The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Chapter 6: Linkages with Social Protection

Summary

Key findings

- There has been progress on approaches for linking CVA and social protection, with COVID-19 accelerating interest and activity in this area.

- Donor interest is increasing; funding instruments now need to be adapted.

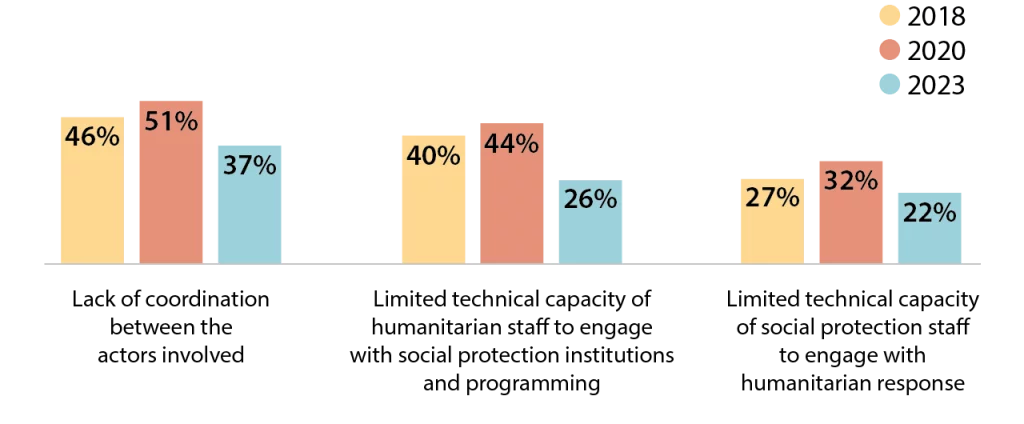

- Barriers to progress include limited technical capacity of staff; a lack of coordination between actors; and limitations in the interoperability of data and systems between governments and humanitarian organizations.

- Social protection systems should be adapted to enhance their role in crisis response.

- There are many ways that social protection and humanitarian CVA can be better linked, with pathways informed by context.

- There are opportunities and challenges with linkages in conflict settings.

Top 3 perceived barriers to linking CVA-SP: Comparative trends 2018 – 2023

Strategic debates

- How can conflicting humanitarian and development principles be balanced, so that CVA and social protection are linked effectively

- What considerations should guide principled action on linking CVA and social protection in conflict settings or where governments are not fulfilling their role as duty bearers?

- How can humanitarian and development actors better work together to support social protection system strengthening?

Priority actions

Recognizing that approaches to linking CVA and social protection should necessarily vary widely by context:

- Humanitarian and development actors should engage at country level in systematic, context-specific assessments to identify entry points for appropriate and meaningful CVA and social protection linkages.

- Humanitarian and development donors should come together during emergency preparedness planning to discuss financial strategies between humanitarian and development programmes.

- Humanitarian and development donors should set incentives for linking CVA and social protection recognizing that approaches need to vary widely by context.

- Humanitarian and social protection actors should increase linkages or integration between government-led crisis coordination structures, international humanitarian coordination architecture, and social protection. The UN Resident/HCOs or related authority in a country should enable this on the humanitarian side, to lead more strategic but also operational and technical groups.

- All actors should consider investing more in structured capacity strengthening of humanitarian stakeholders on social protection, and of development counterparts on humanitarian action to facilitate mutual understanding and joint ways of working.

There has been progress on approaches for linking CVA and social protection

At the time of publishing the State of the World’s Cash 2020 report, emerging experiences and literature on humanitarian CVA and social protection1 suggested that linking should not be thought of in the absolute terms outlined in the early typologies of shock-responsive social protection. Rather it suggested there could be a range of different ways and degrees to which humanitarian actors could link with social protection systems. Increased efforts to link, during the COVID-19 crisis and beyond, has confirmed this with government, development, and humanitarian actors innovating across a programming spectrum. The range of possible options for linking humanitarian action with social protection has become more nuanced and elaborate as a result. These are illustrated in Graph 6.1.

Graph 6.1: Options for leveraging social protection systems to meet needs during shocks

Source: SPACE infographic

“We are seeing new possibilities for linking CVA and social protection, moving from using social protection systems for response towards exploring possibility of linking humanitarian aid recipients into social protection data registries, or for humanitarian action to strengthen national systems.” (IFRC)

Several factors influence the opportunities for effective linkages, including the maturity of the social protection system, the geographical focus of the crisis, the capacity of the state, the nature and context of the crisis and the current role of humanitarians.

In some places, the scale up of social protection has been government-led, and humanitarian actors have assumed an auxiliary, financial, advocacy or technical support role. In others, humanitarian actors have leveraged elements of the social protection system (especially data) to support delivery. There has been greater realization of the importance of humanitarians coordinating directly-implemented CVA with government-led social protection. This includes its importance to align on aspects of programme design, to complement and fill gaps in adequacy or coverage of national responses, and the humanitarians’ role in supporting the continuity of social protection programmes during crises.

Meanwhile, in countries where social protection systems are less well developed, there is increasing interest in humanitarian CVA being an entry point for strengthening systems – through influencing or supporting an increase in coverage or adequacy of programmes, or efficiency and effectiveness of systems, or with a view to enabling a transition of populations from humanitarian to government-led support. The Grand Bargain Sub-Working Group research on Linking CVA and Social Protection in the COVID-19 response confirmed these trends.2 It also highlighted that humanitarian actors are still commonly maintaining a direct implementation role rather than supporting a fully integrated, nationally-led response. UNICEF is the exception, where since 2019 a government-first model has been applied to the extent possible, where appropriate, according to their corporate guidance.

Since 2020, a wide range of guidance and conceptual frameworks have emerged, to support efforts in this space3. What is striking is the consistency of approaches promoted across these publications. Common features include:

promoting the importance of a ‘systems’ rather than a programme-specific approach;

promoting the importance of a ‘systems’ rather than a programme-specific approach;

understanding entry points through systematic assessments of strengths and constraints in the system;

understanding entry points through systematic assessments of strengths and constraints in the system;

building blocks at policy, programme and administrative levels;

building blocks at policy, programme and administrative levels;

considering the benefits and possible risks and constraints inherent in different ways of working; and

considering the benefits and possible risks and constraints inherent in different ways of working; and

engaging across silos and sectors.

engaging across silos and sectors.

