The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Chapter 4: Cash Coordination

Summary

Key findings

- There has been progress on cash coordination.

- It is too early to know if the new cash coordination model will deliver on ambitions.

- Views on the extent of donor commitment towards cash coordination are mixed.

- The increased focus on locally-led cash coordination is welcomed but faces challenges.

- Some feel an opportunity for a transformational solution has been missed.

Strategic debates

- Will the new cash coordination model deliver effective change?

- Is more radical change needed to achieve the potential of CVA?

Priority actions

- The CAG should prioritize efforts to complete a strategic resourcing plan, with an overview of the resources needed for the coordination model at country level, including support to national actors, and the CAG itself.

- Donors should, once priorities are agreed upon, commit funding to support the new cash coordination model so it can achieve its objectives of predictable, accountable, people-centred and locally-led coordination of CVA.

- CWG, CAG, HCTs and other relevant stakeholders should ensure systematic sharing and learning about cash coordination between responses. This includes with non-IASC settings.

- CWGs and the CAG should harness opportunities to engage with wider humanitarian reform processes to further strengthen cash coordination, including the current ERC’s Flagship Initiative

- The CAG, CWGs, donors, local actors and other interested stakeholders should harness the opportunity of the planned review of the cash coordination model to strengthen coordination linkages with other reform processes, increase linkages with social protection, and strengthen the leadership of local actors.

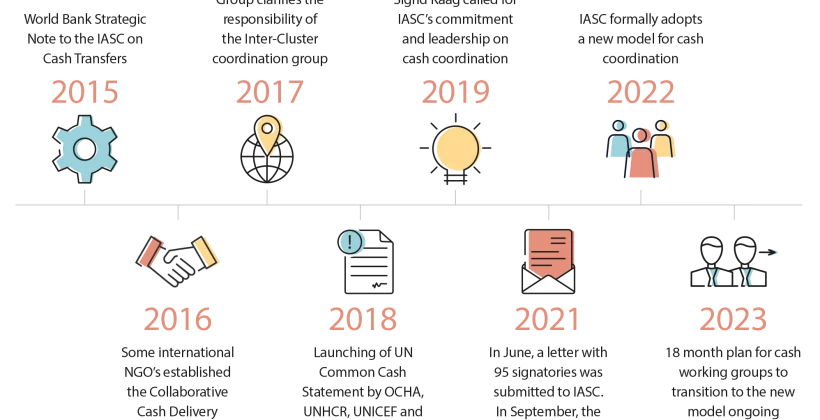

Progress on cash coordination

The longstanding challenges associated with cash coordination have been extensively explored in previous reports1. The State of the World’s Cash 2020 report recommended continued advocacy for standardizing a predictable approach to cash coordination and ensuring adequate funding for Cash Working Groups (CWGs). Without a common understanding of who was responsible for what, or reliable resourcing for cash coordination mechanisms, the opportunities to improve the effectiveness of cash assistance were being lost.

While the issue became increasingly urgent with the growing use of CVA, the challenges of cash coordination remained unresolved for over a decade despite several initiatives attempting to address them. However, in September 2021, USAID and CALP coordinated a breakthrough when a Call for Action2 resulted in 95 organizations signing a letter to the Emergency Response Coordinator calling for change. The establishment of the Grand Bargain 2.0 Cash Coordination Caucus followed in October 2021.

Figure 4.1: Cash Coordination Timeline

The Grand Bargain Eminent Person led the Caucus, which involved national and international agencies, donors, and technical networks3. The Caucus aimed to identify arrangements for accountable, predictable, effective, and efficient coordination of cash assistance making clear who will do what, with what resources and to what end, and to improve outcomes for, accountability to and engagement of crisis-affected people and communities 4

The IASC endorsed the new cash coordination model in March 2022. The outcome document emphasized the importance of a people-centred approach and locally-led response, including consideration of linkages with social protection systems where relevant and appropriate5. A review of the model is planned two years after implementation to identify progress, challenges, and any adaptations required 6.

