The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Chapter 3: Locally-led Response

Summary

Key findings

- Local and international perspectives on what locally-led response means are often fundamentally different.

- There has been some progress towards locally-led response, but major change is lacking.

- Barriers to progress in locally-led CVA reflect issues in the wider system.

- The perceived tension between scaling and localizing CVA is solvable.

- Emerging models and different entry points offer new ways of working and important lessons for locally-led CVA.

Main challenges that LNAs face in scaling up CVA

Strategic debates

- Can arguments that present large-scale CVA as being in opposition to locally-led response be overcome? How can CVA models led by international actors be changed to facilitate locally-led response?

- Can international actors adapt their mindsets and ways of working to align with and support local contexts and stakeholders?

- How should funding models and mechanisms be adjusted to increase locally-led CVA?

Priority actions

- All stakeholders should continue to advocate and accelerate practical changes to CVA models and ways of working to enable a ‘locally-led first’ approach where appropriate.

- International actors should adapt, rather than expecting local actors to accommodate the requirements of international CVA structures, systems, and ways of working.

- Donors and intermediaries should increase access to CVA funding by local and national actors, making compliance requirements equitable and proportionate.

- Donors should increase quality CVA funding for local and national organizations including predictable and adequate resourcing to enable capacity development and institution building.

- INGOs and UN agencies should increase intermediary funding to local and national organizations, and facilitate locally-led CVA, with equitable sharing of overheads. Donors should ensure this happens.

- Donors and international actors should fund and support the meaningful engagement and leadership of local and national actors in CVA coordination mechanisms and policy forums.

Locally-led response

This chapter focuses mainly on non-state actors, primarily NGOs and other civil society and community-based organizations. This does not imply a definition of locally-led response which excludes governments, rather the role of governments is covered in Chapter 6 on Linkages with social protection. Equally, issues affecting the engagement of non-state actors in humanitarian CVA differ in many (but not all) respects from those affecting governments, hence the rationale for presenting much of the analysis separately.

Perspectives on and conceptualizations of localization and locally led response remain divergent

“[Key informants] saw the need to focus

on the commitment to localization overall,

which… [requires] challenging shifts in

power dynamics in aid delivery. While CVA

can certainly play a part in localization,

the overarching sense is that once a truly

localized response is genuinely enabled,

CVA will naturally follow.” (CALP (2022)

Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of

Cash and Voucher Policies)

The State of the World’s Cash report (2020) recommended that humanitarian actors should: a) recognize that progress on CVA localization means shifts in power, as well as changes to funding processes, systems, and requirements; and b) agree on clear, measurable, and shared priorities for the localization of CVA and commit to action. That report also highlighted that while the Grand Bargain commitments 1, Charter for Change 2, and work by the likes of Start Network 3 had enabled the delineation of multiple dimensions and objectives of localization, a common understanding across stakeholders was lacking 4. Despite the growing focus on this topic in the intervening period, conceptualizations of localization, and increasingly of ‘locally-led response’ (see Box 3.1) remain varied, with notable differences in perspective between local and national actors (LNA) and international actors. At the same time, CVA and localization processes have the potential to be mutually reinforcing, based on common objectives and outcomes, including empowering local communities and organizations, transforming humanitarian structures and systems, working with local financial service providers (FSPs), markets and traders, and opportunities to link with social protection systems 5.

Box 3.1: Understanding ‘localization’ and ‘locally-led response’

- Localization comprises the processes undertaken towards the goal of locally-led response. These processes are long-term and complex and could take many different pathways 6.

- Locally-led response is understood as the end-goal of these processes. While there are varying interpretations of what this constitutes, it is possible to discern several relevant dimensions that are useful in analyzing the roles of local and national actors in CVA, from participation to partnership to leadership.

- Implementation of CVA, usually as a sub-contracted partner of an international actor, without any substantial role in design, decision-making or management of resources. While this falls within the scope of localization, it is hard to argue this constitutes a locally-led response.

- Design and programmatic decision-making: leadership implies the ability to decide what type of interventions are required and allocate and manage resources accordingly. It follows that locally-led CVA implies local and national actors hold at minimum shared design, decision-making and management responsibilities. For example, USAID’s new indicator for locally-led programmes includes priority setting, design, partnership formation, implementation, and defining and measuring results 7.

- Coordination and policy: relating to both implementation and decision-making, but in terms of setting standards and influencing CVA at a strategic and policy level, at response/national and/or regional and global levels. This has dimensions both of participation and inclusivity8, and the ability to take on leadership roles, for example chairing/co-chairing cash working groups (CWGs).

Source – Authors and CashCap/Zebs technical support (June 2023) Donor Cash Forum Localization Primer

Different groups define ‘local’ to include a wide range of actors, including local and national governments 9, local and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil society organizations (CSOs), community-led organizations, and communities themselves 10. Local financial service providers (FSPs) and other private sector stakeholders involved in delivering or facilitating payment solutions and transactions are also critical to CVA, including in their potential to facilitate financial inclusion (see Chapter 8 on CVA design for more on financial inclusion). The tension between supporting local FSPs and implementers’ efforts to secure global payment solutions by using aggregators is explored more in Chapter 7 on Data and digitalization.

There are fundamental disparities between local and international perspectives on what locally-led response means in practice.

This reflects the extent to which perspective and context will help shape definitions both of what is ‘local’ and associated objectives for locally-led response. Table 3.1, an example of stakeholder perspectives in the MENA region, illustrates these differences. Local actors have expressed a broad vision for locally-led response, including objectives of achieving independence, being able to take over from international actors, and forging their own partnerships with others. The objectives and motivations of the surveyed international actors in MENA, meanwhile, tend to be more limited and/or instrumentalize the role of local actors.

Table 3.1: Example from MENA region of the differing perspectives of local and international actors on who is ‘local’, and the objectives and motivations for locally-led response 11

| Respondent type | Defining ‘local actor’ | Perceived objective | Motivations |

| Local actors | Local NGOs Community-based organizations |

Power to design, implement, manage and coordinate CVA independently of international organizations. Replace international organizations. Partner with other local actors including government, private sector, and CSOs |

Increase equality between local and international NGOs. Enhance programme quality. |

| International organizations and consortia | Local NGOs Red Cross Red Crescent (RCRC) National Societies Local employees of international organizations |

Partner with local NGOs. ‘Empower’ local NGOs |

Recognize the value of locally-led response and the general push to increase it. Access to hard-to-reach communities/areas. Enhance programme quality. |

| Donors | National governments Local NGOs |

Integrate parallel social assistance systems for both refugees and host communities. | Sustainability. Reduce cost of assistance to refugees. Adopt a nexus approach by transitioning away from humanitarian approaches and funding streams. Enhance resilience. |

When organizations talk about localization, they usually start with ways of working, rather than defining what it is they are aiming to achieve 12.International actors’ most common framing of localization, reflected in multiple KIIs, is in terms of partnership. Localization strategies can have varied objectives, with partnership formulated both as a goal and/or as a means of achieving further goals. For example, organizations including IFRC, CRS and Oxfam have CVA policies which aim to enable local partners to ultimately lead CVA responses 13. On the other hand, there was a near consensus amongst key informants that referred to the UN’s approach, including some working with UN agencies, that their approach to localization to date has been oriented more toward a goal of ongoing collaboration, and less towards enabling local leadership.

