The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Chapter 1: People-centred CVA

Summary

Key findings

- There is a growing commitment to putting people at the centre of CVA.

- Challenges remain with communication, participation, and feedback.

- Increased attention is being given to inclusion, with more focus on people with disabilities; gender, particularly the needs of women; and displaced populations and people on the move.

- Organizational capacities; mindsets; donor policies; and digital technology are both enablers and challenges to progress on people-centred CVA.

- Better assessment, measurement, and monitoring of people-centred CVA is needed.

- Perspectives differ on how large-scale CVA impacts on people-centred CVA.

Strategic debates

- What needs to be done to make greater progress towards people-centred CVA?

- What are the best ways to reach and serve the ‘most vulnerable’, who are a heterogenous group with different needs and interests?

Priority actions

- Donors and implementing organizations should increase investment in well-designed, independently-led consultation and feedback studies to understand how CVA is working from the perspective of recipients. Such investments would amplify CVA recipients’ voices and contribute to redefining power dynamics between aid providers and recipients. Humanitarian actors should be held accountable to act on findings.

- Humanitarian actors should agree on structures and processes for ensuring accountability to people affected by crises in CVA.

- CVA actors should agree on structures and the process for ensuring accountability to people affected by crisis.

- Implementing agencies should put people at the centre of the digital transformation of CVA. They should make best use of digital technology, maximizing potential benefits while minimizing risks.

- All actors should continue to invest in needs assessments, response and other analyses underpinning CVA, disaggregated data and analysis by gender, age, and disability.

A growing commitment to put people at the centre of CVA is emerging

In key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs), people agreed that there is a growing commitment to people-centred programming, accountability and inclusion which is visible in organizational policies 1. Mainstreaming this commitment across all types of assistance remains an aspiration and so these policies are not usually CVA specific, but some organizations2 have made explicit links or highlighted the issue in their cash-specific policies and guidance.

People-centred programming and CVA in the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement:

“Ensuring participation, communication, and feedback with and from communities in all we do is not optional—it directly informs our CVA work. The Community Engagement and Accountability (CEA) tools we have developed link to our Cash in Emergencies Toolkit – there is a specific module on this, helping national societies to understand the links, and how CVA can contribute to strengthen accountability to communities”. IFRC

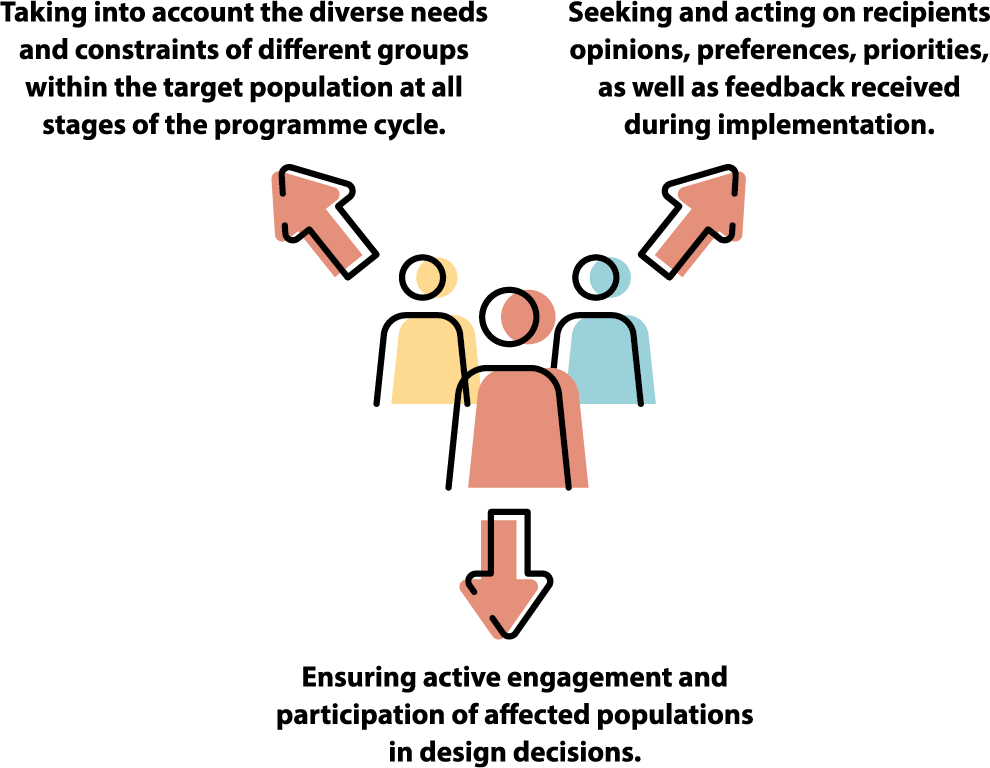

There is a widely felt, genuine desire to do things better. There is no agreed definition of what ‘people-centred’ programming means in the humanitarian sector, key informants and agency policy documents coalesce on key features.

- Ensuring active engagement and participation of affected populations in design decisions.

- Seeking and acting on recipients’ opinions, preferences, priorities, and feedback.

- Taking account of the diverse needs and constraints of different groups within the target population at all stages of the programme cycle.