Box 4.1: What is the Cash Coordination Model7

The new model applies to two contexts: (a) IASC settings, and (b) refugee settings. Questions remain as to what cash coordination models will be used in what the Cash Advisory Group (CAG) calls ‘non-IASC settings’.

At country level

- OCHA is accountable for cash coordination in IASC and mixed settings, while UNHCR is accountable in refugee settings.

- CWGs are accountable to the Inter Sector/Inter Cluster Coordination Group and responsible to support their members and constituents (e.g., operational cash actors in country).

- Existing CWGs will be formalized with new standardized Terms of Reference.

- In IASC settings, there will be a programmatic and a non-programmatic co-chair of the CWGs. OCHA is responsible for providing the non-programmatic co-chair. The programmatic co-chair should be an operational entity, identified via a transparent voting process. The model places particular emphasis on the importance of local actor leadership. In refugee settings (under UNHCR), there will be no nonprogrammatic co-chair and attention will be paid to government and local actor co-chairs.

At global level

- A new global Cash Advisory Group (CAG) has been established. It is responsible for developing standards, global tools, guidance, and decision-making protocols and supports requests for best practices or other needs from country CWGs.

Notably, there is no official reporting line or link between the CAG and country CWGs. CWGs are accountable to the Inter Sector/Inter Cluster Coordination Group in each country, or to the Resident Coordinator/Humanitarian Coordinator in settings with no IASC or refugee coordination structure in place. It is for the humanitarian leadership and CWG to jointly decide how to best transition to the new model and monitor progress. The CAG is expected to provide support and engage with CWGs in line with its agreed functions.

Alongside defining a standard leadership structure, some steps have been taken to improve issues of operational predictability. Standard Terms of Reference to guide the work of CWGs8 and the CAG9 have been finalized and Terms of Reference drafted for the co-chairs of the CWGs10.

Table 4.1: The purpose of CWGs and the CAG as defined in their agreed Terms of Reference

| Purpose of CWGs11 | Purpose of the CAG12 |

|

|

Too early to know if the cash coordination model will deliver

The process of transitioning to the new cash coordination model is at a relatively early stage, such that it’s not yet possible to evaluate any impact on coordination and programming. The “the IASC Deputy Directors endorsed the transition plan in September 2022. 27 IASC settings and 14 refugee settings were identified where the model should, initially, be rolled out, with transition to be completed by March 2024. As of the end of 2022, UNHCR reported that the model was being implemented in five of the 14 refugee settings in the plan, while OCHA reported it was in place in three of 27 non-refugee settings.

“DG ECHO strongly supports the orientations taken by the new IASC cash coordination model.” 13

“The huge potential and opportunity is that we now have a common model. We wanted predictability. We wanted cash and cash coordination to have a formal place in the humanitarian architecture.” Focus Group Discussion.

Many stakeholders positively view the agreement on the model and the opportunities it presents14

According to the Grand Bargain independent review of 2022, the majority of the 66 Grand Bargain signatories believe the cash coordination model ‘provides predictability and clarity on coordination of CVA at country level’. They also felt that ‘the model was a step forward and there are high expectations that it will enable more efficient and effective CVA responses’15. Most key informants to this study expressed satisfaction that IASC had reached an agreement and endorsed the model. While there was

acknowledgement that it does not constitute a ‘radical outcome’, it was also noted that ‘incremental steps to changing things are still moves forward’, with the potential to support larger scale change. The majority of CVA focal points for the Global Clusters expressed their support for the new model, although at least one cluster representative emphasized that their support was contingent on the fact that the model maintains responsibilities for sector-specific CVA with the respective clusters, rather than the CWG (see Chapter 8 for more on cluster engagement with CVA, including in relation to MPC).

This is not just about cash actors, but about opportunities for better quality analysis, as the role of CWGs is now formalized and they inform analysis and response planning as part of the broader ICCG and cluster discussions.” (UN agency).