“Locally-led’ isn’t defined yet and this

is problematic. With cash, its weirdly

interpreted as being about how

international actors fund national

NGOs, missing out the direct support,

and the government/local authorities.”

(Independent Consultant)

Whether and to what extent national governments’ programming should be considered ‘locally-led’ is the subject of debate, reflected in KIIs and elsewhere 14. Some caution against conflating ‘national government’ – as an inherently centralizing force – with ‘local’ and the grassroots nature and diversity this implies. Others consider national governments to be a core element of locally-led response, acknowledging that the form of government involved will impact the type of engagement that is possible. As highlighted above, power and politics can influence the framing of conceptions and priorities for localization. One key informant argued that governments have greater potential than civil society to fundamentally change the status quo for international actors.

There has been some progress, but major change is still missing

Overall, there is a perception of some, limited progress towards locally-led response. Judged against the collective commitments and targets of the Grand Bargain, the pace of change has been very slow, although there is clearer evidence of progress in some areas in the last couple of years 15. The same view holds amongst CVA practitioners, with a general assessment of ‘slow and patchy’ progress, while consistently recognizing the central importance of localizing humanitarian response 13.

Graph 3.1

In humanitarian discourse and policy, there has been a notable increase in focus on localization over the past few years, which brings with it a sense of momentum. There is also evidence of perceived progress with regards to localizing CVA, with 58% of survey respondents agreeing that since 2019 national organizations have increasingly been taking on leadership roles in the design and implementation of CVA, with only 21% disagreeing (see Graph 3.1). Respondents from governments (71%), Red Cross Red Crescent Movement (67%) and national NGOs (61%) were the most likely to agree; donors were the only group where a minority (27%) agreed that national organizations have increased their leadership in CVA. This is also reflected in practice and although ‘implementing partner’ remains the predominant model for local actor engagement in CVA, there are varied and increasing examples of local participation, and leadership in some cases.

Several key factors, each reflecting progress and challenges, are driving the increasing focus on locally-led response.

- Key factor: COVID-19.

In the early stages of the pandemic, there was optimism that it might prove to be a catalyst for genuine progress towards locally-led response 17. With major limitations on the movement and access of international actors, the central role of local organizations in delivering international humanitarian aid was in the spotlight. Key informants and others sense that the pandemic helped shift the narrative and impetus regarding localization, but it is regarded as a missed opportunity overall. The extent to which the pandemic response constituted a significant transfer of risk to local responders, rather than a genuine effort to support locally-led response, has also been raised 18. The verdict from local actors is that despite their work and the capacities demonstrated, it “has not positively affected prevailing power dynamics or how these are fundamentally shaped by control of and access to funding”19. - Key factor: Contextual realities and emerging roles.

New and ongoing responses in conflict-affected regions with constrained or restricted access for international organisations continue to highlight the critical role of local actors in reaching communities 20. Since 2022, the Ukraine and associated regional response have generated a lot of discussion on locally-led response. While access is one dimension, the fact of humanitarian response in contexts with highly developed civil societies and governmental social protection systems increased focus on the opportunities and imperative for enabling more local response. However, multiple studies throughout the response have repeatedly highlighted systemic failures and missed opportunities21. Equally, in the Syria/Türkiye earthquake response it was also noted that – despite the leading role of local groups – institutional funding was almost all being directed to international agencies 22 . - Key factor: Policies and commitments.

Multiple organizations, including INGOs, Red Cross Red Crescent Movement, UN Agencies, and donors, have developed or updated localization policies. For some, localization is a core element of their overall strategy; some organizations have also incorporated locally-led response as an objective within their CVA policies 23. There are also examples of new collective commitments and action, including the Pledge for Change 24, and the inclusion of locally-led response as a central component of the Collaborative Cash Delivery Network’s (CCD) new strategy.

Several key informants, including other donors, remarked on the positive impact of USAID’s commitments and leadership since 2021 25, including the target of 25% direct funding to local organizations by 2025. However, there may be the need to temper expectations on the feasibility of achieving this target, due to factors such as managing associated bureaucratic loads 26. USAID’s 2022 progress report noted 10.2% of direct funding to local actors across all portfolios (development and humanitarian), up from 8.1% in 2020. Disaggregated analysis shows, however, that USAID’s direct funding for local organizations delivering humanitarian assistance fell as a percentage of this total from 2% in 2020 to 1% in 2022 27. USAID attributed this relative drop to the substantial increase in overall funding to address the global food crisis in 2022; this enabled a significant scale up in major humanitarian assistance pipelines, many of which are delivered by larger international agencies, including the UN. Recent analysis underscores the importance of ensuring metrics for tracking localization efforts are accurately aligned with agreed definitions of what constitutes ‘local’, with the potential for notable distortions if this is not done. 28 29

“Regarding commitments to localize aid,

we’re still waiting for significant results

or impacts. It is unfortunate that results

couldn’t be achieved within six years (since

the Grand Bargain).” (Key informant)

Within the Grand Bargain, there has been success in engaging LNAs at the global level 30. This includes the endorsement of a new model for cash coordination, developed through a Grand Bargain caucus, that stipulates one of the CWG co-chairs will, where possible, be a local actor. While this has been welcomed, the identification and commitment of financial resources that would enable local actors to effectively take on these roles is still pending (see Chapter 4 on Cash coordination for more). Reflecting on the influence of the Grand Bargain, one key informant noted successes on a policy level, and ‘even perhaps the beginnings of the cultural level’ but concluded that local organizations, ‘are still waiting for the result level’. The apparent gap between policy and practice is evidenced, for example, in the perspectives of local actors in MENA who expressed scepticism that ‘any policies are prioritizing local leadership in the implementation of CVA’ 31. The Grand Bargain Localization caucus recently called on signatories to develop roadmaps, by the end of 2023, on how and when they will reach the 25% target.