WFP’s latest cash policy (2023) has three guiding principles, the first is:

“People are at the centre. People receiving money should feel respected and empowered through all their interactions with WFP and its partners. To ensure this, WFP will listen to people’s needs, experiences and aspirations and place them at the centred of its cash operations and its support for government cash programmes.” (ibid:4) 3

Many key informants highlighted that cash (in contrast to vouchers) is naturally conducive to supporting a people-centred inclusive response, providing recipients with greater flexibility and choice than other forms of aid. However, how organizations design and implement CVA programmes determines the extent to which that is realized. Key informants for this report, as in other recent studies4, highlighted that practice is still falling short. Chapter 8 includes debates about the CVA design tensions between technical priorities and people’s preferences. Several of the issues in this chapter reflect issues that are broader than CVA but the fact that they are surfacing in the context of CVA (where cash can be inherently ‘people-centred’) highlights the importance and depth of the issue. Achieving a people-centred response cannot be assumed, it requires active consideration and the right investments.

Challenges remain with communication, participation, and feedback

There was consensus across KIIs and FGDs that some areas of accountability to affected populations have strengthened, but in general, there are weaknesses in practice which constrain meaningful change. 34% of survey respondents identified difficulties in ensuring accountability to affected people as a risk associated with CVA and 19% identified limited investment in accountability as a challenge to ensuring quality CVA. Similar conclusions are reached in other recent research and reports5. The views of key informants on progress and challenges for communication, participation, and feedback on CVA programmes resonate strongly with the findings of Ground Truth Solutions’ (GTS) studies on this topic since 2020. Several people praised GTS for highlighting aspects of CVA design where humanitarian actors routinely fail to put people at the centre and for setting out what practitioners should aspire to in terms of good practices (Box 1.1 summarises key findings).

Communication with communities

Key informants felt that while communication of high-level programme parameters (what assistance people will receive and how they can access it) is generally working well, there are critical gaps in the information agencies routinely share – again, aligned to findings from GTS research.

“We’re better at communicating the easy straightforward messages but weak on communication when there is a problem. But this is where communication is even more important. For example, in the cash response in Ukraine there were widespread delays to payments, this was one of the main issues being reported by Ukrainians through public forums. This should have been a focus of the CWG, to engage on this issue with its members and promote active communication with beneficiaries about the delays. But this was not thought of as a response wide ‘priority’ action that required the CWG’s input.”

This includes information on who will receive CVA (targeting criteria) and for how long. As seen from GTS research (Box 1.1), these information gaps are critical for communities, left unfulfilled they risk undermining programme quality. Lack of proactive communication with communities for troubleshooting problems is another weakness that was raised. All these, arguably basic, issues are indicative of the breadth of change still needed to achieve a truly people-centred approach.

“It’s more than just using close-ended multiple-choice questions to get only the feedback that fits neatly into our pre-existing ideas about programme design. More time needs to be devoted to genuine long-term involvement.”

Participation

A key conclusion in the last State of the World’s Cash report was that humanitarian actors were not doing enough to listen to communities and involve them in programme design. Some key informants perceived that, since then, there has been progress in terms of agencies consulting communities on aspects of design – such as modality preferences. Others, particularly those not affiliated with an operational agency, remained critical. They argued that when participation does take place it is narrowly defined and limited, and therefore neither meaningful nor contributing to change.

Key informants felt that, in general, communities are still not consulted on their priorities, nor on defining other aspects of CVA programme design such as choice of delivery mechanisms (though, as seen in the data and digitalization chapter, there are ways to change this). Several criticized that consultation is still generally a one-way flow of information with no transparency – communities provide information but there is not reciprocal sharing from agencies about why certain information was, or was not, considered in the eventual design. According to one key informant, this form of consultation risks “setting people up to be eternally disappointed”.

Pursuing the issue of modality choice as an example, key informants drew attention to the continued widespread use of vouchers, despite growing evidence that aid recipients are not satisfied with this as a modality (Box 1.1). They commented that the ways that communities were consulted on preferences (generally through close-ended survey questions), and the interpretation of their responses limited the value of the exercise, with a perception that consultations were sometimes used to justify ‘more of the same’. GTS research highlights the need for more critical interpretation of such data. One key informant drew attention to a recent trend they had seen where affected populations had changed their modality preferences from cash back to in-kind, in response to severe food price inflation and related desire for more predictable coverage of needs (see Chapter 5 on Cash preparedness and capacity for more on inflation). All this highlights the need for regular interaction with communities, a better appreciation of what informs preferences and both a willingness and ability to adjust plans.

Feedback

Key informants generally agreed that there has been progress in terms of feedback, with CVA programmes commonly including some form of complaints and feedback mechanism – particularly through hotlines – as well as post-distribution monitoring surveys. This matches views in the literature6. However, many feel there is a lack of responsiveness in terms of feedback informing programming changes. This was also seen in our survey where 26% of respondents highlighted the failure to integrate recipient feedback into programme design and implementation, making it the fourth most frequently cited constraint to quality CVA. As GTS (and other studies) have highlighted, these risk damaging credibility of accountability mechanisms and undermines trust.

“Listening is not enough. We’re listening but what is it changing? What are we doing?”

Key informant“Call centres are creating an illusion, a comfort. They are obscuring a focus on the fact that there is still a lack of meaningful accountability.”

Independent consultant

Box. 1.1. Listening to CVA Recipients: Key Findings from GTS Research 2020–2023

Since 2019, GTS has collected in-depth data on the perceptions and experiences of CVA recipients. This includes the Cash Barometer longitudinal studies in Nigeria, Somalia and Central African Republic, targeted research on modality preferences in Somalia and Nigeria, studies on User Journeys, and multi-country analysis of the perceptions of aid recipients in 10 crises7.