Some key informants believe that the new model could provide significant opportunities to: (a) improve the quality of humanitarian responses overall as the role of CWGs is now formalized in response analysis (see Chapter 5 on Preparedness and capacity) and (b) to increase the use of cash further, particularly multi-purpose cash (MPC). The lack of clear ownership of MPC in previous, less formalized cash coordination models, is considered to have been a systemic blocker to increasing its use. With the new model providing clarity – as per the TOR – on the responsibilities of the CWG in integrating MPC into response plans and processes, the idea is that there will be more scope to scale MPC. While key informants noted that it remains to be seen how this will work in practice, they also highlighted that some stakeholders, including donors, expect the new model will facilitate an increase in CVA, particularly MPC. It was also highlighted that the additional capacity available with two (resourced) cash coordinator roles per CWG (envisaged in the plan) should better enable CWGs to own and engage in relevant processes, for example market assessment and monitoring.

There are unanswered questions regarding operationalization and resourcing of the new model. Although broadly positive that a formal cash coordination model has been agreed, stakeholders have raised questions and concerns about the transition process and operationalizing the model. Key informants to this report perceived a good understanding of the new model at global level16 but there is concern that it is not yet understood nor has buy-in at country level. This was also reflected in responses to a survey conducted by the CAG where concerns were raised, for example, about how functioning CWGs with structures that don’t match the new model should be managed without dismantling what is already working. Others noted the potential for the new model to be seen as a threat to existing CWGs and CWG leads, particularly where there is confusion about what the transition will entail. There were also questions about what a ‘non-programmatic’ lead of a CWG really means in practice.

Research for the Grand Bargain annual report also highlighted that some people have questions about commitments to and capacities for rolling out the model across key stakeholders17. For example, CVA focal points of the Global Clusters stressed the importance of training and capacity development on the new model for cluster coordinators in-country. One UN agency noted that while the high-level commitment is there, translating the new model for cash coordination into practice across a large organization takes time as staffing and capacities come on board. These reflections chime with several key informants’ wider concerns about the slow pace of the transition. However, it was also noted that ‘this was to be anticipated given the nature of the change, and that it would take time to build the capacities required to enable implementation across a range of contexts’18.

“A source of frustration is that the need for predictability that has got us to where we are is the very issue that is still unclear; that is, resourcing and capacity.” FGD participant.

Key informants commonly noted that, a year after it was endorsed and despite global commitments to move forward, it is still unclear what resources are needed to ensure the model delivers on promises and concrete funding commitments are lacking. There are concerns that if the model is not sufficiently resourced, it will not resolve the problems that exist nor harness the opportunities that it was established to address. These concerns cover both the funding of programmatic co-chairs (including local/national actors) and information management roles, and whether OCHA will prioritize resources to ensure its Country Office staff can assume the planned co-leadership role of CWGs, including providing technical support to local/national actors as co-leads.

Views on the role of donors and the extent of their commitment are mixed. There is a consensus on donors’ critical role in pushing for the caucus and securing agreement on the model, but there was a sense that since then, ‘donors have stepped back a little in their engagement to allow operational partners to move ahead with implementation of the coordination model’[footnote] Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023)[/footnote]. Donor engagement is considered essential in relation to resourcing and maintaining pressure and support, globally and nationally, to push through the transition plans. The Donor Cash Forum (DCF) has indicated it recognizes its role in mobilizing internal and external stakeholders, including supporting local actor engagement (see below), and the development of a resourcing plan. In April 2023, the CAG and DCF agreed to establish a task team on resourcing the cash coordination transition, which will prepare a comprehensive resourcing plan for stakeholder feedback. This is intended to provide a joint way forward, although there is an important caveat that task team engagement does not equate to a commitment from any CAG or DCF member to fund any specific proposal.