- Key factor: A growing evidence base and emerging evidence of the benefits of locally-led response. While not systematically documented or consolidated, there are an increasing number of examples of locally-led CVA. For example, in Colombia Fundación Halü Bienestar Humano worked with partners to provide cash for vital documentation for populations on the move from crisis in neighbouring Venezuela; and in South Sudan, Titi Foundation worked in close collaboration with community groups, lowering operational costs and increasing the efficiency and coverage of a locally designed CVA programme 32. There are also examples of organizations such as Ma’an Development in Palestine and Dhaka Ahsania Mission (DAM) in Bangladesh who have built substantial internal CVA capacities, including through working with international partners and engaging in CWGs. The increased focus on localization policy and practice has generated the development of research and guidance, including a limited amount considering CVA 33. While documenting learning and key blockages and opportunities, research is also helping to identify what the benefits of locally-led response could be in addressing some of the critical challenges facing a strained humanitarian system, including potential efficiency gains 34.

Barriers to progress are crystallizing around a few critical issues

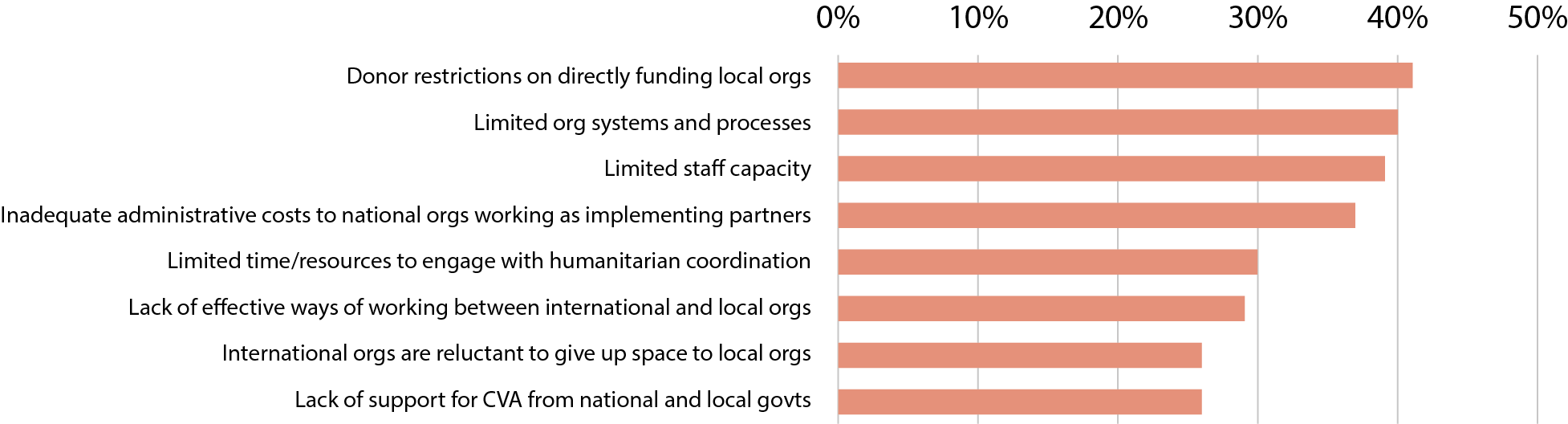

Graph 3.2: Main challenges that local and national actors face in scaling up CVA

Our interviews with key informants and focus groups, including, critically, all of those with local actors, highlighted three key interrelated and reinforcing constraints that continue to limit progress towards locally-led CVA – namely funding, capacities, and lack of meaningful engagement.

These opinions are backed up with findings in numerous studies 35 and are matched by the responses in our survey. These barriers inhibit progress in almost all recognized dimensions of locally-led humanitarian action 36

Lack of direct funding for local actors

Data shows the proportion of funding to local actors is in decline, despite Grand Bargain commitments made in 2016 for 25% of available funding to be channelled ‘as directly as possible’ to local organizations by 2020. In 2022, direct funding to local actors accounted for only 1.2% of overall assistance, the lowest share since 2018; of this, only 20% went to local or national NGOs. Combined direct and indirect funding to local and national actors 37fell from 2.7% of overall assistance in 2021 to 2.1% in 2022 38. Survey respondents (particularly noted by national NGOs) frequently cited continued lack of access to funding as a barrier to achieving more locally-led CVA – it was also the most frequent challenge highlighted in interviews. Key informants identified three factors contributing to this, which are also highlighted in various studies 39:

Limitations in funding instruments

“We tried to participate twice in the

Emergency Response Fund but we

never received any funds. It is still with

international organizations. So, this last

time we did not participate because I did

not really see the value. We don´t receive

any feedback about the reason why we

were not included and how we could

access the funds.” (ECOWEB)

Key informants noted funding regulations that restrict key CVA donors (e.g., ECHO, GFFO) from directly funding local actors. They also commented on the lack of funding instruments dedicated to local actors, meaning organizations effectively end up competing for funds with international agencies. Key informants from local organizations reflected that given the application processes, they are not on a level playing field, even for mechanisms to which they theoretically have equal access such as the UN Country Based Pooled Funds (CBPFs). CBPFs are seen as an important mechanism to channel more to LNAs, particularly where donor regulations may restrict direct bilateral funding. The share of funding to LNAs from CBPFs has gradually increased, to 28% in 2022, up from 24% in 2017, although to date, CVA has generally only made up a small percentage of CBPF-funded projects. However, as a proportion of international humanitarian assistance, funding to CBPFs has been decreasing, from 7.6% in 2019 to 5.4% in 2022. Overall, 79% of international funding to local and national NGOs for which tracking data is available passed through at least one intermediary (primarily pooled funds)40. Research indicates that funding via intermediaries limits the ability of local actors to influence donors, or access flexible, multiyear funding 41. Compliance for local organizations is also compounded when funding instruments aren’t direct as intermediary funds include donor AND international organization requirements.

Due diligence and risk appetite

“Funders’ misapprehension of risk, in turn,

drives restrictive and overly burdensome

procurement, compliance, and financing

requirements that then shut out new and

local partners by creating barriers that

are simply too high to overcome.”

Humentum (2023)

A key barrier to local actors accessing direct funding for CVA are donors’ compliance requirements. This is also an issue for accessing pass-through/indirect funding via intermediaries. Key informants, both local and international, commented that the bar for compliance is set too high for local actors and that their ability to absorb fiduciary and operational risks on CVA will be scored lower if compared directly to international agencies. These are, fundamentally, issues of trust, and models of risk and accountability oriented primarily around donor interests. Current conceptions of risk also don’t usually take account of the risk to effectiveness where programming is not locally led 42. Within current ways of working, risk is generally framed in terms of risk transfer towards local actors, rather than an approach founded on risk sharing and the value of local action, that could facilitate better mutual partnerships and accountability 43.

Donor capacities/desire for efficiency

“A lot of donors give [CVA] money to UN

agencies because it’s the most convenient

thing to do.” (Key informant)

Key informants highlighted that the trend among donors to direct CVA through fewer, larger contracts inevitably favours international organizations and eliminates the possibility of funding multiple smaller local actors. The primary driver of these types of operational models has been to achieve greater efficiencies, although as has been highlighted in previous State of the World’s Cash reports, the need to balance this with other factors of quality programming (which include localization) is compelling. In addition, it has been estimated that ‘local intermediaries could deliver programming that is 32% more cost-efficient than international intermediaries, by stripping out inflated international overhead and salary costs’ 44. See the section below on the tensions between scaling and localizing CVA.

