CVA, easy or generalizable solutions are not likely to be forthcoming.

Can a balance be struck between technical priorities and people’s preferences when designing complementary interventions, particularly in under-resourced responses? The rationale for complementary programming is compelling, with some arguing that this should be the default approach to intervention design. One note of caution is in ensuring people’s preferences are given necessary weight alongside the technical priorities of implementing agencies in the design of complementary programming. Determining which combinations of assistance are most effective, and the relative costs of implementing them, requires a willingness to experiment, based on sound analysis, to generate evidence. For example, where relevant this should show that additional costs for complementary activities do not compromise the adequacy of the cash transfer to the detriment of the overall impact. This may include recognizing where complementary activities are not required, and maximizing cash transfers, for example, is the best option. These issues may be more acutely felt in more resource constrained responses.

How can CVA be designed to better facilitate financial inclusion, including incorporating informal and community-based mechanisms? The potential use of CVA as a springboard to financial inclusion has consistently been shown to depend on a suitable operational context and target group, and a tailored programme design. In many crisis-affected contexts, there are supply and/or demand-side challenges to this. Financial inclusion is frequently defined, implicitly, or explicitly, in terms of engagement with formal financial institutions and services. Within CVA this makes sense to the extent that the entry point for financial inclusion is usually via payment solutions from formal FSPs. However, in many contexts, different formal structures – such as micro-finance institutions – as well as informal and community-based mechanisms play a critical role in people’s financial management and service access, although engaging with these mechanisms typically falls outside the scope of humanitarian response as the system is currently structured. With greater focus on locally-led response, there is need for more focus on the opportunities to strengthen responses by working with different mechanisms and giving more focus to ‘bottom up’ financial inclusion. Designing CVA to support financial inclusion, building on informal and formal mechanisms, should recognize the need to navigate different ways of working between large-scale CVA and working with VSLAs, for example. One function could be in finding opportunities for ‘bridging the gap between formal and informal access to finance’, which has been shown to ‘boost financial inclusion and financial health’71.

Priority actions

In relation to the strategic debates above and other key findings in this chapter, the following are recommended as priority actions for stakeholders.

- Humanitarian actors, including operational agencies, CWGs and clusters, should encourage and adopt systematic tracking of sectoral CVA and MPC. The lack of reliable and publicly accessible data limits the quantification, monitoring and coordination of both MPC and sectoral cash. While not a panacea for associated challenges, better data could help identify and address some barriers and enable more effective evaluation of the types of assistance provided, where, and the relative impacts.

- Operational agencies, CWGs and clusters should encourage and engage in multisectoral assessment and analysis processes, including the roll-out of the JIAF 2.0. Such joint processes have been consistently identified as critical to facilitating greater and more effective uptake of both MPC and sectoral CVA, including combined with complementary activities.

- Sectoral stakeholders and others working to support the effective use of CVA for sectoral outcomes should identify and explore opportunities for more cross-sectoral engagement to help overcome common barriers to the uptake of CVA. This can be done with an appreciation of the specificities of the use of CVA in different sectors.

- CWGs and clusters should aim to use MEB processes to their full potential to facilitate more collaboration and understanding between sectors and cash actors. This has the potential to be used as a springboard to ongoing collaboration in assessments and analysis, and the development of better cross-response synergies in programme design. At the same time, CWGs and clusters should avoid unduly technical, time-consuming and costly MEB processes that risk hindering rather than supporting people-centred CVA.

- Humanitarian actors should continue to make use of jointly developed metrics and tools for monitoring and evaluating the impacts of both MPC and sector-specific CVA. It is also important to engage in efforts to share and/or consolidate results to both better understand the outcomes of different interventions and identify where improvements are required to metrics and tools.

- CWGs, donors, and relevant intersectoral and sectoral representatives should work together to agree guidelines on the respective functions of and relationships between MPC and sector-specific CVA, building on what is already outlined in the new cash coordination model. So far as possible, this should happen in advance of or at the outset of a response. Ideally it would follow a similar approach across responses, but in practical terms will likely be tailored to a given response and/or country, including in terms of linkages to social assistance and cash-based anticipatory action.

- Humanitarian actors should systematically explore and document the effectiveness of different combinations of activities (i.e., complementary programming) with regards to various outcomes. The objective should be to maximize outcomes and synergies between programmes to achieve impacts that are greater than the sum of the constituent parts, including identifying and investing in effective referral mechanisms.

- Humanitarian actors should systematically incorporate feasibility analysis for financial inclusion (opportunities and challenges) into CVA design (and funding) processes, and gather and document evidence of the outcomes where relevant. This should include both formal and informal financial services and mechanisms. To initiate that process, humanitarian actors could start by engaging with key stakeholders including local communities, formal and informal financial organizations, and relevant regulators, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the financial landscape and opportunities. Another engagement could be to conduct an in-depth contextual analysis to assess the specific financial needs, preferences, and challenges of the target population in a given humanitarian setting.