Multiple key informants in our research mentioned the guidance materials developed under the SPACE Facility4, reporting that their publications and the conceptual frameworks have been replicated in wider training and agency-specific products5. All this is helping build a more consistent understanding of options as well as methodological approaches to determine the way forward.

The importance of financial inclusion is discussed in Chapter 8 on CVA design.

COVID-19 accelerated interest and activity around CVA and social protection

The COVID-19 pandemic was a game changer for linking CVA and social protection. The unprecedented response to the pandemic saw a huge upturn in the scale of government cash assistance through social protection systems6. Almost 17% of the world’s population was covered with at least one COVID-19 related cash transfer payment between 2020 and 20217. In turn, the social protection response provided a clear rationale and entry point for linking humanitarian assistance (particularly cash) with national systems, with a simultaneous upsurge in interest and efforts among international development and humanitarian actors8. Key informants felt that: (a) the response contributed to a clearer realization that national social protection systems can provide an entry point to respond with CVA – quickly and to scale; and (b) the sheer scale of need led to enhanced collaboration between government and humanitarian partners9.

At a policy level, the position statements of donors and global networks10 were also reportedly influential for galvanizing action among implementers11. Several national governments actively requested international humanitarian actors to support national social protection12. Early indications suggest that the increased interest and activity has been sustained. For example, in 2022 the regional response to mass displacement caused by the war in Ukraine, the global responses to inflation, and the response to the Pakistan floods all have social protection linkages as a central theme13. Alongside this, regional cash working groups (CWGs) reported an upsurge in demand for discussions about linkages from their members. Data from CashCap mirrors this, reporting eight deployments focused on linking CVA and social protection in 2022 (compared to three between 2016 and 2020). Socialprotection.org also reports that adaptive social protection and humanitarian assistance were priority discussion topics in 2022 – second only to digital social protection14. This interest is also reflected in our survey, where ‘lack of support’ among social protection or humanitarian practitioners was the least frequently reported challenge to linking social protection and CVA (see Box 6.1 below). Looking ahead, it is anticipated that the impacts of climate change will further increase focus on these linkages as stated at the Global Forum on Adaptive Social Protection in 2023 (see also Chapter 9 on Climate and the environment).

Donor interest is increasing, now funding instruments need to be adapted

“Donors are talking the talk but not walking the walk on changing their internal administration. There are pockets where both sides [humanitarian and development] of donors come together, but this is based on personalities not policies. Funding instruments are not fit for purpose.” (UN agency)

Key informants shared the view that donors are increasingly interested in the topic of linkages. Several perceived that among development donors, there has been an increased effort to enhance flexibility in funding across the nexus. Key informants identified Germany and SDC as playing a leading role in this space; SIDA and Irish Aid also reportedly demonstrated flexibility on the use of development funding to support social protection responses and system strengthening15. There has also been investment in donor-funded technical facilities, with some success in promoting linkages between CVA and social protection through capacity strengthening and technical assistance16. In mid-2023, the Donor Cash Forum agreed that linkages would be one of its focus areas for collaboration. Another noted key change is the increasing role of the World Bank in supporting social protection and safety nets in crises contexts, with some increased acknowledgment of the role and partnerships with humanitarian (predominantly UN) actors17. In this case, some country-specific examples of improved collaboration and action across the nexus were noted, for example in Yemen.

Despite this interest, overall, key informants considered donors’ actions to advance this agenda limited. They perceived that there was generally little promotion of linking in humanitarian funding proposals; insufficient efforts to enhance internal coordination18 or connect humanitarian and development funding instruments and financing flows19; and insufficient investment in necessary preparedness measures and underlying system strengthening work. For example, key informants highlighted that while ECHO’s new cash policy, which promotes linkages, was well received, this isn’t yet filtering through to systematically influence country-level approaches and that funding instruments remain short-term and poorly connected with development instruments. Other recent studies have reached similar conclusions20. Key informants also noted that this topic was missing from the agenda of the European Humanitarian Forum in March 2023. Survey responses also reflected these views, respondents commonly perceived lack of funding to enable development of linkages as a barrier (see Box 6.1).

Barriers to progress on linking CVA and social protection

Survey respondents (Graph 6.2), key informants and those involved in focus group discussions identified several factors that they perceived to constrain the ability to link CVA with social protection. These are also consistently identified in other recent studies21. Interestingly, a comparison of data from previous State of the World’s Cash reports (Graph 6.3) shows the main barriers are the same now as those highlighted over the last five years, although it’s also notable that the weight given to the issues has reduced.

Graph 6.2: What are the biggest challenges to linking social protection and CVA? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Graph 6.3: Top 3 perceived barriers to linking CVA-SP: Comparative trends 2018 – 2023

“The way that organizations acted on linking CVA and social protection during the COVID-19 response varied depending on each organization’s current internal thinking and progress on the ‘linking humanitarian action and social protection’ trajectory … organizations more advanced in their thinking and activity … leverage tangible action in this space”. Smith (2021)22

An important enabler of creating linkages is investment in preparedness and capacity strengthening. These can be unpacked in terms of internal institutional preparedness and capacity of humanitarian organizations, as well as preparedness planning at the level of a country response.

Organizations are still at a relatively early stage in the journey to institutionalize these approaches. To make progress requires policy commitments, financial investments and building capacities across both social protection and humanitarian disciplines and across different types of institutions. These barriers are explored further in Chapter 5 on Preparedness and capacity.

Box 6.1: Barriers to linking with social protection in practice – the case of Ukraine

Ukraine’s well developed social protection system leverages the country’s robust financial system and range of digital technologies, and offers a solid platform for delivering large-scale cash transfers. Following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, there was strong government willingness to support the affected population and significant funding was available. The response perhaps should have been a model of partial to full integration, at least in government-controlled areas, yet seven months into the response, international humanitarian actors still faced difficulties in linking with the existing system.

- Preparedness and capacity of humanitarian actors. Problems included limited practical experience with this approach, or the steps to make decisions, among humanitarian actors deployed in Ukraine; lack of existing knowledge on the social protection system’s strengths and weaknesses; lack of sufficient knowledge or practical experience among donors to incentivize operational partners. This, plus the pressure to deliver quickly, led partners to implement parallel systems.