Capacities of local actors, and associated resourcing

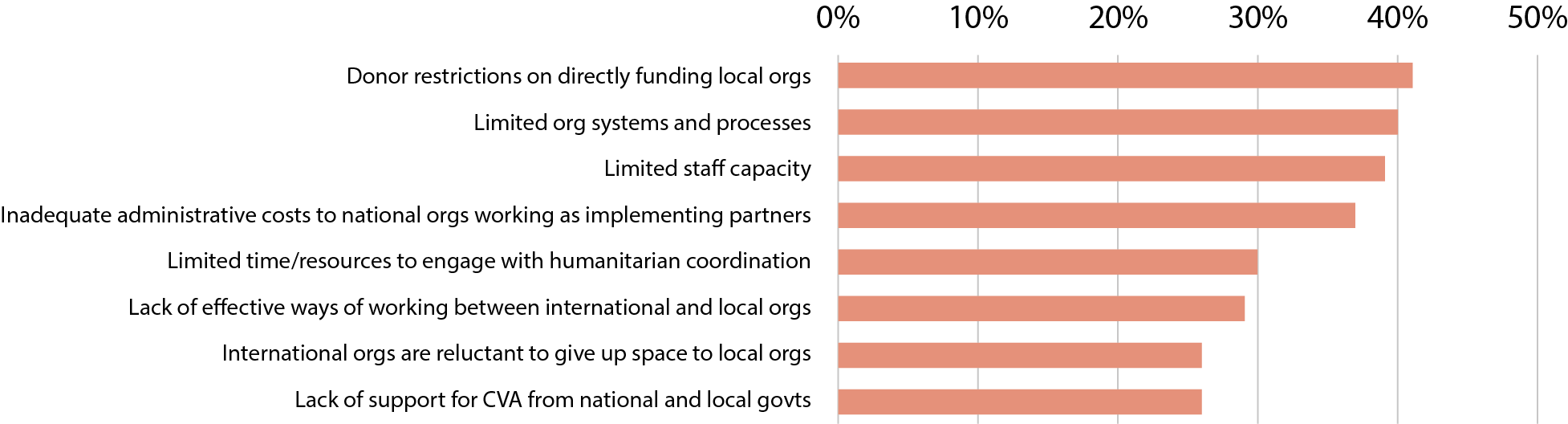

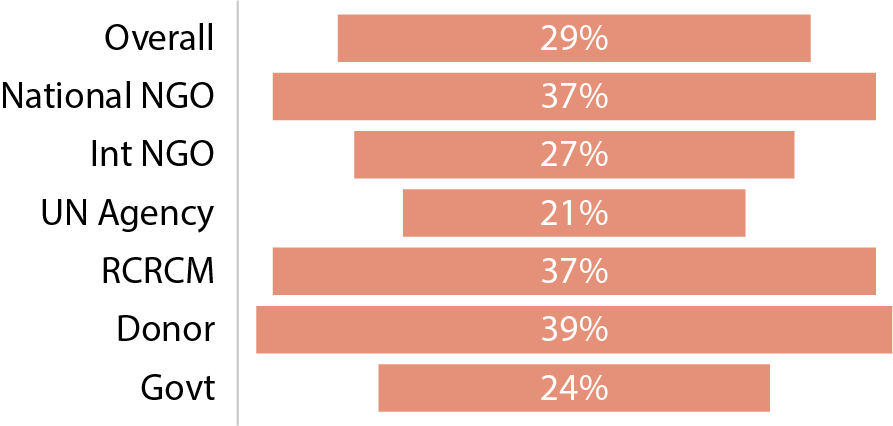

Graph 3.3

Graph 3.4

In our survey, two of the top three most frequently cited barriers to locally-led CVA relate to challenges with operational and technical capacities of local actors to manage CVA (see Graph 3.2). There are notable disparities in views between different stakeholders, with international organizations considering capacity limitations a more significant challenge than national NGOs (see Graphs 3.3 and 3.4). Several key informants considered that this reflected a lack of trust in local actors’ abilities and that concerns about capacities to handle risk are based on assumptions rather than evidence (also highlighted in recent publications 45).

Resourcing, overheads, and the circular challenge of capacity development.

Many key informants pointed to donors’ and international agencies’ lack of investment in capacity building for local CVA actors. This is on multiple levels, including a lack of technical training tailored to their needs 46(see more in Chapter 5 on Preparedness and capacity), but also, particularly, a lack of resourcing for the requisite operational systems and processes. Limited resourcing contributes to the related problem of staff retention for local organizations, due to the salary disparities with international agencies, which several key informants cited as a major challenge to maintain capacity in the medium- to longer-term. Several local actors also noted that limited staffing and resourcing is a critical barrier to engagement in coordination forums (see the earlier point on resourcing for local actors in CWGs). In our survey this was the fifth most cited barrier to locally-led CVA.

% respondents who consider inadequate admin costs to national implementing partner orgs a main challenge

% respondents that consider limited time/resources to engage with humanitarian coordination a major challenge

Approaches to funding that tend to be

short-term, ad hoc, and have minimal

support costs also do not enable local

partners to build the capacity and systems

necessary for a quality CVA response”.

Lawson-McDowall and McCormack

(2021)

Key informants criticized international (especially UN) agencies for not passing on an equitable share of administrative budgets to local partners. They commented that this perpetuates a circular problem, with donors and international actors citing due diligence concerns on the one hand, but not providing resources to enable local actors to make the necessary investments in systems to enhance compliance. Several studies published since 2019 comment on the same 47. There is, however, growing momentum to address the issue of overheads. At the end of 2022, the IASC published guidance on provision of overheads to local partners 48. In combination with the political push in the Grand Bargain, these processes are seen as having the potential to be effective in driving change in policy and practice 49.

Lack of meaningful engagement

“We need to start that process of trusting

local organizations and that’s I think where

a lot of the barriers are.” (Key Informant)

% respondents who consider a lack of effective ways of working between international and national orgs to be a main challenge

% respondents who consider the reluctance of international orgs to give up space to be a main challenge

Key informants commented on the nature of local actors’ engagement to date in CVA. Responses highlighted a big disconnect between how local actors expect to participate and the realities of how they are involved by international agencies in practice. In general, international organizations are perceived to retain decision-making power, with the role of local counterparts limited to that of a sub-contracted implementing partner. There is perceived to be limited involvement of local actors in strategic decision-making and leadership roles in CVA.