Generally, cash programmes are performing better than other assistance modalities, with perception and satisfaction metrics notably more positive for cash recipients than for others. However, the studies also highlight major gaps that need to be addressed to ensure more people-centred CVA:

- People generally feel aid providers respect them, but very few feel that their opinions are considered.

- Communication and participation are key to recipients’ understanding of quality assistance – people want to be consulted and where processes are strong, satisfaction is enhanced.

- When people do not know the duration of assistance they are unable to plan, undermining recovery.

- Lack of understanding of who is eligible and why undermines people’s satisfaction with programmes and contributes to community tensions. People often perceive targeting to be totally arbitrary (informed by aid providers’ notions of vulnerability rather than communities).

- Feedback mechanisms are often avoided, not just because they are unclear, but because there is little trust that providing feedback will contribute to change.

- People express overwhelming dissatisfaction with vouchers.

- Responses to questions about modality preferences must be treated with caution as various factors can influence this – including limited exposure to alternatives (difficulty of comparing hypothetical alternatives), courtesy bias and inherent power relations between aid provider and recipient (fear of losing assistance).

- Sometimes poor experiences of delivery informs people’s modality preferences, rather than the modality itself e.g. much of the dissatisfaction with vouchers relates to perceptions of poor treatment and vendors’ abuse of power.

- People having changing needs, which is a main reason driving preferences for cash.

- In protracted settings and complex emergencies, people would prefer to see cash better linked with other services and support, and for programmes to focus beyond basic needs, to help support better self-reliance and resilience.

Source: Compiled from a series of GTS publications8

There is growing attention and learning on how to enhance inclusion in CVA

There have been advances in understanding, thinking and practice on inclusion in CVA since the last State of the World’s Cash report. There is greater acknowledgement of the different, and specific, needs and constraints of particular population groups and the need for tailored and sensitive measures to enhance their inclusion. This includes the needs of people living with disabilities, older persons, people of different genders (particularly women), and people on the move.

Inclusion of people with disabilities

Key informants noted the increasing focus and commitment on disability inclusion in CVA since the last State of the World’s Cash report, driven by global policy changes which have created impetus for change9. At the same time, efforts remain in the early stages; specialist NGOs working in inclusion and other key informants highlighted that commitments still need to translate into actions and that several key barriers remain for disability inclusive CVA:

- Lack of empowerment, or meaningful inclusion. People living with disabilities represent some 15% of the population globally. While their inclusion in CVA programming is improving in terms of targeting/coverage, this is not leading to changes in programme design to accommodate their specific needs. Key informants reflected that assumptions are often made about people’s lack of ability rather than consideration of their abilities and agency, with the focus often on finding ways to circumvent the disability rather than address it in design. For example, programmes often simply channel CVA through an intermediary rather than finding ways to actively include people with disabilities. This often renders them dependent on others to access support and contributes to stereotypical narratives and discrimination.

- Lack of diversification of approaches. The needs and constraints to accessing assistance vary, but the importance of diversified approaches is generally not acknowledged or addressed in CVA.

- Gaps in transfer design. There is evidence that people with disabilities routinely face greater costs to meeting their basic needs due to their health issues (e.g. costs of diet, transportation, hygiene products, assistive devices, and medication)10. However, there is little effort to meaningfully accommodate these into the transfer design. These costs are not acknowledged or factored into calculations of minimum expenditure baskets or transfer values11.

- Gaps in accountability mechanisms. There is little effort to ensure that communication mechanisms are accessible to people with differing needs, or to ensure the active participation of people with disabilities to understand their preferences and choices.

