Cash and Voucher Assistance Policy and Funding

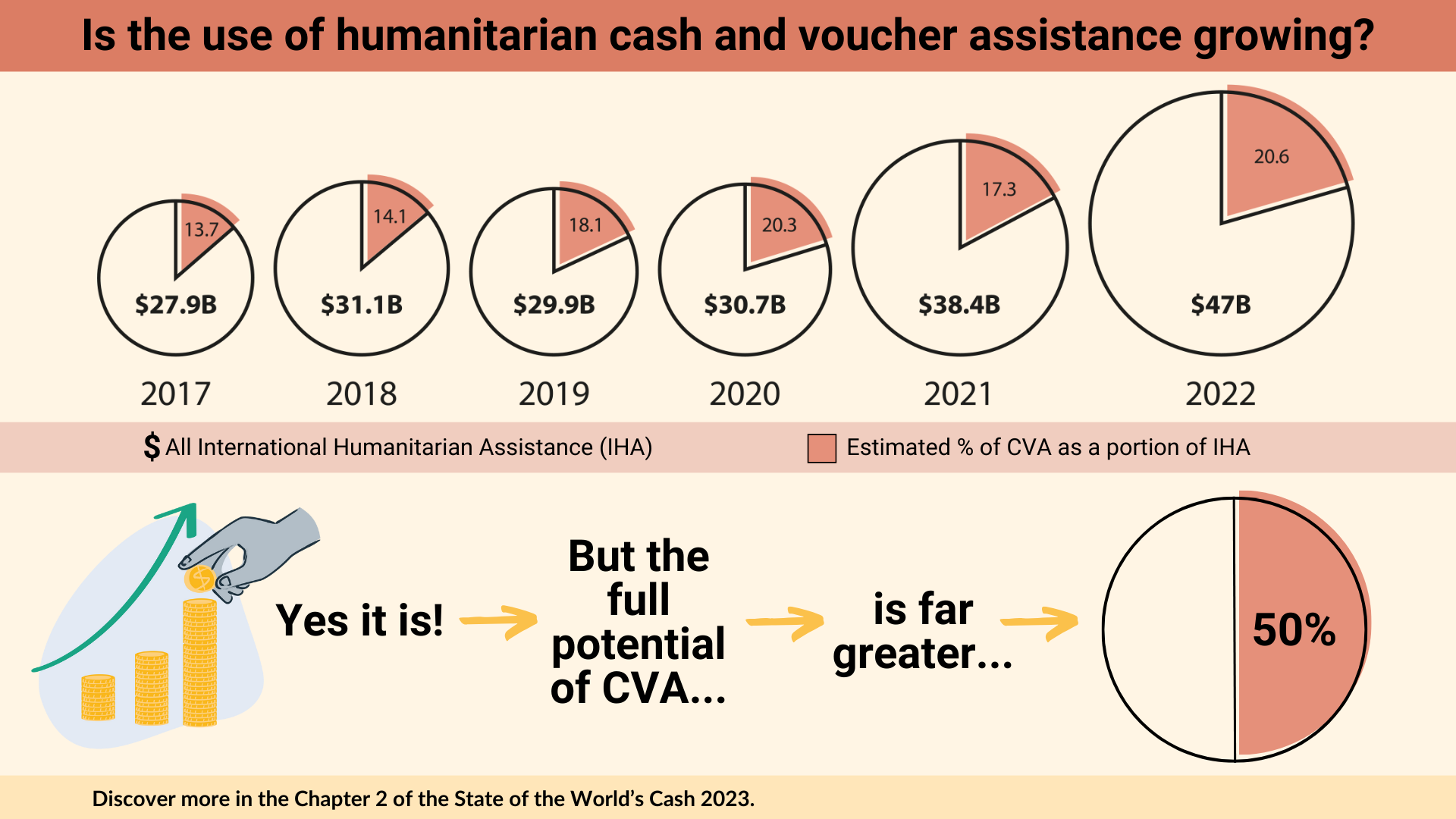

Cash and voucher assistance has grown rapidly in the last few decades, now accounting for approximately 20% of all humanitarian assistance.

This success has been in part due to the commitments made during the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, the Grand Bargain framework where stakeholders committed to the routine use of CVA and many other high level policy commitments.