Reflecting on the issue of resourcing, one key informant expressed a note of caution that funding alone will be insufficient to shift the effectiveness of cash coordination. There is also the need for a system wide shift that goes beyond cash in many respects, bringing all relevant actors on board, from humanitarian coordinators (HCs) through to the clusters, particularly in navigating difficult political factors and decisions.

Box 4.2: Ukraine Cash Coordination

Opinions are mixed about the success of cash coordination in Ukraine.

Findings of the 2023 Grand Bargain Independent Review were largely positive: ‘Signatories generally felt that the cash response in Ukraine was well coordinated, was treated as a high-level priority with direct engagement of the Resident Coordinator/Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC), that systems and capacities at institutional level and across the system were in place to scale up quickly, and that functional links with the national social protection system were made appropriately given the protection and logistical challenges involved. But there were problems too, (including …) concerns about the exclusion of some local and national actors by a decision to require in-person participation in the CWG, and the unintentional exclusion of some vulnerable groups due to over-reliance on a digitalized system that presented access problems for the elderly and other groups. Several signatories and experts asserted that Ukraine should not be understood as a common standard or even a real ‘test’ of the model because too many factors were not replicable elsewhere – including the volume and speed of funding, widespread digitalization and high levels of local and national civil society and government capacities and systems’ (ibid: 82–83)[footnote] Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023)[/footnote].

The Operational Peer Review in Ukraine (forthcoming) provides a different, more challenging picture of the roll out of the new coordination model. According to the OPR, in 2022 approximately US$1.5 billion of CVA was delivered to vulnerable people. The OPR observed: ‘While the cash operation has been highly successful in scaling up and building an impressive architecture, there remain challenges with the new IASC cash coordination model and there is considerable dissatisfaction from UN and NGO participants and beneficiaries on issues such as targeting and multi-purpose cash vs. sectoral specific cash’ (ibid: 6).

A focus on locally-led cash coordination is welcomed but faces challenges

Localization is one of the principles that the new model is built on, with the objectives of enabling greater participation of national and local actors and helping to ensure decisions are made closer to and with greater accountability to crisis-affected populations21. All key informants welcome the central leadership role of local and national actors and highlighted it as one of the most important opportunities of the new model. For example, the DCF expressed the hope that ‘the local actor engagement prioritized in the cash coordination transition can serve as a precedent for the wider system’.

CAG members reflected that the model could provide concrete opportunities to explore systemic and contextual blockages to localizing CVA, while conceding local engagement at country and response level remains limited at this stage. The inclusion of representatives from several local organizations and networks in the CAG was highlighted as a positive step, with the caveat that it risks being tokenistic unless ambitions for local leadership at country level are achieved.

Multiple stakeholders expressed concerns about ensuring funding to enable meaningful engagement by local actors (see above on resourcing). Respondents for the Grand Bargain 2022 independent report shared similar sentiments. Equally, assuming funding is made available, questions were raised about what mechanisms would be used to ensure funding is accessible to all CWG co-leads, particularly local actors.

The CAG undertook key informant interviews in 2023 and these also identified important questions and concerns relating to the role of local actors (see Box 4.3). These included some issues relating to the capacities and relative experience of local actors. In addition to securing necessary funding, donors and international agencies frequently cited the importance of investing in capacity development and providing technical support. While highlighting local actors’ value added in coordination, some also expressed concerns about the risks of reinforcing negative stereotypes if local actors were pushed towards leading CWGs without the requisite experience or skill sets to do so effectively.

“Let’s be honest about where we’re not seeing as much progress – particularly in terms of local engagement. The model as it is being rolled out is helping to shift the narrative, but also opening other questions.” UN Agency.

“It is easy to say local actors don’t have the capacity to coordinate or to lead. In some contexts, this is probably true. However, for most local actors who cannot directly access institutional funding for programming, what they are left with is the question: ‘What’s in it for us to participate in these forums with international agencies while we can’t access funding?” FGD participant.

“A lot of our members are pushing for area-based coordination models –decentralized, context-led coordination based on the crisis geography. This is rather than the cluster system which is not resulting in effective complementarity or collaboration.” Key informant.