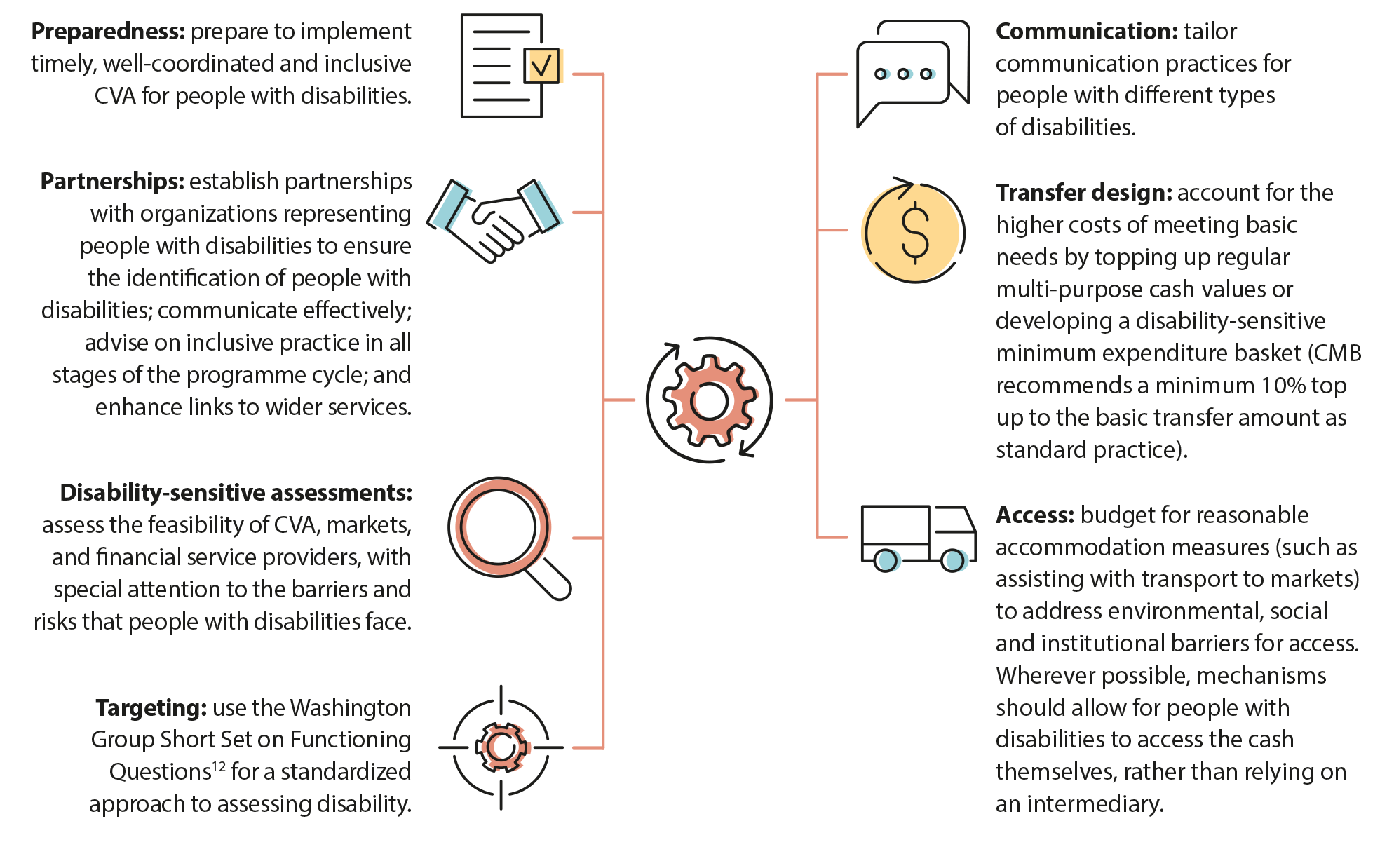

In 2021, CBM Global published a synthesis of learning on good practices, which identifies a range of practical entry points for enhancing disability inclusion in CVA (Graph 1.1). These include some quick wins that could be easily factored into CVA design to make rapid progress.

Graph 1.1: Lessons learned on good practices for disability inclusion in CVA

Source: CBM Global. (2021). Disability Inclusive Cash Assistance: Learnings from Practice in Humanitarian Response.

Gender inclusion, with particular focus on the needs of women

Several key informants noted that there is a growing realization for CVA programmes to be sensitive to and address the needs of people with different gender identities. There is also now greater prominence on gender in the policies of several donors12. Within this, there has been particular focus on enhancing the inclusion of women.

Specialists working on gender and inclusion commented that gendered needs are now being considered more, and there is a growing evidence base on ways that gender-sensitive CVA designs, that support enhanced inclusion of women, can be achieved13. This progress builds on the surge in the production of evidence and guidance on CVA, gender and gender-based violence documented in the last State of the World’s Cash report. However, key informants perceived that increased visibility is not widely translating to changes in practices regarding programme design14.

Key informants highlighted certain organizations, such as WRC and CARE, as good examples of where gender mainstreaming in CVA, which enhances inclusion for women, have been well institutionalized. These organizations have enhanced visibility on gender mainstreaming and gender-sensitive approaches for CVA actors more widely15. Since 2020, there has been interest among several organizations to explore how CVA programmes can be entry points to enhance women’s digital financial inclusion16. There is also increased awareness among CVA actors that while cash can increase women’s agency, alone it is unlikely to contribute to transformation or empowerment. In general, the focus of efforts in this area is seen to have been on gender sensitive, rather than gender transformative, CVA.

Key informants noted progress on issues of safeguarding and gender-based violence (GBV) risk mitigation. Some cash actors have begun to use CVA in comprehensive case management for GBV survivors, while efforts have been made by others to refer people who self-identify as GBV survivors for multipurpose cash transfers. Key informants pointed to the increased availability of good practice tools and guidance on GBV risk mitigation in CVA programmes and on how to use CVA in GBV response17 and calls to action to use cash in GBV response and prevention18. A body of evidence and lessons learned on CVA in GBV response has also been growing recently, which can inform wider uptake going forward19 However, gender specialists reflected that there is still a need to build cash actors’ competencies on GBV risk mitigation and use of CVA in GBV risk management, through engagement of GBV and protections specialists.

Inclusion of displaced populations and people on the move

Since 2020, learning from global displacement crises, including the migration crisis in South America and as a result of the war in Ukraine, has highlighted the potential of CVA as a key tool to support the needs of people on the move in a dignified and discreet way. They also shed light on the need for CVA programme design, where possible, to acknowledge and embrace the realities of human mobility, for people-centred programming20. This differs from work that has traditionally focused on supporting people at their destinations.

Learning includes:

- In contexts where onward mobility is a reality, CVA programmes should factor this into programme registration, verification and monitoring processes, supporting safe movement rather than demanding that recipients stay in one location.

- Engaging with private sector service providers, central banks and governments can help to find solutions to the ID and know your customer (KYC) constraints facing migrants or refugees.

- Accommodating multiple nationalities should be factored into the design of outreach, communication and sensitization materials and CVA processes.