Sokhna outlines that for cash and voucher assistance to fully meet its potential four major changes are needed.

Is the use of CVA increasing?

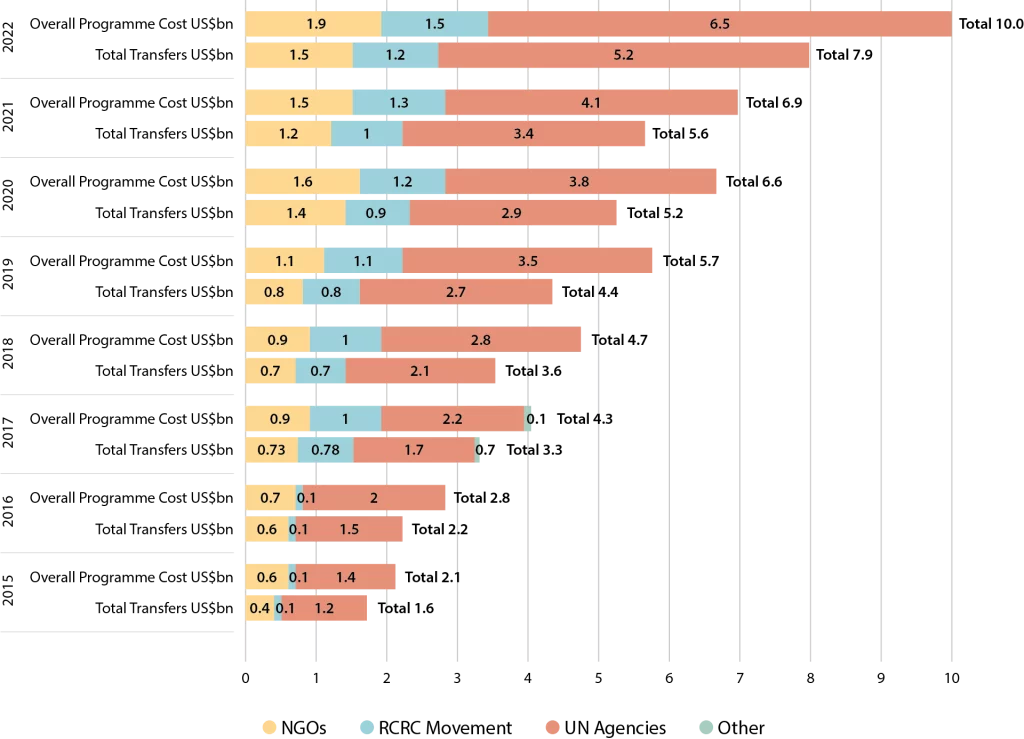

Cash and voucher funding continues to increase year on year, reaching $10 billion in 2022. This was the seventh consecutive year-on-year increase, and 2022 was the largest increase (in spending) on record.

Between 2017 and 2022, the total volume of CVA transferred to recipients more than doubled – growing from US$3.3 billion in 2017 to US$7.9 billion in 2022.

However, looking at data by volume of spending only provides part of the picture. In 2022, CVA comprised just over 20% of international humanitarian assistance, only slightly higher than the 18% in 2021. This is a much smaller increase than in the previous year.

CVA could make up a much greater proportion of aid than it currently is. Research suggests that if CVA was delivered wherever feasible and appropriate, it would make up 30–50% of all international humanitarian assistance.

Transformational change is needed in the humanitarian system to increase the use of CVA. Global, national, and institutional policies are key to making that happen.

What is the volume of cash vs. vouchers?