- Barriers to data sharing. Government social protection data systems held extensive data on affected Ukrainian populations, but data protection issues hampered the sharing of data with humanitarian actors. Concerns about upholding data protection laws are also a barrier to efforts to transition humanitarian caseloads to government.

- Difficulties in coordination. A CWG was established in Ukraine, with a task team on social protection that compiled and shared resources. Linkages between humanitarian and social protection actors (government, implementing partners and donors) were, for the most part, lacking. Government social protection actors, and donors of the social protection response, were not closely engaged with the CWG or task team which constrained planning for wider transition/integration of humanitarian-led CVA to the social protection system. This led to donors and the UN humanitarian and resident coordinator establishing a high-level coordination forum to convene senior decision-makers from across these humanitarian and development stakeholder groups. The forum focused on developing a medium- to long-term strategy and a roadmap to transition humanitarian cash assistance for conflict-affected people and IDPs to government.

Source: Compiled from various published reports23.

“Since COVID-19, lots of new actors including development actors have entered the space. The space has become very crowded, with agencies thinking about their added value and positioning themselves accordingly. But we are still not seeing organizations come together well to work collaboratively on this issue.” (UNICEF)

Survey respondents perceived coordination issues as the second biggest barrier. The importance of actors coordinating across preparing, designing, and implementing humanitarian responses linked with social protection systems is well accepted in principle, but practical experiences have shown that bringing together a multiplicity of actors, from different disciplines – and with different mandates, guiding principles, visions, and interests – is challenging in practice. Given the challenges to coordination of routine social protection, and international humanitarian action, and their inherently different coordination structures and architectures – which at times operate in parallel during an emergency response – it is not surprising that coordination is difficult.

Difficulties in coordination of CVA linked with social protection had been extensively highlighted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic24. While it continued to be problematic in the COVID-19 responses and beyond, experiences are providing more clarity on the influencing factors. FCDO and GIZ led policy research on factors enabling good coordination24 and found that the absence of these factors, summarized in 6.1, creates significant barriers to progress. Meanwhile, competition between humanitarian and development actors to highlight their comparative advantage, access funding and protect their operational space, is a major constraint to collaboration. Similar barriers were highlighted in our primary data collection.

All this highlights the importance of preparedness, given that many of the factors that enable good coordination require time and engagement to do well. They require action ahead of a shock, and this can be at odds with the short-term nature of funding and resourcing in humanitarian assistance.

The coordination of CVA and social protection is discussed further in Chapter 4 on Cash coordination.

Table 6.1 Factors influencing effective coordination of CVA and social protection

| Enablers of success | Promising practices |

|

|

Source: Adapted from Smith (2021)26, incorporating additional learning from recent literature and findings from key informant interviews.

In some countries in the Sahel, despite [humanitarian actors] stating that

their support to the COVID-19 response would also include a handover of data to strengthen national registries, this was then stopped, with senior decision makers citing concerns of data protection and risks. This has caused some frustration among government counterparts.” (Key informant)

Constraints to sharing data was the third most frequent barrier. On the one hand, as seen in Ukraine (Box 6.1), national regulations on data privacy can present a barrier to the sharing of social protection data with actors outside government. On the other hand, humanitarian actors remain reluctant to share data with governments (especially, but not only, in contexts of fragility and conflict), and have concerns about relying on government-derived data for targeting due to worries about the degree of impartiality or accuracy27.

While noting that agencies should uphold the interests of affected populations when making decisions about the use of data, some respondents were critical of the stance of some humanitarian actors in this area. They suggested that humanitarian principles were getting in the way of progress towards nationally owned approaches and national system building, perpetuating a continuing reliance on unsustainable humanitarian aid. They also highlighted the importance of engaging in negotiations on data access and protection prior to a crisis, again stressing the importance of preparedness.

Survey respondents (see Graph 6.2 above) also cited weak social protection systems in some contexts, limiting opportunities for linking. Various guidance and organizational strategies highlight that in such contexts humanitarian actors can approach linkages from the perspective of contributing to social protection system building, to provide an exit from humanitarian assistance. However, several key informants voiced concerns that the way these linkages are conceived or implemented is limiting effectiveness. Similar findings are borne out in other recent studies28, suggesting that actors need to carefully consider and refine these approaches to achieve meaningful change. Challenges noted include:

- Self-interest, and legacy systems. Key informants highlighted the increasing rhetoric among international humanitarian actors regarding their contributions to national system building, but felt that in practice engagement is weak, in terms of fully transitioning systems and strengthening government capacities. Others mentioned that ingrained processes or vested interests/competition meant that system designs were building from pre-existing ways of working in the humanitarian sector. These are not necessarily the optimum design for social protection and result in increased system complexity or creating systems that may not be best fit for purpose.

- Unrealistic planning and implementation timeframes and funding. Key informants highlighted a need to appreciate governments’ capacity constraints and that time frames for system building needed to be much longer – decades rather than years. The short timeframe of humanitarian funding is another noted constraint, underscoring the importance of development or transitional funding to support system building in such settings.

- Lack of political economy analysis. Over 22% of survey respondents (see Graph 6.2) cited lack of government support as a barrier to linking. While key informants reflected that governments may be open to collaboration with humanitarian actors and value their support to fill gaps, this may not follow through to an ambition to assume responsibility for, and finance, all aspects of social protection systems. Humanitarian actors’ insufficient engagement with governments to design something that is truly owned and in line with national priorities can undermine future transition. Key informants considered there was a need for more political economy analysis to understand governments’ challenges, interests and motivations.

- Challenges of measuring success. Monitoring of capacity and system building initiatives has tended to focus on outputs, with limited measurement of outcomes in terms of handover of systems, changes to policy commitments, or sustained resourcing29.

Adapting social protection systems to enhance their role in crisis response

A wealth of studies have documented learning from the social protection response to COVID-19 and country-specific literature has captured lessons from efforts to link CVA and social protection in other crises. This burgeoning knowledge base highlights gaps that need to be addressed to enhance the role that social protection systems play in crises. Discussants in this study commented on similar learning. These gaps have implications for humanitarian actors, whose skills and expertise (for example, in CVA data and delivery systems, in disaster risk reduction (DRR) and conflict sensitivity, and in terms of links to vulnerable populations) could add considerable value. It also implies a need for a longer term presence and engagement.