Box 4.3: Issues raised about the model through discussions with key informants (largely Local and National Actors) by the CAG in 2023

- CWGs, especially local and national members, value technical expertise. Many LNAs are never given the opportunity (or funding) to gain that experience.

- ‘Fly in’ short-term leadership roles (important for international decision-making) can alienate local and national actors.

- If local and national actors do not have a lot of CVA experience, how can they be expected to lead? What should their role be?

- The added value of local and national actors could be: sub national contextual expertise, community engagement/networks, and a focus on areas of interest (protection, social protection links, etc).

- Having experience with implementing cash at scale seems important to many. How can/should this be considered without undermining local and national actor roles?

- Key Performance Indicators need to be commonly defined, globally aggregated, yet contextualized.

At the same time, several key informants noted that a focus on the capacities of local actors puts the onus on local actors to engage in the coordination structures of internationally-led humanitarian response. This both ignores the lack of international actors’ engagement with local actors in the coordination spaces and seems based on an implied assumption of the value-added for local actors to engage in international coordination mechanisms (see Chapter 3 on Locally-led response). The fact that, in the medium-term at least, CWGs and other (international) coordination mechanisms are unlikely to operate in local languages, was also mentioned as a limiting factor.

One of the principles of cash coordination outlined in the caucus outcome document is to ‘consider linkages with social protection systems where relevant and appropriate’22. Members of the CAG noted that including linkages to social protection into the TORs for CWGs has helped to highlight the need to address this, although it’s still too early to tell what impact the new model might have. It was also noted that collaboration with the SPIAC-B Working Group on Linking Humanitarian Cash Assistance with Social Protection, which has coordination as a priority area of work, has been positive.

While recognizing that coordinating linkages to social protection faces multiple challenges in practice (see Chapter 6 on Linkages with social protection), it was felt that more could be done to ‘move the dial’ on this issue. This perspective was also reflected by some key informants to the latest Grand Bargain report, who felt that integrating CVA with social protection systems has not been given sufficient emphasis in cash coordination. Ukraine was identified as an example where some felt more could have been done23.

At the same time, several key informants and focus group participants commented that responsibility for building relationships with government ministries and linkages to social protection should not and cannot sit only with CWGs. For example, CAG members highlighted that communication with governments also needs to come from more senior levels such as the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) or Humanitarian Coordinator. The broader implications in terms of funding, operations and humanitarian principles that can follow from linking to social protection were also noted in relation to the limits of what a cash coordination mechanism could be expected to manage. Here, one key informant remarked that cash and cash coordination can highlight and be prominent in discussions related to coordinating the humanitarian-social protection development nexus, but that addressing issues will often need to happen elsewhere in the system.

A missed opportunity for a transformational solution?

Some informants voiced concerns that the new model is the wrong solution to the historical problem of effective cash coordination. They felt that working within the current humanitarian architecture and processes missed an opportunity to advance wider humanitarian reform and develop a cash coordination model that is ‘fit for the future’. For example, one key informant suggested that more holistic processes that don’t separate basic needs along sector-based lines are required if programming (and coordination) is to be effectively oriented to meeting peoples’ needs, with cash as a central modality.

“The cash coordination model – it wasn’t the right solution; it wasn’t a transformational solution. It was an incremental change solution that was almost a decade too late.” Key informant.

The recent launch of the Emergency Response Coordinator’s (ERC) ‘Flagship Initiative’ gives an indication of what the future of coordination could look like beyond the current humanitarian architecture. With pilots in 2023 in Colombia, South Sudan, Niger, and the Philippines, it aims to provide crisis-affected people with ‘a canvas to shape the response to help them, but without the use of traditional humanitarian coordination models or humanitarian programme cycle processes’24. Initial discussions in the Philippines, for example, focused on the potential to move to a primarily cash-based response, and an area-based, geographically-defined, approach to coordination that can enable greater community engagement and influence. Overall, despite the backing of the ERC, there are concerns about how far vested interests, particularly from the larger agencies, might block progress25. It remains to be seen how the Flagship Initiative will develop in practice, but opportunities exist to embed local leadership and ensure alignment with social protection and wider development work. This initiative and others require new thinking and ways of working. In theory at least, the new cash coordination model should be well placed to adapt to new ways of working if its ambitions are achieved.