Key informants commented that ingrained organizational cultures and mindsets contributed to this, with limited trust, or value, placed in national actors’ abilities among the international humanitarian community. Many also raised concerns that international actors’ self-interest is limiting the transfer of power and influence, as it has direct implications for the future resourcing and roles of these organizations in a competitive funding landscape. Survey respondents also frequently highlighted this barrier – with noticeable variation in perceptions of international (especially UN) agencies compared to national organizations and donors.

Key informants welcomed the inclusion of organizations representing local actors in the new Cash Advisory Group (CAG – see Chapter 4 on Cash coordination) to address the limited engagement of local actors in cash coordination 50. Though it remains to be seen how well the group manages different mindsets, interests and power dynamics to effect meaningful involvement.

Finally, reporting and tracking systems for CVA remain geared towards the requirements and interests of international actors and don’t effectively capture local actors’ contributions. This is particularly the case where local organizations act as implementing partners for a range of programme activities, but cash transfers are provided via an international organization (with the value of these passing through their accounts). This invisibility of local actors’ contributions can also perpetuate a narrative that underplays the existing value added of local actors in CVA delivery (see Chapter 2 on CVA volume and growth).

A solvable tension between scaling and localizing CVA

In CALP’s recent study on the CVA policy landscape, key informants frequently cited a tension between locally-led response and scaling CVA 51. This tension has also been highlighted elsewhere, including previous State of the World’s Cash reports, and can imply that the goal of locally-led response is local actors’ delivering large-scale CVA. Perceptions about the capacity of local organizations to manage large-scale responses and funding can also serve as a significant drawback to contracting and funding them 52. However, the apparent contradiction between localizing and increasing CVA needs to be unpacked.

The discourse on the tensions of locally-led CVA and scale sometimes wrongly implies that there are no examples of local actors providing large-scale CVA. Red Cross Red Crescent National Societies have programmed large-scale cash assistance, with the Turkish Red Crescent and the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN) being perhaps the most obvious example. There are also examples of national NGOs delivering large-scale cash assistance. For example, according to submissions to CALP and Development Initiative’s annual CVA volume exercise, Karkara – a national NGO in Niger – has consistently programmed over US$10 million in CVA per year between 2020 and 2022. Furthermore, if government-administered CVA is considered, there are examples such as the Pakistan Government’s rapid distribution of over US$300 million via a social protection programme in response to the 2022 floods, which dwarfed any other humanitarian CVA intervention in that response 53.

Some key informants reflected on the need to explore different approaches or models for at-scale programming, and the roles of local organizations within these. If, for example, large-scale locally-led CVA replicates current models favouring a few actors delivering to large numbers of people (but with (a small number) of LNAs replacing international organizations), this could pose a major challenge in at least the short- to medium-term with regards to operational capacities. It is also worth remembering that large-scale operational models such as these can also mask the visibility of multiple implementing partners, which already includes many local organizations. Several key informants emphasized the fact that at-scale doesn’t need to replicate current models, outlining alternative options based on networks and groups of local organizations working together (see the section on accelerator models below for more on how these approaches are being tested in practice). The research also highlighted that many key factors generating the tension between locally-led response and cash at-scale relate to funding structures; while changing these may involve very difficult, lengthy, and complex processes, as one key informant noted, this makes it more an issue of political will and not necessarily impossible.

A range of potential roles and entry points for locally-led CVA

In talking about the challenges of locally-led CVA at large-scale, several key informants reflected on the fact that in many cases this may not even be the role individual organizations want to play. There are multiple ways to lead, participate and add value, including through complementing or enhancing inclusion within large-scale cash responses. Across the research a diverse range of potential roles for local actors were identified, with different entry points and multiple pathways to, and models of, locally-led CVA. Many of these could co-exist within a given context or response. The following attempts to summarize the key possibilities, drawing on key informant feedback and secondary research:

| Table 3.2: Localizing CVA – Summary of potential roles and models |

| Type of intervention / area of engagement | Potential models/composition | Comments |

| At-scale – Local actors implementing the whole CVA delivery chain |

|

|

| Smaller scale – Local actors implementing the whole CVA delivery chain |

|

|

| Specialized functions within or complementing the CVA delivery chain – e.g., assessment, outreach/inclusion, monitoring, accountability, protection |

|

|

| Complementary assistance or services e.g., cash plus |

|

|

| Social protection – specialized roles within or complementing the delivery chain e.g., outreach/inclusion, accountability, monitoring |

|

|

| Advisory and advocacy roles to humanitarian response planning and coordination (local needs, reach, targeting, design) |

|

|

Several key informants mentioned the need for caution – local actors with links to communities and excluded groups can certainly be an entry point for achieving more people-centred CVA, but being ‘locally-led’ does not automatically achieve more accountable or inclusive programming. Locally-led CVA can be people-centred only when it factors the perspectives of communities, including relating to existing relationships and norms, and ensures transparency and accountability. There is no robust evidence regarding affected people’s perspectives on the implications of localization and their preferences on who provides aid. Existing research from Ground Truth Solutions includes some examples of communities preferring assistance from local organizations, and others where communities can feel more comfortable with and trust international aid providers because they are more removed from community dynamics 54.

Innovative approaches to localizing CVA

Since 2020, various organizations have committed to localizing humanitarian assistance, including CVA. Key informants shared examples of approaches that are being tested, or scaled up, including 55:

- Share Trust’s Local Coalition Accelerator, which aims to support progress in locally-led response, including CVA, in Uganda, Nigeria and Bangladesh (see Box 3.2).

- IFRC’s efforts to institutionalize cash preparedness within National Societies, contributing to over 60 societies being cash ready (able and likely to provide timely, scalable, and accountable CVA) and for the Movement to become the second largest humanitarian distributor of CVA in the world, now providing around 20% of the total humanitarian cash assistance (see Chapter 5 on Preparedness and capacity for details)56.

- NEAR Network’s Change Fund, which has been piloted with the aim of channeling higher volumes of funding to members through a new mechanism with a different kind of governance, overseen by other local/national organizations. It aims to provide funding that is simpler and more accessible, with projects funded through the pilot having included CVA (see Box 3.2 below).

- The Collaborative Cash Delivery Network (CCD) is piloting a range of localization initiatives for more effective inclusion of local and national organizations, tailored to response context and demands. These include engaging local actors as CVA consortium members (e.g., Colombia); formation of a localization task team in South Sudan; and piloting due diligence passporting in the Türkiye/Syria earthquake response to simplify and harmonize processes; and piloting different localization models across the Ukraine/regional response (see Box 3.2 below).

- Start Network has developed a new, tiered due diligence model, with the objective of overcoming typical due diligence requirements to enable more funding to reach local organizations. Building on this, local organizations are being funded via the Start Fund (including for CVA) to test the due diligence model in practice in terms of assumptions around risk, trust, and effectiveness (see Box 3.2 below).