Gap 1: The need to build social protection system resilience

Pre-COVID-19, interest in linkages between CVA and social protection predominantly focused on actions that would allow social protection systems to be used to scale up and reach new needs, with less attention given to how crises affect social protection systems themselves. COVID-19 disrupted ‘routine’ social protection systems given restrictions on movement and risks of transmission, and staff sickness or quarantine. Governments and partners introduced various measures to accommodate disruptions and ensure continuity of cash assistance30. All this highlighted the absence of good practice measures for sustaining routine social protection in the face of shocks that cause disruption or damage to the systems31. Humanitarian actors in the MENA region (relating to conflict) and South-East Asia (relating to flooding)32 have also highlighted the need for measures to enhance the resilience of social protection systems and ensure service continuity in the face of disruption.

Gap 2: The need for investment in system building, with a shock lens, in crisis settings

COVID-19 experiences showed that leveraging social protection for shock response is more successful when the social protection system is mature. The maturity of social protection systems impacted shock responsiveness in terms of coverage, adequacy, duration, and timeliness. Low and lower-middle income countries with historically lower levels of social protection system maturity were generally worse affected. According to Oxfam, ‘eight out of ten countries did not manage to reach even half of their population’33. In part, this was caused by the fact that the pandemic shifted patterns of vulnerability, with some of those in need of income support not being part of the typical social protection or humanitarian caseload34. However, it was also caused because of gaps in financing, the coverage of routine social assistance, data, and delivery systems for the most vulnerable. Research and learning35 identified four factors that are important for enabling effective crisis response:

- Good coverage of affected populations.

- High-capacity workforce.

- Comprehensive, current, and inclusive information systems, backed up with ID systems.

- Digital delivery systems, with good penetration of financial service provision and underlying networks.

In this context, humanitarian actors made an important contribution to bridging gaps. For example, NGOs and national Red Cross Red Crescent Movement (RCRCM) Societies filled gaps in ‘last mile’ provision, especially in hard-to-reach areas through technical support and community engagement; UN agencies supported governments on cash delivery, targeting and data systems; and a range of partnerships supported innovations in rapid registration36. All these issues generated renewed focus on strengthening routine social protection systems ahead of crises37.

Even where systems are strong there can be challenges. In Kenya, where social protection systems are considered among the most advanced for shock responsive social protection, they did not respond in an effective and timely way to early signs of drought. Much more work remains to be done to fully understand the reasons behind the failure to scale up, but it appears to have been primarily a question of finance for the scale-up and, relatedly, limited government prioritization38. Key informants considered that such failings highlight that system building cannot be thought of as a discrete timebound event and underscore the importance of continuous engagement in system building for shock responsive social protection, and for health checks to identify changes in capacities, or new bottlenecks. They also highlighted the need for more consideration about how to protect gains made in system building from the risk of being lost through (for example) changes in government, or donor, interests.

Gap 3: The need for new ways of working to overcome barriers to social protection for particular groups

The exclusion of certain population groups from social protection systems is another noted gap in COVID-19 and other responses. Groups historically underserved include large sections of the working age population, who are poor or near poor and engaged in the informal economy – but who are excluded from social assistance and contributory schemes39. Another is refugees, displaced persons and migrant workers who are consistently among the most socioeconomically vulnerable but still generally ineligible for national social assistance programmes40. There is a clear case to be made for enhancing their inclusion, but experiences show that political (and related regulatory) and fiscal barriers to the inclusion of these groups cannot be underestimated41. To address these challenges, recent studies and pilot initiatives – especially in the Middle East and Africa, as well as in the Latin America and Caribbean region – are scoping out possible new ways of working, within which CVA has potential to act as a bridging tool. This includes for example, FAO’s work in Lebanon to link farmer registries with social protection registries, for future identification of rural workers through social protection data systems42; and early discussions in Jordan about ways to enhance host communities and refugees’ access to and uptake of social insurance, as part of a transition towards durable solutions43. Meanwhile, research by ODI and others is affirming the need to overcome barriers to transitioning from humanitarian to social protection approaches for displaced populations, through humanitarian and development partners’ coherent approaches to system building, which bring tangible benefits to displaced and host communities44. A toolkit has been launched in 2023 to support practitioners in this area45.

COVID-19 also highlighted gaps in social protection systems from a gender inclusion perspective, where women and girls were among the most vulnerable to the impacts of the crisis but where social protection systems were not well placed to reach and respond to gendered issues. Specialists working in this field46 highlighted that there is now greater awareness and discussion on the need to consider gender inclusion aspects in responses linked with social protection (confirmed in the BASIC (Better Assistance in Crises) mid-term review47 where GESI tools and guidance developed as part of SPACE have been widely commended). However, this was not yet perceived to be leading to visible changes to programme design.

Linkages in conflict settings: Challenges and opportunities

One notable gap in linking CVA and social protection has been in active conflict settings, and complex political situations where the government is not fulfilling its role as duty bearer for all population groups or where governance legitimacy is contested. In such contexts, there are concerns that linking social protection and CVA risks harming populations and not upholding humanitarian principles, and could undermine humanitarians’ neutrality. In these situations, even where social protection systems exist, humanitarian agencies almost always operate in parallel to government systems48. Our survey (see Graph 6.2) also highlights perceptions of government partiality as the fifth most cited barrier to linking.

With increasing trends in conflict worldwide, and the emergence of conflict in countries where national social protection systems have historically been strong, more attention and interest has been given to the question of social protection in conflict settings. For example, faced with the escalation of the conflict in Tigray and wider regions of Ethiopia which impacted on the continuity of social protection provision through the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP), FCDO Ethiopia commissioned research to collate global learning49 and build understanding of what options exist to support continuation of social protection in conflict settings. The research highlighted a range of practical innovations to adapt and preserve social protection programmes and ensure continued provision of cash transfers to vulnerable populations. These ranged from small design tweaks to more fundamental changes to institutional arrangements, government involvement and financial flows, depending on the context. The study highlights that non-government partners (including NGOs and UN) can support in various ways including through assuming direct implementation roles within the social protection delivery system, providing technical assistance, sharing experiences, and ensuring coordination of parallel humanitarian CVA to fill gaps (see Table 6.2).