- CVA programme design should stay abreast of data on trends in movement and migration, with responsive designs that support evolving needs (whether transit, or settlement). Those who are settling may need longer term support, and linkages with livelihoods support or social protection.

- Programmes should include support to vulnerable people in the host community where needed.

“One of the biggest innovations is that the financial service providers have made different products [for different groups of people on the move] which we never thought they would before.” Participant in the FGD Americas

Key informants raised political and regulatory barriers as an impediment to more inclusive programming for refugees and people on the move, as well as in conflict settings. Mobility is a politically sensitive topic, and host governments’ and donors’ political motivations, laws and policies influence how assistance is provided. Regulations governing KYC requirements for financial services can also present barriers to inclusion in CVA for people on the move and other marginalized groups. Meanwhile in conflict settings there can be greater political interference with humanitarian CVA, which may present risks to the inclusion of some vulnerable groups, such as seen in Syria where the government is requesting to view and approve all distribution lists. In such settings sensitive approaches to data management are important parts of a people-centred approach (see also Chapter 7 on Data and digitalization).

“For CVA to be people-centred needs and risk assessments need to be inclusive, meaning they need to consider the specific needs and rights of different at risk groups such as persons with disabilities or older people and involve their representative organizations in the process.”

CBM Global

“MPC is not a constraining factor to putting people at the centre. But it is not mechanically an enabling factor, it depends on how the MPC programme is designed.”

UNHCR

“We are seeing inclusion done well in the periphery of CVA programming (such as in cash for protection/and GBV). Not in the main pillars.”

Key informant

There was consensus among key informants that, generally, CVA responses are not adapting to or including the needs, capacities, constraints or preferences of vulnerable groups into their design. Cash assistance from specialist organizations specifically targeting these groups was acknowledged to be tailored to needs, but most people commented that the continued ‘one size fits all’ approach to the design of most programmes (i.e. transfer design and delivery systems) limits inclusion.

Enablers and constraints for more people-centred CVA

Key informants and focus group discussions agreed on several factors that are perceived to influence a move to more people-centred CVA. Some of these reflect systemic issues in aid and are bigger than CVA. However, cash programming (with the opportunities for choice and agency that it offers) highlights these wider dilemmas.

Organizational capacities, and mindsets

Various key informants commented that a key enabler of people-centred programming is when cash actors have the expertise to understand and act on differentiated needs and constraints. They highlighted that transforming practices requires more firmly embedding expertise in day-to-day work, instead of ad hoc training and guidance21.

“Yes, we’re seeing some changes in terms of organizations recruiting specialist positions such as Gender, Disability and Inclusion advisors to address practice gaps in these areas. However, we believe that such positions can make a real difference if they are backed up by addressing inclusion and accountability at the organizational policy and culture level” CBM Global

Numerous organizations have made investments in technical expertise in recent years, recruiting inclusion and accountability specialists to support mainstreaming across CVA (and other) programmes, as well as investing in partnerships with specialist organizations and related training and guidance. Different agencies are at different stages of internalizing these ways of working in CVA. Embedding in-house technical expertise can be beneficial, but key informants highlighted the need for all organizations — national and international — to understand the fundamentals of people-centred CVA and called for more efforts to make expertise publicly available (perhaps through guidance, capacity exchanges, etc.) so all organizations can make these shifts.

“We are still organization-centric, not people-centric.”

Ground Truth Solution

“The mainstream humanitarian agencies need to let go of power for us to see real change. In relation to needs assessment that means recognizing how their vested interests shape their understanding of a problem they are trying to solve.” ACAPS

Key informants perceived that investments must go beyond technical know-how and that a change in organizational structures, processes and culture was also needed to effectively put people at the centre of programming. Practitioners recognize that the latter can be difficult as it requires a shift in perspective within implementing agencies – putting what people value, rather than what an organization deems to be important, at the centre of programming decisions and business processes. The fact that there is some acknowledgement of this is a positive step, but key informants outside of implementing organizations were pessimistic about the likelihood of achieving these fundamental shifts in practice. They also referred to the paternalistic approach to aid design entrenched in providers’ mindsets and noted that self-interest motivates – in part – an organization’s design decisions.

Donor policies

Donor policies are acknowledged to be orienting in favour of more people-centred responses but key informants were not yet seeing commitments following through to systemic changes in the way donors fund CVA. They highlighted several ways in which donor funding can be a barrier to progress on people-centred CVA:

- Over focus on cost efficiency – key informants highlighted that while a focus on cost efficiency is important, especially in the context of increasing humanitarian needs and limited resources, too much focus on these metrics has trade-offs in other areas and can undermine people centred, quality programming. For example, a CVA programme introduced two delivery mechanisms that enhanced recipients’ satisfaction with the programme because it responded to and addressed issues in accessibility, but the donor criticised it as an inefficient and costly duplication. Key informants argued that to advance the agenda on people-centred CVA requires donors to better reflect on effectiveness and equity considerations as well as costs.

“The focus is more on the cost efficiency than the value for people. There is always 20% of people who struggle.”

Key informant

“If we [implementers] are under pressure to do CVA really quick or at scale and donor requirements are pointing to this in their performance targets, it’s inevitable that principles like inclusion will fall off and quality and accountable programming will be affected”. CBM Global

- Limited reflection of AAP/inclusion in funding decisions – key informants highlighted that the right incentives for change are set when donors have internalized commitments to inclusion into their funding decisions, such as through requirements for partners to present a gender analysis. In contrast, when accountability to affected populations and inclusion aspects are not required, or scored, in funding decisions (which people reflected is generally the case still), this doesn’t incentivize change.