- Group cash transfers have been the subject of increased interest in recent years, with guidance and tools published in 202157. They focus on the efforts of community-based organizations, including in their roles as first responders, with an objective of transferring decision-making power to affected communities. Group Cash Transfers are usually relatively small (up to a maximum of around US$7,000), and while they can be used as a standalone approach, evidence indicates they are most effective when implemented to complement other activities, including regular CVA targeted households. The potential role of group cash transfers as part of anticipatory action is also an area of increasing interest. Learning from these experiences provides some common lessons which could offer ways of overcoming some of the barriers to progress (Box 3.2).

- CashCap has introduced localization as a core component of its new strategy, using different mechanisms to strengthen capacity and reinforce the roles of local organizations. For example, through embedding experts in local and national organizations (e.g., Syria, Ukraine Red Cross Society), and working to reinforce the role of local organizations in cash coordination (e.g., Northwest Syria CWG).

Learning from these experiences provides some common lessons which could offer ways of overcoming some of the barriers to progress (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2: Promising practices for overcoming barriers to locally-led CVA

Aggregator functions to overcome funding barriers and enhance visibility: Share Trust’s Local Accelerator initiative brings together and consolidates multiple LNGOs into joint platforms, with shared governance arrangements. The intention is to overcome due diligence issues and donor aversion to managing multiple small contracts, thus increasing direct access to bilateral funding. As part of its efforts to enhance the cash preparedness of national societies, IFRC also adopted a similar aggregation approach, convening 25 smaller National Societies (with 20 focusing on CVA preparedness) to collectively apply for and access capacity strengthening funding from ECHO. Such local coalitions can also help to make local actors more visible to international actors for other partnerships.

More equitable partnerships: Under IFRC’s approach to localizing CVA (through the roll out of the Movement’s CVA Preparedness Framework), the responsibility for management of CVA programmes is being centred within national societies with support from donor national societies such as the British Red Cross. This has been a stepwise progression to ensure that trust and accountability are vested with the national societies, with support provided as needed through the IFRC. The IFRC is encouraging more equitable partnerships, and the transfer of resources – for staffing, and systems – to national societies. Share Trust plays a similar role in its local accelerator partnership in Uganda, where it aims to ‘flip the model’ through mentoring and system building over three years. CCD’s experiences highlight similar potential with the consortia approach, where national NGOs can be engaged as members alongside international partners. Risk sharing with international partners means they can be exposed to donors’ compliance requirements without assuming unmanageable risk, and gradually assume greater roles and responsibilities once trust is built and experience grows.

Facilitate access to funding through simplified processes and requirements: With due diligence processes consistently identified as a major barrier to increasing locally-led response, efforts to overcome this are critical. The CCD has been piloting due diligence passporting (accepting other agencies’ due diligence checks) and harmonization (agencies work together to combine their due diligence processes and agree on a common format) in the Türkiye/Syria earthquake response to help save time and resources for local and international organizations in forming partnerships 58.

Start Network’s due diligence model, 59 developed over the last few years, uses tiers for compliance, rather than risk-based profiles, rooted in principles of equity and proportionality (i.e., it’s not proportional to apply the same requirements for a small organization and one with a turnover of hundreds of millions of dollars). Eighty-four percent (84%) of the organizations that Start Network has been able to bring into the network via the new due diligence model would have failed their previous (more standard) due diligence requirements. They are also working to decentralize due diligence assessment services to the level of country of operation.

New funding models designed to enable direct funding of local organizations: In order to test their new due diligence framework and challenge assumptions regarding risk, Start Network has been funding newly accepted members via the Start Fund. This has required close working with their donors, including to gradually increase the available funding ceiling (e.g., up to 60,000 GBP). With a focus on generating evidence through independent monitoring, the supported responses (which have included a good amount of CVA) have commonly achieved up to a 99% satisfaction level from affected communities. In 2021, local and national actors directly or indirectly received 20% (US$4 million) of the US$20 million Start Fund disbursed 60.

NEAR’s Change Fund (piloted in 2022) is designed to be simple and accessible (e.g., applications can be in any language), with a governance structure and application review process managed by local organizations for the provision of small grants. To date, US$1.5 million has been disbursed to members 61. CVA was a regular component of applications under the pilot, largely from local consortia, with the flexibility and trust built into the fund facilitating this. Evaluations have indicated a high level of success and impact.

Forums engaging local actors as capacity builders and supporting peer-to-peer learning: In this phase of IFRC’s cash preparedness journey, the internal reference group that supports the IFRC Cash Hub has been expanded. Seven RCRC societies – Nepal, Zimbabwe, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Kenya, and Turkey – are now contributing to inform future development of guidance and tools. In 2021, IFRC also introduced regional communities of practice, bringing together the more advanced, cash-ready national societies to support and mentor other societies in their region. IFRC is funding a 12-month technical learning role to generate learning on how these communities of practice add value to the Federation’s CVA localization efforts.

Umbrella bodies providing cost-effective representation and voice: In Palestine, one member organization (Ma’an Center for Development) of the PNGO network with experience in CVA was elected to represent local civil society in the Gaza CWG. This offers potential to circumvent the challenge of resource constraints limiting participation in coordination forums, enabling local CVA actors to stay abreast of and make contributions to policy dialogue.

Source: Compiled from published reports plus findings from KIIs 62.

Implications for the future: Areas for strategic debate and priority actions

Areas for strategic debate

- Are the tensions between locally-led CVA and large-scale response real? Whether implicit or explicit, debates on locally-led CVA can equate success with implementing large-scale (in terms of volume) responses; often framed in a way that assumes current internationally-led operational models as the approach for local organizations to replicate. This seems to be at the root of the regularly cited tensions between localization and CVA as it has evolved to date. However, emerging examples and thinking indicate a range of different options for locally-led CVA, including models for large-scale responses that can achieve the goal of assisting many people, but that may be quite different to current CVA models (e.g., see examples of aggregator and local accelerator models outlined above). A framing for multiple and varied manifestations of ‘at-scale CVA’ would allow context and the types and numbers of local actors involved to inform it, including those for whom implementing very large-scale programming themselves may be neither feasible nor desirable. This does not imply that current models are ineffective. Rather, that situating locally-led CVA as being in conflict to large-scale programming appears counterproductive, particularly if presented as something somehow inevitable or immovable. Facilitating the changes needed to enable different, locally-led CVA models to develop, is in many respects about acts of political will and the transfer of power, to amend funding and other institutional structures underpinning programming.

- How does the CVA model need to change to facilitate locally-led response? When asked about future actions and debates regarding locally-led CVA, some key informants framed their response in terms of ‘flipping the model’. Local and national actors are still most often relegated to implementing CVA programmes that international actors design and manage, rather than leading the substance of designing interventions and determining the allocation of resources. Inverting roles and relationships would entail changing funding flows, so they are channeled to local and national actors and who could, if they wish, sub-contract international partners to provide services. Such a change would involve lengthy transitional processes and approaches, with substantial commitment and willingness to change from all stakeholders.