1. CALP Glossary definition of Basic Needs/Essential Needs: The concept of basic or essential needs refers to the essential goods, utilities, services, and/or resources required on a regular or seasonal basis by households to ensure their long-term survival AND minimum living standards, without resorting to negative coping mechanisms or compromising their health, dignity, and essential livelihood assets. However, there is no global definition of the precise range and categories of need that constitute basic needs, which will depend on the context and what people themselves consider the most important aspects to ensure their survival and wellbeing. Assistance to address basic needs can be delivered through a range of modalities (including cash transfers, vouchers, in-kind and services), and might include both multi-purpose cash assistance (MPC) and sector-specific interventions.

2. CALP (2020) State of the World’s Cash 2020. CALP

3. Development Initiatives (2022) Tracking Cash and Voucher Assistance. Development Initiatives:

4. Development Initiatives (2022) Tracking Cash and Voucher Assistance. Development Initiatives.

5. https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/1124/summary for 2022 – In Ukraine, MPCA is the second largest funding requirement and fifth funding obtained category with US$958.6 million required (against US$3.95 billion for the total requirement of the plan) and US$431.7 million funded (against US$1.7 billion funded).

6. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP: https://www.calpnetwork.org/publication/increasing-the-use-of-humanitarian-cash-and-voucher-assistance/

7. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP

8. E.g., CALP (2020) State of World’s Cash – p.48: “The capacity to do quality intersectoral analysis and design, beyond the sector siloes, is the key issue to address …”:

9. E.g., CALP (2020) State of World’s Cash: “All humanitarian actors should support the strengthening and systematic use of response analysis underpinned by robust multisector needs assessments. These should incorporate both multi-purpose cash and sector-specific CVA within an integrated programming framework.”

11. Kreidler, C. and Taylor, G. (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP

12. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023) The Grand Bargain in 2022: An independent review. HPG commissioned report. London: OD

14. https://phap.org/PHAP/Events/OEV2023/230607.aspx

15. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP

16. Grand Bargain Cash Workstream. (2022) Multipurpose Cash Outcome Indicators and Guidance

17. Save the Children (2022) Multipurpose Cash Assistance (MPCA) Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL) Toolkit: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/multipurpose-cash-assistance-mpca-monitoring-evaluation-accountability-and-learning-meal-toolkit/

18. World Vision (2021) Cash & Voucher Programming Compendium of Indicators

19. The primary concerns about MPC amongst sector actors highlighted in State of the World’s Cash 2020 report were: (a) implications for accountability, if sector standards are not met; (b) whether and how responsibility is shared between actors leading MPC and wider sectoral programming aspiring towards specific sector outcomes; and (c) how MPC can be integrated into a comprehensive multisectoral response.

20. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP

21. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance.

22. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N.(2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP

23. Save the Children (2022) Multipurpose Cash Assistance (MPCA) Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL) Toolkit[footnote]Save the Children (2022) Multipurpose Cash Assistance (MPCA) Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL) Toolkit. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/multipurpose-cash-assistance-mpca-monitoring-evaluation-accountability-and-learning-meal-toolkit/

24. Key Aid (2023) Rapid Reflection on the Scale-up of Cash Coordination for the Syria Earthquake Response. CALP

25. Key Aid (2023) Rapid Reflection on the Scale-up of Cash Coordination for the Syria Earthquake Response – North West Syria. CALP

26. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP

27. Juillard, H. et al. (2020) Cash Assistance: How design influences value for money. Paris: Key Aid Consulting

28. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP

29. Lawson-McDowall, J., Truelove, S., and Young, P. (2022) Calculating the Minimum Expenditure Basket: A guide to best practice. CALP.

30. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N.(2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP

31. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N.(2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance.

32. Contextual appropriateness would likely include, but not necessarily be limited to, considerations of market functionality, household preferences and access, availability of adequate financial service providers and regulations.

33. Development Initiatives (2022) Tracking Cash and Voucher Assistance

34. Development Initiatives (2022) Tracking Cash and Voucher Assistance

35. Case studies in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso and Jordan available at: https://www.calpnetwork.org/collection/cva-and-health-case-studies-from-jordan-burkina-faso-and-bangladesh/

36. Boulinaud M. and Ossandon M. (2023) Evidence and Practice Review of the Use of Cash Transfers in Contexts of Acute Food Insecurity. Rome, Global Food Security Cluster:

37. Rapid Seed System Security Assessment (RSSSA) Tools | CRS: https://www.crs.org/our-work-overseas/research-publications/rapid-seed-system-security-assessment-rsssa-tools

38. Kreidler, C. and Reiger, N. (2022) Increasing the Use of Humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance. CALP.; Development Initiatives (2022) Tracking Cash and Voucher Assistance

39. Boulinaud M. and Ossandon M. (2023) Evidence and Practice Review of the Use of Cash Transfers in Contexts of Acute Food Insecurity. Rome, Global Food Security Cluster

40. Boulinaud M. and Ossandon M. (2023) Evidence and Practice Review of the Use of Cash Transfers in Contexts of Acute Food Insecurity. Rome, Global Food Security Cluster