Table 2.2 Promising practices for continuing social protection in conflict settings

Source: Adapted from the STAAR presentation50

| Conflict context | Promising practices for continuing social protection | Potential roles for humanitarian actors | |

| In locations with IDP influx due to conflict dynamics elsewhere in the country

|

Enabling portability of social protection payments for IDPs | Regulations/standard operating procedures that allow payments to be made outside place of origin | Advocacy for change, including sharing data on displacement |

| Mobile payments to communities in new locations | Support to system building – advocacy, technical assistance, operational support, sharing learning from CVA programmes | ||

| Use of e-payment mechanisms | |||

| Digital registry of beneficiaries, with common identifier, enabling use nationwide | |||

| Provide comparable support to host communities to avoid tensions | Coordination and alignment – humanitarian actors complement social protection, providing CVA to host communities | ||

| Community validation for re-registration/ID verification | Implementation support to labour intensive activities | ||

| Humanitarian assistance | Bridging support from humanitarian community to cover the period while social protection programmes enhance their portability | Coordination and alignment – humanitarian actors provide timebound CVA to fill gaps in social protection provision | |

| Conflict areas where delivery through social protection is broadly still feasible/where social protection systems are recovering following damage or disruption

|

Design tweaks and other measures to enhance system resilience, ensure safe access, simplify services, and ensure assistance remains relevant to conflict | Waive conditionalities |

Technical assistance/sharing learning from CVA programmes |

| Group payments together and frontload | |||

| Waive exit rules | |||

| Surge in staff capacity from other locations | |||

| Local authorities provide security | |||

| Use of e-payments | |||

| Conflict sensitive targeting | |||

| Remote registration/comms/monitoring (digital methods) | |||

| Introduce flexible payment processes | |||

| Standard operating procedures on how to operate in non-government-controlled areas | |||

| Route payments outside of national government, while still using social protection institutions for implementation | |||

| Partner with humanitarian actors to fill gaps in or support recovery of government capacities | Humanitarian partners assume implementation role on nationally-led social protection |

Direct involvement in supporting implementation (staff; resources; systems) |

|

| Support to rebuilding damaged social protection institutions (recruitment, salaries, operational budget, equipment, infrastructure …) | |||

| Independent monitoring | |||

| Where delivery by (central) government is not feasible due to conflict | Third party implementing agency | Switching implementation to go through humanitarian agency, preserving elements of social protection programme design, and social protection institutional engagement (local level engagement), to the extent possible |

Lead implementation role |

The research conclusions, some outlined below, can inform future work on linking CVA with social protection in conflict settings.

- Donors cannot continue to fund governments unconditionally and uncritically in a conflict setting, but this needs to be weighed-up against the risks of transitioning from nationally built to full parallel systems, loss of national capacity and undermining years, even decades, of development.

- ‘Government’ is not a homogeneous entity. The risks and sensitivities of engagement with government in conflict settings will vary according to the nature of the conflict, the location within a country, and the level/focus of engagement within government (central v local, for example). While political engagement and with bureaucrats may be problematic, several examples emerged of how humanitarian actors have found ways to engage with, and thus retain the capacities of, local government or technocratic staff. During interviews for this report, some key informants highlighted that this is not so different to having to engage with local authorities to ensure access for parallel humanitarian assistance.

- More evidence-based analysis and assessment of risks, by both social protection and humanitarian actors, is needed to reconcile differences in terms of principles and approaches. There were perceptions that the decisions of some humanitarians to work through parallel systems were not based on a robust examination of the risks to humanitarian principles. Equally, some humanitarian actors felt that those seeking to justify a continuation of support for social protection or linking of humanitarian action with social protection did insufficient risk analysis.

- Development and humanitarian actors need to make informed decisions about if or how existing support can be sustained, or new needs met during conflict through social protection, based on evidence, including through conflict analysis to effectively understand and manage risk.

- Learning from many contexts highlighted the importance of engaging community-level structures and decentralized social protection authorities, to ensure safe access and to understand and mitigate certain conflict risks.

Some similar points were raised in our focused group discussion with the SPIAC-B working group, where members demonstrated polarized views on this topic.

A recent ICRC blog51 concluded that while there are valid concerns about linkages in conflict settings, humanitarian actors should not automatically reject any type of engagement with social protection systems and outlined key considerations for how to move forward with linkages while ensuring a principled humanitarian approach. There are several initiatives underway that are seeking to further thinking in this area to identify appropriate and effective ways of working52.

Implications for the future: Areas for strategic debate and priority actions

Areas for strategic debate

Our analysis highlighted the following considerations to inform further thinking and progress in this area.

- How can sometimes conflicting humanitarian and development principles be balanced, so that CVA and social protection can be linked effectively? There is need for more work to reconcile the differences in priorities and positions between humanitarian actors (and concerns over undermining the humanitarian principles) and development actors (concerns with principles of national sovereignty, and the state’s responsibility for service delivery) to guide decisions on linking. There is a diversity of emergency and governance contexts where CVA and social protection can be linked. It might be helpful to nuance the application of humanitarian principles accordingly, since engagement with governments, or national systems, will not carry the same risks or considerations in all contexts, thus moving towards more nationally-led models where this makes sense.

- What key considerations should guide principled action on linking CVA and social protection in conflict settings or where governments are not fulfilling their role as duty bearers? Even in conflict settings it can be possible to engage with governments, and national systems, to varying degrees. It is important to develop a clearer vision to guide engagement in fragile-conflict affected situations with tools and approaches for humanitarian and development actors to undertake conflict-sensitive risk analysis. This implies the need for some form of escalation triggers/’red flag’ indicators, and phased approaches to identify when a context should transition from more government-led to more humanitarian-led models and vice versa. Links with protection actors could also support here.

- How can humanitarian and development counterparts better work together to support social protection system strengthening in fragile settings? Crises can present an ‘opportunity’ to enhance national systems due to increased attention, financing, and realization of the need for changes to adapt to new realities and vulnerabilities. It is recognized that nations vulnerable to crisis and without well-developed social protection systems must expand and improve these systems and remove barriers preventing people from accessing services. Humanitarian CVA actors can play a role in this transition – particularly in contexts where they are, de facto, filling a social protection role. But experience suggests that doing this well requires greater consideration of how to join up humanitarian and development funding (with the latter assuming the main role in system building), more thought to political economy factors around government ownership, and finding ways to better match systems and expertise with national priorities.

Priority actions

Based on these strategic debates and key findings in this chapter, including the recognition that approaches to linking CVA and social protection should necessarily vary widely by context, the following are recommended as priority actions for consideration.