- Whose mindsets and practices need to change? The frequent focus in localization is on how local stakeholders need to adapt or develop capacities to accommodate and engage with the structures and demands of international humanitarian systems and actors. However, there is a compelling argument to flip this paradigm, with greater emphasis on the imperative for international actors to adapt to local stakeholder contexts and capacities. This could include, for example, working with different types of organizations beyond just local humanitarian organizations (such as cooperatives and microfinance institutions) who may take on different roles or execute things in different ways. In practice, this will likely be a two-way process and involve compromise, but there is a need for common commitments on all sides to realize it.

- Recognizing the mutual and reinforcing relationships between funding, capacity, and trust. Without necessary investments, including equitable sharing and provision of overheads, the issue of requisite local CVA capacities will continue to go in circles. This applies both to programming, and the ability of local and national actors to effectively undertake leadership roles within response and global level CVA policy and coordination forums. Building capacity necessarily requires being able to accumulate experience. Being able to manage risk is a key element of facilitating this space to learn through programming. In the short- to medium-term at least, this may require international organizations to be willing to take on risks (e.g., in terms of financial management) on behalf of local and national partners.

- How can funding models and mechanisms be adjusted to increase locally-led CVA? This includes exploring what donors can do in the short- to medium-term to increase direct funding – assuming more fundamental shifts will take longer. There is an argument to identify opportunities to ‘build trust by doing’ (e.g., work by Start Network and NEAR), but this presents challenges to current ways of working, particularly regarding due diligence and compliance. Necessarily, making changes will involve different approaches to how risk is defined, managed, and shared.

Priority actions

In relation to the strategic debates above and other key findings in this chapter, the following are recommended as priority actions for stakeholders.

- Local, national, and international stakeholders should advocate for an ongoing transition to new paradigms of programming to enable a ‘locally-led first’ approach where appropriate, and facilitate structures and ways of working that are adapted to the strengths of local and national responders.

- International actors should adapt mindsets, strategies and operations to local contexts and capacities, rather than framing localization processes around local actors accommodating and adapting to the requirements of international CVA structures, systems, and ways of working.

- Donors and intermediaries should take steps to improve access to funding by local and national actors. For example, developing equitable and proportionate compliance requirements that build on examples of effective simplified due diligence and passporting; and adopting a risk-sharing approach to programming, with a willingness to absorb risks on behalf of local partners as they build requisite institutional capacities and accumulate CVA experience.

- Donors should explore options for increasing CVA funding to local and national organizations, also recognizing that addressing capacity gaps requires predictable and adequate resourcing. Key strategies include addressing related internal regulations, contributing more to relevant funding mechanisms (while evaluating application processes and prioritizations) – e.g., pooled funds, ‘aggregator’ funding for collective locally-led action, considering a dedicated ‘Transition Fund’ for building respective capacities of LNAs, and exploring and/or developing new funding mechanisms.

- INGOs and UN agencies should increase intermediary CVA funding to local and national organizations, based on partnership strategies that facilitate locally-led programming, including equitable sharing of administrative overheads. Donors should put in place policies to incentivize and ensure this.

- Donors and international partners should fund, encourage, and facilitate the meaningful engagement and leadership of local and national actors in CVA coordination mechanisms and policy forums.

3. E.g., Start Network’s Disasters and Emergencies Preparedness Programme (DEPP

4. CALP (2020) State of the World’s Cash 2020. CALP

5. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement (2021) Strengthening locally led humanitarian action through cash preparedness. Cash Hub/ NORCAP

6. HAG, CoLAB & GLOW (2023) A pathway to localisation impact: Laying the foundations. Melbourne: HAG

7. USAID (2023) Moving toward a model of locally led development – FY 2022 localisation progress report

8. The frequently limited participation of local and national actors in coordination and policy structures, and the associated inclusivity challenges, have been outlined in the State of the World’s Cash (2020) and elsewhere.

9. This chapter focuses mainly on non-state actors, primarily NGOs and other civil society and community-based organizations, but this does not imply a definition of locally-led response excluding governments. The role of governments is covered primarily in Chapter 6 on Linkages with social protection, while the issues affecting the engagement of non-state actors in humanitarian CVA differ in many (but not all) respects from those affecting governments

10. Baguios, A., King, M., Martins, A. and Pinnington, R. (2021) Are we there yet? Localisation as the journey towards locally led practice: models, approaches and challenges. ODI Report. London: ODI

11. Table sourced from: Vooris, E., Maughan, C. Qasmieh, S. (2023) Locally-Led Responses to Cash and Voucher Assistance in the Middle East and North Africa – Barriers, progress and opportunities. CALP

12. HAG, CoLAB and GLOW (2023) A pathway to localisation impact: Laying the foundations. Melbourne: HAG

13. Kreidler, C. and Taylor, G. (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP Network.

14. Vooris, E., Maughan, C. and Qasmieh, S. (2023) Locally-Led Responses to Cash and Voucher Assistance in the Middle East and North Africa – Barriers, progress and opportunities. CALP.

15. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023) Grand Bargain Annual Independent Report 2022: An Independent Review. London: ODI/HPG.

16. Kreidler, C. and Taylor, G. (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP Network.

17. CALP (2020) p157

18. E.g., https://www.alnap.org/blogs/a-locally-shaped-future-for-cva; and Lawson-McDowall, J., McCormack, R. and Tholstrup, S. (2021) The Use of Cash Assistance in the Covid-19 Humanitarian Response: Accelerating trends and missed opportunities. Disasters 45 (S1): S216–39.

19. The Use of Cash Assistance in the Covid-19 Humanitarian Response: Accelerating Trends and Missed Opportunities. Disasters, 45 (S1), S216–S239

20. E.g., Humanitarian Outcomes (2022) Enabling the local response: Emerging humanitarian priorities in Ukraine March–May 2022. Humanitarian Outcomes/UK Humanitarian Innovation Lab

21. e.g., Humanitarian Outcomes (2022) Enabling the Local Response: Emerging humanitarian priorities in Ukraine March–May 2022. Humanitarian Outcomes/UK Humanitarian Innovation Lab; Tonea, D. and Palacios, V. (2023) Role of Civil Society Organisations in Ukraine – Emergency Response inside Ukraine Thematic Paper. CALP.

22. Alexander, J. (21 March 2023). Earthquake funding gap exposes larger fault lines for emergency aid sector. The New Humanitarian

23. Kreidler, C. and Taylor, G. (2022)

26. Saldinger, A. (April 27, 2023) USAID localisation goals could be hard to reach, Power says. Devex

27. USAID (2023) Moving Toward a Model of Locally Led Development: FY 2022 Localization Progress Report. USAID.

28. Publish What You Fund’s analysis found significant differences between what would be classified as funding to local partners by USAID’s measurement approach (11.1% – direct local funding, plus direct regional funding and government to government assistance) as compared to a more detailed approach they used (5.7%), which excludes locally established partners of international NGOs and companies. The implication is that if used viz their 25% target for local funding, USAID’s measurement approach would underfund local partners by US$1.43 billion per year.