- Inflexible funding instruments – a range of key informants, including donors, commented on the lack of flexible funding instruments. Issues raised include: the continued earmarking of assistance; processes that require implementing partners to define elements of proposed programme design before they’re able to consult populations; risks of designing people-centred CVA only for it to not be funded – undermining hard-won relationship building efforts with communities; and a lack of flexibility for adapting design (e.g. between modalities) as the context changes. In our survey, 29% of respondents highlighted the inability of funding mechanisms to respond to such changes, making it the third most cited barrier to quality CVA.

Digital technology

The increasing use of digital solutions in the CVA delivery chain was highlighted both as a potential enabler and as a constraint for more people-centred and inclusive programming. Key informants were positive about the possible transformative potential of these technologies on CVA programmes. This includes, for example, innovations supporting safe, and remote, registration and delivering payments to people on the move and in hard to reach areas; enhancing access to payments for those with mobility restrictions or without IDs; providing innovative mechanisms for enhancing communication and feedback; providing an entry point for diversifying CVA design (e.g. transfer value) according to need; and the potential for digital platforms to link CVA recipients to wider services (see Chapter 7 on Data and Digitalization). However, digital solutions also present risks to inclusive and accountable programming that, as key informants highlighted, need to be better acknowledged and addressed (Box 1.2). This includes, for example, inclusion barriers due to digital literacy or KYC and the risk of reducing community engagement – and thus accountability from use of technology.

Recent studies on digital inclusion in CVA highlight similar pros and cons, as well as the need for greater appreciation of the concept of ‘digital dignity’ and active engagement of CVA recipients in decisions on the use of their personal data22. Key informants also stressed the importance of engaging and consulting target populations to ensure that digital solutions are in line with their own preferences and any constraints or concerns are mitigated.

Box 1.2. Factors influencing accountability and inclusion on CVA in the Ukraine response

For displaced populations and those in hard-to-reach areas of Ukraine, digital solutions played an important role at multiple stages of the CVA delivery chain – from the use of remote online self-registration portals to digital payment solutions using mobile technology, and remote monitoring. This enabled access to assistance, at scale, in a context with robust digital infrastructure and a generally digital literate population. However technological solutions were followed without sufficient understanding of or efforts to address access barriers for those who are less familiar with digital technology (people with disability and older people) and people in rural areas who lacked access to smart phones and internet. This led to exclusion of the very vulnerable. It had been assumed that others in the community would assist these people but no specific actions were taken to facilitate this and registration data found few instances of registrations on behalf of a third party.

National chapters of specialist organizations with links to vulnerable and excluded populations, such as HAI and CBM Global, contributed to improving inclusion challenges – such as outreach and sensitization, as well as face-to-face registration exercises to overcome access issues. They also assisted households in navigating the bureaucracy of registration and the documents required. This showed that outreach and efforts to accompany CVA recipients through administrative processes can help to close inclusion gaps, when planned and budgeted for as a purposeful action and through strategic partnerships with specialist organizations (which could include national and local organizations).

Key informants also highlighted that the digital self-registration processes were a source of inefficiencies, as they left space for duplication. They argued that it would not necessarily have cost more to enhance inclusion, as reducing programme leakages could free up resources to enhance access for those who were excluded.

Finally, in the cash working group (CWG) there was a strong push to have a unified approach to setting the transfer values for basic needs assistance. While there were benefits to a coordinated approach across organizations and territories, it also reduced agencies’ agility to adjust to the needs of specific groups. To influence these transfer values, CBM Global published evidence that people with disabilities have an income gap due to their increases needs for assistive devices, care needs and medication.

Source: Based on various published reports23as well as KIIs.

Assessment, measurement and monitoring

“We need to go beyond measuring numbers. We are not asking the right questions”

World Vision International

“One of the biggest problems is that there is no requirement to report on this (inclusion)”

Key informant

Various key informants commented on the need for better measurement of results. Attempts to measure quality of CVA have been limited and overarching issues need to be addressed. For example:

- There remain gaps in data disaggregation that are a starting point for better monitoring of inclusion.

- Effectiveness of consultation and feedback processes is rarely monitored. Measures of success (outcomes) remain, for the most part, agency-defined.

- The inclusion of people-centred indicators is mainly limited to asking closed questions about satisfaction with assistance.

Key informants criticized these narrow metrics and highlighted that more granular (including qualitative) information was needed to draw accurate conclusions to inform design. Again, they highlighted the need to consider how power relations can influence responses.

Relatedly, key informants working in accountability and inclusion noted that arguments against investing further in accountability or inclusion measures often point to the higher costs of such measures. However, they felt such arguments are often based on assumptions which could be inherently flawed. They further argued that we need to avoid assuming that doing things better will necessarily cost more, and instead consider how looking at this ‘low hanging fruit’, and through good end-to-end programming that avoids or reduces inefficiencies in other areas, costs can be absorbed. Examples in Ukraine (Box 1.2) were cited to support this. Key informants argued that even if there are additional costs, CVA programmes that are more people-centred from the outset and that more effectively reach and serve the most vulnerable, present a more cost-effective use of resources. They argued that there is a need to capture the results of people-centred design, showing both the benefits as well as costs.