- Humanitarian and development actors should engage in systematic, context-specific assessments to identify entry points for the most meaningful humanitarian and social protection linkages. They should do so in a coordinated way according to their comparative advantages. All humanitarian actors can play different roles to effectively support needs and fill gaps.

- Humanitarian and development donors should come together during emergencies to discuss financial strategy, linkages and continuity or integration of humanitarian assistance to development programmes. They should increase efforts to join humanitarian and development funding streams. Humanitarian and development funding decisions and objectives should be well sequenced and mutually reinforcing, contributing to a common strategy that outlines the scope and duration, and complementarities of both humanitarian and development funding.

- Humanitarian and development donors should set appropriate incentives, with clear and measurable commitments, for linking CVA and social protection. Donors could then assess funding proposals based on whether social protection approaches have been considered, and as relevant, the extent to which partners are approaching this in a coherent and coordinated way based on comparative advantages.

- Humanitarian and social protection actors should increase linkages or integration between humanitarian coordination architecture, social protection, and government-led crisis coordination structures. The UN Resident/HCOs or related authority in-country should enable this on the humanitarian side to lead strategic but also operational and technical groups.

- All actors should consider investing more in structured capacity strengthening of humanitarian stakeholders on social protection and of development counterparts on humanitarian action to facilitate mutual understanding and joint ways of working.

1. Such as Seyfert, K., Barca, V., Gentilini, U., Luthria, M.M. and Abbady, S. (2019) Unbundled: A Framework for Connecting Safety Nets and Humanitarian Assistance in Refugee Settings. Working Paper. The World Bank.

2. G. Smith (2021a) Grand Bargain Sub-Group on Linking Humanitarian Cash and Social Protection: Reflections on Member’s Activities in the Response to COVID-19. A report commissioned through Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC). Overall, actions mostly centred on directly implementing cash assistance programmes that built on elements of the social protection system (mentioned by 64% (14/22) of poll respondents) rather than channelling resources to government for nationally-led programmes (only 27% (6/22) of polled respondents mentioned this). Encouragingly, 77% (17/22) of poll respondents also reported having a role in providing technical support or capacity building for government systems. The diversity of approaches was also documented in a series of case studies published by the Grand Bargain Subgroup on Linking CVA and SP in 2021.

4. Since 2018 the UK government has funded the BASIC programme, which aims to support new and/or improved use of social protection approaches during crises. In 2020–21 this incorporated the Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert advice helpline (SPACE) which transitioned to the Social Protection Technical Assistance, Advice and Resources (STAAR) facility in 2022.

5. Key informants in our study reported that tools were helpful for guiding awareness raising on conceptual framing and guiding more systematic assessment and analysis to think through options for linking. This is confirmed in an evaluation, where respondents highlighted the high quality and practical orientation of the products and speed with which these were published compared to other sources. Tools and infographics developed under SPACE have been incorporated into CashCap’s approach to linking CVA and SP (see CashCap 2022), as well as CALP’s revised training and e-learning courses on linking CVA and SP, and country-level shock responsive social protection assessments in Cambodia and the State of Palestine. The Mid Term Review of BASIC found that SPACE guidance products reportedly influenced several multilateral organizations such as ECHO’s new cash policy. See: Maunder, N., McDonnell-Lenoach, V., Plank, G., Moore, N. and Begault, L. (2022). Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC) Performance Evaluation. Midline Report. A report by Integrity Research and Consultancy.

6. Bastagli, F. and Lowe, C. (2021) Social Protection Response to Covid-19 and Beyond: Emerging evidence and learning for future crisis, Working paper 614, ODI; U. Gentilini et al. (2021). Social Protection and Jobs Responses to Covid-19: A Real time review of country measures. ‘Living Paper’, Version 15, 14 May 2021. The World Bank. By the end of December 2020, 215 countries and territories had planned, introduced, or adapted social protection measures in response to COVID-19. As of January 2022, a total of 3,856 social protection measures were planned or implemented by 223 economies.

7. Bastagli, F. and Lowe, C. (2021) Social Protection Response to Covid-19 and Beyond: Emerging evidence and learning for future crises. Working Paper 614. ODI

8. Schoemaker, E. (2020) Linking Humanitarian and Social Protection Information Systems in the COVID-19 Response and Beyond. Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19: Expert Advice (SPACE); and Smith, G. (2021a). At the end of 2020, the Grand Bargain Sub-Working Group on Linking CVA and SP commissioned a research and reflections exercise with its members to understand the extent and the different ways in which member organizations had linked CVA and social protection in the COVID-19 response. Members of the Grand Bargain Sub-Working Group on Linking CVA and SP reported a massive shift, in terms of humanitarian organizations now identifying social protection as a key area of work and 19/22 polled members reported that their organizations had acted on linking during the response.

9. Bastagli, F. and Lowe, C. (2021) Social Protection Response to Covid-19 and Beyond: Emerging evidence and learning for future crises. Working Paper 614. ODI. Based on data from 98 programmes, government social protection responses took an average of 26 days between programme announcement and payment. Vertical extension of benefits took 18 days while expanding coverage took 30 days.

10. Including the Donor Cash Forum, Grand Bargain Sub-Working Group on Linking CVA and Social Protection, and SPIAC-B.

11. Smith, G. (2021) ‘Overcoming barriers to coordinating across social protection and humanitarian assistance – building on promising practices’, Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE), DAI Global UK Ltd, United Kingdom”

12. Smith, G. (2021) ‘Overcoming barriers to coordinating across social protection and humanitarian assistance – building on promising practices’, Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE), DAI Global UK Ltd, United Kingdom.’

13. Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., Iyengar, H.T.M.M., Valleriani, G., Okamura, Y., Urteaga, E.R. and Aziz, S. (2022) Tracking Global Social Protection Responses to Inflation: Living Paper v.4. Discussion Paper 2215, December 2022. World Bank Group. In 2022 there were 1,016 responses across 170 economies. Social assistance accounted for 29% of responses, 78% provided in the form of cash transfers. Out of the social assistance spending, almost 94% was spent on cash transfers (US$211.3 billion). Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., Iyengar, H.T.M.M., Valleriani, G., Okamura, Y., Urteaga, E.R. and Aziz, S. (2022). Tracking Social Protection Responses to Displacement in Ukraine and Other Countries. Discussion Paper 2209, June 2022. World Bank Group

14. CashCap (2022) Experiences Linking CVA with Social Protection. CashCap; IPC-IG (2022) SocialProtection.Org Annual Report. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth

15. Other studies also confirmed that COVID-19 led to increasing flexibility from development funders, enabling repurposing for humanitarian action, see Lawson-McDowall, J. and McCormack, R. (2021). The Use of Cash Assistance in the Covid-19 Humanitarian Response: Accelerating Trends and Missed Opportunities. Disasters, 45 (S1), S216–S239.