29. Tilley, A. and Jenkins, E. (2023) Metrics Matter: How USAID counts “local” will have a big impact on funding for local partners. Publish What You Fund

30. Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W. and Manji, F. (2023)

31. Vooris, E., Maughan, C. and Qasmieh, S. (2023)

32. Smart, K (2020) Blog – A locally shaped future for CVA

33. See the endnotes for the full list of resources referenced in this chapter.

34. Venton, C. C. et al. (2022) Passing the buck: The Economics of Localizing International Assistance, The Share Trust.

35. Baguios, A., King, M., Martins, A. and Pinnington, R. (2021); Cabot Venton, C. (2021) Direct Support to Local Actors: Considerations for Donors. SPACE; Cabot Venton, C., et al. (2022) ShareTrust; CALP (2022) Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP; Smith, G (2021) Overcoming Barriers to Coordinating Across Social Protection and Humanitarian Assistance – Building on Promising Practices. SPACE

36. As per the Start Network in 2017, including: 1. Direct funding, including of core costs; 2. More equitable and ‘genuine’ partnerships with less subcontracting; 3. Building of sustainable institutional capacity; 4. More presence and influence in humanitarian coordination mechanisms, and support to existing national mechanisms; 5. Greater visibility and recognition of their role, contribution, and achievements; and 6. Increased influence in policy discussions. Patel and Van Brabant. (2017). The Start Fund, Start Network and Localisation: Current Situation and Future Directions. Global Mentoring Initiative.

37. These statistics include international humanitarian assistance to both national/local governments and national/local NGOs. A common trend is for more direct funding to governments, and more indirect funding – including from Country Based Pooled Funds (CBPF) – to NGOs. CBPFs are the largest source of trackable indirect funding. Inconsistencies in indirect reporting make it difficult to verify whether this drop in indirect funding represents a real drop or a reduction in reporting [source: Development Initiatives (2023)].

38. Development Initiatives (2023a) Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023. Development Initiatives

39. Cabot Venton, C. (2021); CALP (2022); Cabot Venton, C. and Pongracz S. (2021) Framework for Shifting Bilateral Programmes to Local Actors. Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE); Lawson-McDowall, J. and McCormack, R. (2021). The Use of Cash Assistance in the Covid-19 Humanitarian Response: Accelerating Trends and Missed Opportunities. Disasters, 45 (S1), S216–S239; Smith, G. (2021). Grand Bargain SubGroup on Linking Humanitarian Cash and Social Protection: Reflections on Member’s Activities in the Response to COVID-19. A report commissioned through Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC)

40. Development Initiatives (2023)

41. Girling-Morris, F. (2022) Funding to Local Actors: Evidence from the Syrian refugee response in Türkiye. Development Initiatives/ Refugee Council of Turkey

42. Humentum (2023) From Operations to Outcomes: A policy blueprint for locally led development. Humentum.

43. Smart, K (2020)

44. Cabot Venton, C. et al. (2022)

45. Cabot Venton, C. and Pongracz, S. (2021)

46. Also noted in recent consultations on training and capacity building carried out by CALP (2023) Consultation Process with Local Actors to Develop CALP’s Learning and Training Strategy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), West and Central Africa (WCAF) and East and Southern Africa (ESAF) Regions. Consultation Report. CALP

47. Cabot Venton, C. (2021); Lawson-McDowall, J. and McCormack, R. (2021); Smith, G. (2021); Bastagli, F. and Lowe C. (2021). Social Protection Response to Covid-19 and Beyond: Emerging evidence and learning for future crises. Working Paper 614. ODI; Development Initiatives (2022) Overhead Cost Allocation in the Humanitarian Sector: Research Report. Development Initiatives. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2022-11/IASC%20Research%20report_Overhead%20Cost%20Allocation%20 in%20the%20Humanitarian%20Sector.pdf; Development Initiatives (2023b) Donor Approaches to Overheads for Local and National Partners. Discussion Paper. Development Initiatives.https://www.devinit.org/documents/1276/Donor_approaches_to_overheads_ discussion_paper.pdf

48.

IASC. (2022). IASC Guidance on the Provision of Overheads to Local and National Partners. IASC.

https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/humanitarian-financing/iasc-guidance-provision-overheads-local-and-national-partners.

50. For example, studies have noted that cash coordination discussions are dominated by bilateral and multilateral donors and UN agencies, working with a limited number of central government representatives. G. Smith. (2021). Overcoming Barriers to Coordinating Across Social Protection and Humanitarian Assistance – Building on Promising Practices. SPACE

51. Kreidler, C., and Taylor, G. (2022)

52. A donor survey in MENA had capacity to manage large-scale responses as the most cited ‘con’ (100% of respondents) to contracting and funding local actors. Technical knowledge gaps (89%) and accountability and transparency processes (89%) were also highly ranked. [NB. This was a small sample of only 9 donors, but likely illustrative of perceptions]. Source: CALP MENA Locally-Led Response (LLR) Community of Practice (2023). Key findings from donors and consortia’s responses on LLR, pros, cons, and perceptions. CALP/ NORCAP

53. Harvey, P. (2022) Floods in Pakistan: Rethinking the humanitarian role, Floods in Pakistan: Rethinking the humanitarian role | Humanitarian Outcomes.

54. GTS (2022) Affected People are Mostly Missing from the Localisation Debate. Let’s Change That. The New Humanitarian. Aid and Policy Opinion, 19th April 2022.

55. The Grand Bargain 2022 progress report includes more extensive summaries of relevant initiatives from signatories

56. IFRC (2021) Strengthening Locally Led Humanitarian Action through Cash preparedness. IFRC; IFRC (2021) Dignity in Action: Key Data and Learning on Cash and Voucher Assistance from Across the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement. IFRC

57. Group Cash Transfer definition: An approach to provide resources in the form of cash for selected groups to implement projects that benefit either a sub-section of the community, or the community at large. Group Cash Transfer is a type of response that seeks to transfer power to crisis-affected populations (typically delimited by geographical location) or community groups to respond to their own needs and priorities.

58. Collaborative Cash Delivery Network (CCD). CCD Presentation to CALP (PowerPoint) – March 2023

60. Development Initiatives (2023a)

62. Based on Cabot Venton, C. and Pongracz, S. (2021); Sharetrust (2022) Local Coalition Accelerator. Sharetrust; and KIIs with IFRC, BRC, Sharetrust, Maan Center for Development, Palestinian Network of Local Organisations and CAPAID Uganda