Some key informants also highlighted that there is no accountability for people-centred CVA. Generally, agencies are not required to and do not report on people-centred outcomes as part of performance monitoring24. Even if monitoring does improve, it may not lead to changes unless there are incentives in place to act on the data25.

Programme scale and people-centred CVA

KIIs and FGD participants shared diverse perspectives on how CVA programme scale can influence a people-centred response. These differing perspectives highlight that the relationship between scale and inclusion needs to be considered in terms of: (i) access to aid, and (ii) the ability for that CVA to adequately meet the needs, constraints and preferences of different groups of people.

“We focus on the majority. Scale encourages a focus on reducing individual and HH-level needs to fit into just a few boxes.”

FGD participant

“Scale makes it more difficult to tailor assistance to all groups, a bigger programme tends to be more standardised. However, big programmes also have more resources and should be able to work on this.”

SDC (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation)

“Look at delivery mechanisms – if there is no alternative delivery mechanism offered on a programme, this is not an issue of scale, it is an issue of design. Scale should not be an excuse for a lack of quality.”

NGO

On the first dimension, greater scale can equate to greater coverage of those in need and thus inclusion in terms of access to aid. Agencies leading cash responses at scale in contexts of widespread vulnerability and insufficient or dwindling funds face a dilemma in the trade-off between coverage and transfer adequacy. Often affected populations will express a desire for more people to be assisted – whereas humanitarian actors aim to focus on the ‘most vulnerable’. Agencies can include more people, but then are constrained in their ability to design a response that is sufficient to meet needs. This presents a barrier to achieving more people-centred CVA.

On the second dimension, key informants highlighted that large scale cash programming often still equates to a one-size-fits-all design. This trade-off between CVA scale and ability to meet differentiated needs and preferences was widely noted, with multiple people commenting on the 80:20 effect wherein the most vulnerable risked exclusion from large scale assistance. Some of this was seen as being a constraint inherent in scale, i.e. that for manageability, it will never be possible to tailor programmes designed to reach millions to meet all individual needs, requests and requirements. On the other hand, many people cautioned about practitioners using scale as an excuse. They considered that with the right planning and willingness, it is possible to introduce more diversification and people-centred elements into the design of CVA at scale (e.g. in transfer values; in delivery mechanisms; in last mile solutions enhancing access for particular groups) and that now greater scale has been achieved, more efforts are needed to improve quality.

Finally, there were people who thought it was important to do more to diversify the design of scalable CVA, but it is possible to have more than one way of working and that scalable responses don’t need to solve all inclusion issues. For the very vulnerable (the 20%), they said that separate tailored interventions could fill these gaps to (perhaps better) meet these needs.

Implications for the future: Areas for strategic debate and priority actions

Areas for strategic debate

Our analysis highlighted the following considerations to inform further thinking and progress in this area.

- What needs be done to make greater progress towards people-centred CVA? To truly move towards people-centred and inclusive programming requires that humanitarian actors establish and monitor appropriate accountability and inclusion targets with measurable performance indicators. Without this, the pressure to meet other performance targets (generally oriented towards efficiency) will continue to constrain progress. Monitoring should include perception indicators from those that CVA aims to serve and capture indicators relating to inclusion (who is part of the programme), participation (how they engage in and shape the programme), and accountability (how they hold to account those responsible for providing the assistance).

- What are the best ways to reach and serve the ‘most vulnerable’ 20%? There are, potentially, multiple pathways through which this can be achieved including: (i) better mainstreaming of an inclusion lens and good practices into the design of CVA for the 80%; (ii) designing and funding specialized CVA programmes that target and address the additional needs of specific groups; and (iii) improving linkages to other services. This also has implications for the roles of specialized organizations with expertise in gender, disability and inclusion, which can be involved as technical partners in large CVA programmes or can assume direct implementation of specialized CVA programmes serving specific groups.

Priority actions

In relation to the strategic debates above and other key findings in this chapter, the following are recommended as priority actions for stakeholders:

- Donors and implementing organizations should increase investment in well designed, independently led, consultation and feedback studies (such as the user journey research of GTS) to generate learning about how well or not CVA is working from the perspective of the people aid aims to serve. Such investment would amplify CVA recipients’ voices in an independent and methodologically sound way and could contribute to redefining power dynamics between aid providers and recipients. To be meaningful, such studies should be independent, combine quantitative and qualitative approaches and ‘ask the right questions’.

- Humanitarian actors should be held accountable to act on information received. Such actions will be most effective if undertaken in conjunction with other recommended actions.

- Structures and processes for ensuring accountability in CVA should be developed within the humanitarian system.

- Implementing agencies should put people at the centre of the digital transformation of CVA. To make best possible use of digital technology and maximize the potential benefits of innovations while minimizing risks, decisions on whether, and how, to integrate digital solutions should include consideration of: (i) affected populations’ preferences; (ii) their familiarity with different options and barriers or risks associated with the use of technology; and (iii) a sufficient investment in measures to overcome these (such as through addressing digital literacy).

- All actors should continue to invest in needs assessments and other analyses underpinning CVA, including response analysis, ensuring analyses are disaggregated by gender, age, and disability. The participation of people with disabilities and their representative groups is key.

1. CALP. (2022). Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP

2. Including RCM; Mercy Corps; UNHCR; IOM; ECHO; WFP

4. Ibid; also echoed in Metcalfe-Hough, V., Fenton, W., Saez, P. and A. Spencer. (2022). The Grand Bargain in 2021: An Independent Review. HPG Commissioned Report. ODI.