16. The Mid Term Review of BASIC highlights the results that these facilities have achieved (Maunder, N., McDonnell- Lenoach, V., Plank, G., Moore, N. and Begault, L. (2022). Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC) Performance Evaluation. Midline Report. A report by Integrity Research and Consultancy).

17. Also in The Mid Term Review of BASIC highlights the results that these facilities have achieved. Maunder, N., McDonnell- Lenoach, V., Plank, G., Moore, N. and Begault, L. (2022). Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC) Performance Evaluation. Midline Report. A report by Integrity Research and Consultancy; and Lawson-McDowall, J. and McCormack, R. (2021). The Use of Cash Assistance in the Covid-19 Humanitarian Response: Accelerating Trends and Missed Opportunities. Disasters, 45 (S1), S216–S239

18. Although Switzerland and Germany have made institutional structural changes to support programming across the nexus, with SDC humanitarian and development teams now under one division, and Germany having the Transitional Development Division which focuses on the nexus (key informant interview).

19. One issue raised is the continued separation of humanitarian versus development funding instruments, operating under different rules and timeframes. Another issue, in fragile conflict-affected situations and protracted crises, is the lack of support from institutional development donor counterparts to support the transition from humanitarian aid.

20. For example, CALP’s research highlighted this was an area where progress to move from policy commitment to practice is perceived to have been more limited (CALP (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP. (2022)). In Ukraine it has been reported that while there is rhetoric on supporting linkages there has not been a clear humanitarian and development donor commitment to fund the transition of humanitarian assistance to social protection systems, or to coordinate with development counterparts to better focus humanitarian efforts on filling gaps in social protection provision (Tonea, D. and Palaciois, V. (2023) Role of Civil Society Organisations in Ukraine: Emergency Response Inside Ukraine. Thematic Paper. CALP). A study in Jordan, looking at options for alignment of humanitarian assistance for refugees with social protection, reported the same (Smith, G. (2022a) Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance to Refugees in Jordan: Programme Mid Term Review. An internal report for FCDO in Jordan, produced by HEART). The Mid Term Review of FCDO’s BASIC programme highlighted that a factor limiting development of social protection across the nexus is the continued fragmentation of donor and multilateral programming. In the evaluation, two of the four top reported priorities of donor representatives at country level were for support to move towards models and instruments for sustainable financing of emergency assistance linking with social protection (73% of survey respondents) and improving the links between their humanitarian and social protection approaches (67% of survey respondents) (Maunder, N., McDonnell- Lenoach, V., Plank, G., Moore, N. and Begault, L. (2022). Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC) Performance Evaluation. Midline Report. A report by Integrity Research and Consultancy). Meanwhile, studies by CashCap and CALP in the Latin America and Caribbean region both highlight that the current structure of humanitarian financing and staff rotations impedes the necessary policy dialogue processes to work with governments (CashCap 2022; and CALP and USAID (2022) En construcción: una revisión de las formas de coordinación entre los grupos de transferencias monetarias (GTM) y sistemas de protección social en las Américas. CALP).

21. Including Smith, G. (2021) ‘Overcoming barriers to coordinating across social protection and humanitarian assistance – building on promising practices’, Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE), DAI Global UK Ltd, United Kingdom”; CALP (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP; CashCap (2022) Experiences Linking CVA with Social Protection. CashCap; Tonea, D. and Palaciois, V. (2023) Role of Civil Society Organisations in Ukraine: Emergency Response Inside Ukraine. Thematic Paper. CALP; Bastagli, F. and Lowe, C. (2021) Social Protection Response to Covid-19 and Beyond: Emerging evidence and learning for future crises. Working Paper 614. ODI; IFRC (2021) Dignity in Action: Key Data and Learning on Cash and Voucher Assistance from Across the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement. IFRC.

22. Smith, G. (2021) ‘Overcoming barriers to coordinating across social protection and humanitarian assistance – building on promising practices’, Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE), DAI Global UK Ltd, United Kingdom”

23. CALP (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP; Tonea, D. and Palaciois, V. (2023) Role of Civil Society Organisations in Ukraine: Emergency Response Inside Ukraine. Thematic Paper. CALP; T. Byrnes. (2022) Overview of the Unified Information System of the Social Sphere (UISSS) and the eDopomoga System. Social Protection Technical Assistance, Advice and Resources Facility (STAAR). Blin, S. and Cahill Billings, N. (2022) Humanitarian Assistance and Social Protection Linkages: Strengthening Shock-responsiveness of Social Protection Systems in the Ukraine Crisis. Social Protection Technical Assistance, Advice and Resources Facility (STAAR).

24. CALP (2021) The State of the World’s Cash 2020. CALP. The EU’s guidance on ‘Social Protection Approaches across the Nexus’ describes effective collaboration and coordination as “perhaps the keystone principle for shock responsive social protection and also its biggest challenge” (in G. Smith. (2021b). Overcoming Barriers to Coordinating Across Social Protection and Humanitarian Assistance – Building on Promising Practices. SPACE).

25. CALP (2021) The State of the World’s Cash 2020. CALP. The EU’s guidance on ‘Social Protection Approaches across the Nexus’ describes effective collaboration and coordination as “perhaps the keystone principle for shock responsive social protection and also its biggest challenge” (in G. Smith. (2021b). Overcoming Barriers to Coordinating Across Social Protection and Humanitarian Assistance – Building on Promising Practices. SPACE).

26. Smith, G. (2021) ‘Overcoming barriers to coordinating across social protection and humanitarian assistance – building on promising practices’, Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE), DAI Global UK Ltd, United Kingdom.

27. CALP (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP.; IFRC (2021) Dignity in Action: Key Data and Learning on Cash and Voucher Assistance from Across the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement. IFRC; Raftree, L. (2022) Case Study: Responsible Data Sharing with Governments. CALP; G. Smith. (2022b) Assessing System Readiness for Shock Responsive Social Protection in Palestine: Summary Report of Findings and Options Analysis. A report for UNICEF Palestine. Also highlighted in FGDs.