Implications for the future: Areas for strategic debate and priority actions

Areas for strategic debate

Our analysis highlighted the following considerations to inform further thinking and progress in this area.

- Will the new cash coordination model deliver effective change? There are now significant opportunities for the cash coordination model to enable change with its formal place agreed in the humanitarian architecture and its ambitions for local leadership and linkages with social protection wherever appropriate. With structures agreed, questions remain about the pace of change and how it will be resourced. Further, the model currently applies just to IASC and refugee settings. Clarity is needed about other settings when strong government leadership is not already charting the way. The CAG has the potential to support this.

- Is more radical change needed to achieve the potential of CVA? Some believe that the new cash coordination model provides a valuable, evolutionary step forward. Others feel it represents an opportunity lost and that it papers over the need for more radical change. Linked to this, a priority action that remains outstanding from the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report is about the more fundamental changes to the coordination system overall (not cash-specific). Whether or not the new cash coordination model will help contribute to this type of change is debatable.

Priority actions

In relation to the strategic debates above and other key findings in this chapter, the following are recommended as priority actions for stakeholders.

- The CAG should prioritize efforts to complete a strategic resourcing plan, with an overview of the resources needed for the coordination model at country level, including support to national actors, and the CAG itself.

- Donors should, once priorities are agreed upon, commit funding to support the new cash coordination model so it can achieve its objectives of predictable, accountable, people-centred and locally-led coordination of CVA.

- CWG, CAG, HCTs and other relevant stakeholders should ensure systematic sharing and learning about coordination between responses. This includes with non-IASC settings.

- CWGs and the CAG should harness opportunities to engage with wider humanitarian reform processes to further strengthen cash coordination, such as the current ERC’s Flagship Initiative.

- The CAG, CWGs, donors, local actors and other interested stakeholders should harness the opportunity of the planned review of the cash coordination model to strengthen linkages with other reform process, linkages with social protection and leadership of local actors.

1. E.g., CALP State of the World’s Cash Reports – 2020 and 2018; and Grand Bargain Annual Reports

3. The Eminent Person led the caucus with support from the Norwegian Refugee Council, involved A4EP, the Collaborative Cash Delivery Network (CCD), EU/DG ECHO and the US Agency for International Development Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) (representing the Donor Cash Forum), OCHA, the IFRC, UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP and the World Bank (as observer) at both technical and principal levels. CashCap and CALP also participated as technical experts.

5. Grand Bargain (2022) Grand Bargain Cash Coordination Caucus Outcomes and Recommendations.

6. Global Cash Advisory Group (2023) IASC New Cash Coordination Model, Frequently Asked Questions.

7.

Global Cash Advisory Group (2023) IASC New Cash Coordination Model, Frequently Asked Questions.

https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/new-cash-coordination-model-frequently-asked-questions-faq

9. IASC (2022) Global Cash Advisory Group Terms of Reference 2022.

12. IASC (2022) Global Cash Advisory Group Terms of Reference 2022.

13. DG ECHO guidance note, March 2023.

15. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023) Grand Bargain Annual Independent Report.

16. Three focus group discussions (CAG, Global Cluster CVA focal points and the Donor Cash Forum) and 10 Key Informant Interviews (1 private sector, 4 UN officials, 2 donor and 3 INGO staff).

17. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023).

18. Ibid.

19. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023)

20. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023)

23. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023) Grand Bargain Annual Independent Report.

25. Alexander, J. (April 5 2023) What’s the ‘Flagship Initiative’, and how might it transform emergency aid? The New Humanitarian.