5. Ibid; GTS (2022). Affected People are Mostly Missing from the Localisation Debate. Let’s Change That. The New Humanitarian. Aid and Policy Opinion, 19th April 2022. ; Seferis, L. and P. Harvey. (2022). Accountability in Crises: Connecting Evidence from Humanitarian and Social Protection Approaches to Social Assistance. BASIC Research Working Paper 13. Institute of Development Studies.

6. Ibid; V. Barbelet. (2020). Collective Approaches to Communication and Community Engagement in the Central African Republic. Humanitarian Policy Group. Overseas Development Institute.

7. Including Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Chad, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Nigeria, Somalia, Syria, and Ukraine

8. Seilern, M. and H. Miles. (2021). CVA, Plus Information: what Happens when Cash Recipients are Kept in the Loop? Ground Truth Solutions blog post 15th March 2021; H. Miles. (2022). Modality Preferences: Are Uninformed Choices Leading us Down the Wrong Road? Ground Truth Solutions blog post 30th January 2022; GTS. (2022) The Participation Gap Persists in Somalia: The Cash Barometer February 2022. GTS; GTS. (2022). Listening is Not Enough: People Demand Transformational Change in Humanitarian Assistance. Global Analysis Report, November 2022. GTS.

9. IASC Guidelines on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action were launched in late 2019; followed by the UN Disability Inclusion Strategy in 2020. Under the IASC there is now a disability reference group, co-led by UNICEF with CBM Global and Intl Disability Alliance (IDA).

10. CBM Global estimates it as 10—40% higher costs (KII).

11. CBM Global. (2022). Technical Brief: Key Principles and Recommendations for Inclusive Cash and Voucher Assistance in Ukraine. European Disability Forum / CBM Global.

12. Also highlighted in CALP. (2022). Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies. CALP

13. For example, as set out in V. Barca et al. (2021). Inclusive Information Systems for Social Protection: Intentionally Integrating Gender and Disability. Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19: Expert Advice (SPACE); and Holmes, R., Peterman, A., Quarterman, L., Sammon, E. and L. Alfers. (2020). Strengthening Gender Equity and Social Inclusion During the Implementation of Social Protection Responses to COVID-19. Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19: Expert Advice (SPACE)

14. For example, the FGD with STAAR GESI experts highlighted that inclusion can be limited to superficial statement on “inclusion of women and girls”, inserted into programme documents. Similar findings have been highlighted in Metcalfe-Hough et al. (2022); CALP (2022); Maunder, N., McDonnell-Lenoach, V., Plank, G., Moore, N. and L. Begault. (2022). Better Assistance in Crises (BASIC) Performance Evaluation. Midline Report. A report by Integrity Research and Consultancy; and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the World Bank Group. (2022). Digital Cash Transfers in the Time of COVID-19: Opportunities and Considerations for Women’s Inclusion and Empowerment. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the World Bank Group.

15. The Cash Workstream of the Grand Bargain started a sub workstream on gender in cash in 2018, led by CARE and UNWOMEN, which operated into mid-2021. This was considered to have made the topic more visible for cash actors through producing and sharing guidance, tools and case studies and hosted various events and learning opportunities.

16. Including Mercy Corps, WFP, and Oxfam

17. Including from WRC, CARE, and UNFPA.

18. Guglielmi, S., Mitu, K., Jones, N., and M. Ala Uddin. (2022). Gender-based Violence: What is Working in Prevention, Response and Mitigation across Rohingya Refugee Camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh? Gender and Adolescence Global Evidence. ODI.

19. SPIAC-B. (2022). Resource Sheet on Gender-based Violence and Social Protection from the SPIAC-B Gender Working Group. SPIAC-B; CARE. (2020). Gender-Based Violence and Cash and Voucher Assistance: Tools and Guidance. CALP.

20. From FGDs and KIs with stakeholders working in the LAC region and Ukraine, plus recent publications: CALP. (2022). People are on the Move: Can the World of CVA Keep Up? Analysis of the Use of CVA in the Context of Human Mobility in the Americas. CALP; IFRC. (2022). Dignifying, Diverse and Desired: Cash and Vouchers as Humanitarian Assistance for Migrants. IFRC

21. Other recent studies have reported similar findings regarding how lack of capacities limits inclusion in practice. For example, Maunder et al. (2022) which highlighted that the GESI advice given under SPACE led to new thinking by FCDO advisors on how to make emergency programming gender-responsive, but that such short-term technical assistance cannot address wider structural gaps in capacity.

22. Barca et al. (2021)

23. Including CBM Global (2022); T. Byrnes. (2022). Overview of the Unified Information System of the Social Sphere (UISSS) and the eDopomoga System. Social Protection Technical Assistance, Advice and Resources Facility (STAAR). DAI; Tonea, D. and V. Palaciois. (2023). Role of Civil Society Organisations in Ukraine: Emergency Response Inside Ukraine. Thematic Paper. CALP

24. Also highlighted in a 2020 Blog by GTS and CALP on improving AAP in the new HRPs, which criticized the HRP’s focus on monitoring only as far as the inclusion of AAP in the HRP, not actual progress/performance against these plans and targets and not including perceptions of recipients.

25. GTS. (2022). Listening is Not Enough: People Demand Transformational Change in Humanitarian Assistance. Global Analysis. GTS