28. For example, CashCap (2022) Experiences Linking CVA with Social Protection. CashCap; WFP (2022) Evaluation of Jordan Country Strategic Plan Evaluation 2020–2022. Centralised Evaluation Report. WFP.

29. Monitoring sustainability and government ownership is one of nine priority outcome areas for monitoring effectiveness of linking social protection and humanitarian action that is set out in a forthcoming STAAR guidance on “collective outcomes”, due to be published in 2023.

30. For example, Beazley, R., Bischler, J. and Doyle, A. (2021) Towards Shock-responsive Social Protection: Lessons from the COVID-19 Response in Six Countries. Synthesis Report. Oxford Policy Management

31. Further research on the ability of social protection systems to anticipate, absorb, accommodate, or recover from the effects of a hazardous event is recommended. Slater, R. (2022) Sustaining Existing Social Protection Programmes During Crises: What Do We Know? How Can We Know More? BASIC Research Working Paper 14. Institute of Development Studies

32. G. Smith. (2022b) Assessing System Readiness for Shock Responsive Social Protection in Palestine: Summary Report of Findings and Options Analysis. A report for UNICEF Palestine; Smith, G. (2023) Shock-responsive Social Protection in Nepal: An Assessment of Entry Points and Actions to Plan a Pilot Flood Response in the Child Sensitive Social Protection Project Zone. Save the Children Finland. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/shock-responsive-social-protection-in-nepal/; Smith, G. (2022c) WFP Cambodia Social Protection Scoping Study: Final Report. A report for WFP by the University of Wolverhampton.

33. In Lawson-McDowall, J. and McCormack, R. (2021). The Use of Cash Assistance in the Covid-19 Humanitarian Response: Accelerating Trends and Missed Opportunities. Disasters, 45 (S1), S216–S239

34. Wylde, E., Carraro, L. and Mclean, C. (2020) Understanding the Economic Impacts of COVID-19 in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Who, Where, How, and When? SPACE

35. Taken from Bastagli, F. and Lowe, C. (2021) Social Protection Response to Covid-19 and Beyond: Emerging evidence and learning for future crises. Working Paper 614. ODI; also identified in Smith, G. (2021) ‘Overcoming barriers to coordinating across social protection and humanitarian assistance – building on promising practices’, Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE), DAI Global UK Ltd, United Kingdom”; CashCap (2022) Experiences Linking CVA with Social Protection. CashCap; and Beazley, R., Bischler, J. and Doyle, A. (2021) Towards Shock-responsive Social Protection: Lessons from the COVID-19 Response in Six Countries. Synthesis Report. Oxford Policy

36. Lawson-McDowall and McCormack (2021); Bastagli and Lowe (2021); IFRC (2021); WFP (2020) Supporting National Social Protection Responses to the Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19: Outline of a WFP Offer to Governments. WFP; UNICEF (2021) Preparing Social Protection Systems for Shock Response: A Case Study of UNICEF’s Experiences in Armenia. UNICEF

37. This is a conclusion of several of the abovementioned studies and is central to the themes of USP2030. Improving the quality of routine social protection systems was also a priority identified by respondents in the BASIC Mid Term Evaluation (Maunder, N., McDonnell- Lenoach, V., Plank, G., Moore, N. and Begault, L. (2022). Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC) Performance Evaluation. Midline Report. A report by Integrity Research and Consultancy). The World Bank’s new diagnostic tool on adaptive social protection is promoting a focus on core systems and on strengthening routine social protection as well as entry points for flexing and scaling during crises.

38. Maxwell, D., Howe, P. and Fitzpatrick, M. (2023) Famine Prevention: A Landscape Report. Feinstein International Center, Tufts University.

39. For example, ILO (2020) ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work: Updated Estimates and Analysis. Third Edition. ILO.

40. Little, S., McLean, C. and Sammon, E. (2021) Covid-19 and the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) and Conditional Cash Transfers for Education (CCTE) Programmes. CALP Network.; Holmes, R. and Lowe, C. (2023) Strengthening Inclusive Social Protection Systems for Displaced Children and Their Families. ODI and UNICEF.

41. There are examples of inclusion of refugees into social protection but these are still few in number (a finding of ODI’s research project on social protection responses to forced displacement)

42. FAO Lebanon (2023) The Lebanese Farmers’ Registry at a Glance. Powerpoint Presentation for the Ministry of Agriculture in Lebanon. FAO Lebanon

43. See Smith, G. (2022a) Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance to Refugees in Jordan: Programme Mid Term Review. An internal report for FCDO in Jordan, produced by HEART.

44. For example, Holmes, R. and Lowe, C. (2023) Strengthening Inclusive Social Protection Systems for Displaced Children and Their Families. ODI and UNICEF

45. Lowe, C. and Cherrier, C. (2022) Linking Social Protection and Humanitarian Assistance: Guidance to Assess the Factors and Actors that Determine an Optimal Approach. ODI

46. STAAR FGD (GESI focal point)

47. Maunder, N., McDonnell- Lenoach, V., Plank, G., Moore, N. and Begault, L. (2022). Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC) Performance Evaluation. Midline Report. A report by Integrity Research and Consultancy

48. Slater, R. (2022) Sustaining Existing Social Protection Programmes During Crises: What Do We Know? How Can We Know More? BASIC Research Working Paper 14. Institute of Development Studies; Lawson-McDowall, J. and McCormack, R. (2021). The Use of Cash Assistance in the Covid-19 Humanitarian Response: Accelerating Trends and Missed Opportunities. Disasters, 45 (S1), S216–S239

49. Countries included Afghanistan, Armenia, Bangladesh, CAR, Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Nigeria, Palestine, Philippines, Sahel, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Uganda, Ukraine, Yemen.

50. Smith, G. (2022) Options for continuing social protection upon the onset of conflict and insecurity. A presentation of options for FCDO in Ethiopia. Social Protection Technical Assistance and Advisory Facility.

52. For example, under the FCDO STAAR Facility there are plans to develop guidance and knowledge products. The SPIAC-B working group on linking humanitarian assistance and social protection is developing a set of Common Principles to guide engagement on linkages, including in conflict settings. Meanwhile in January 2023, USAID launched a consultation process on social protection approaches in fragile and conflict-affected states.