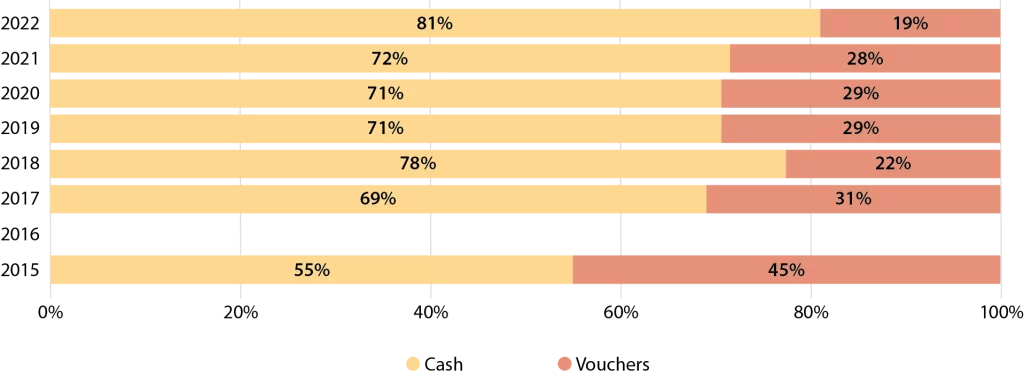

Data from 2015 to 2022 shows that most spending on CVA goes towards providing [cash transfers] directly and a far smaller proportion is spent on vouchers. After staying largely static at 71–72% for three years between 2019 and 2021, the use of cash increased to 81% of CVA in 2022, with vouchers comprising 19% of reported totals. The shift towards cash in 2022 might be partly attributable to the large-scale use of cash assistance in the Ukraine crisis response.

Cash is more widely used partly because of a well-documented recipient preferences for cash (over vouchers or other modalities of assistance) in most cases. Associated with this, going back to at least 2015, there has been policy level push for cash, rather than vouchers.

CVA Funding

How is CVA funded?

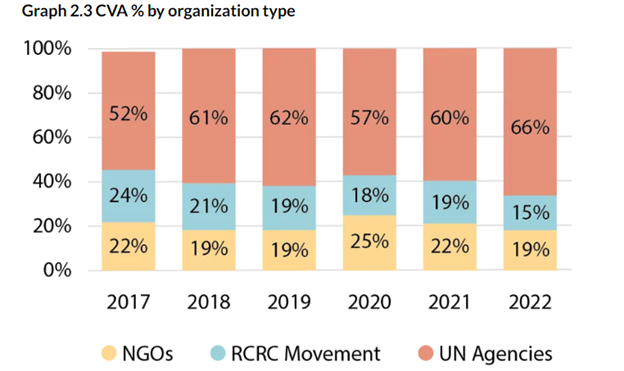

In 2022, the majority of CVA was provided by UN agencies, which accounted for 66% of all spending. NGOs had the second largest spend, followed by the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, then others.

But these figures can hide who is actually delivering the assistance. Often bigger agencies work with partners to deliver humanitarian programmes – including CVA. Any funding which is sub-granted to an implementing partner is not visible in the tracking data – resulting in a lack understanding of how much local actors contribute to the delivery of CVA.

Two of the big funding pools for the humanitarian sector are the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and Country-Based Pooled Funds (CBPFs), managed by the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Research by CALP found that some Country-Based Pooled Funds had targets for the use of cash. It also found that funding allocations via CERF were substantially lower than the global average use of cash in humanitarian response.

A key in-depth resource to understanding CVA volume and growth is chapter 2 of the State of the World’s Cash 2023.

CVA Policy

Donor commitments

Policy commitments to increase the use of humanitarian CVA and active donor support for CVA policies have been a big driver of growth.

Other key donor commitments to CVA are:

- The Donor Cash Forum: A space for donors to discuss and advance shared positions on key themes related to cash transfers. In recent years, they have developed policy guidance on cash coordination, and the use of cash in high inflation and major crises, such as Covid-19.

- The Common Donor Approach to Humanitarian Cash Programming: A commitment signed in 2019 by ten of the largest donor governments pledging support for cash programming.

- The Joint Donor Statement on Cash: An agreement made in 2019 by major donor agencies (EU/DG ECHO, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, UK and USA) which identifies priority areas where donors can improve coordination.

CVA policy commitments

One of the biggest policy commitments for humanitarian action in recent decades is the [Grand Bargain]. This high-level agreement between some donors and humanitarian actors aimed to make aid more efficient and reach more people in need – including increasing the use of CVA.

Aside from the Grand Bargain, there are many other significant multi-agency commitments, such as:

- UN Common Cash Statement: OCHA, UNHCR, WFP and UNICEF’s policy commitment to a common cash delivery system, interoperable data systems and other joint approaches in the cash delivery chain.

- Common Cash Delivery Network: 14 international NGOs committed to collective action towards using CVA at scale, using shared systems, delivery capacity and quality approaches.

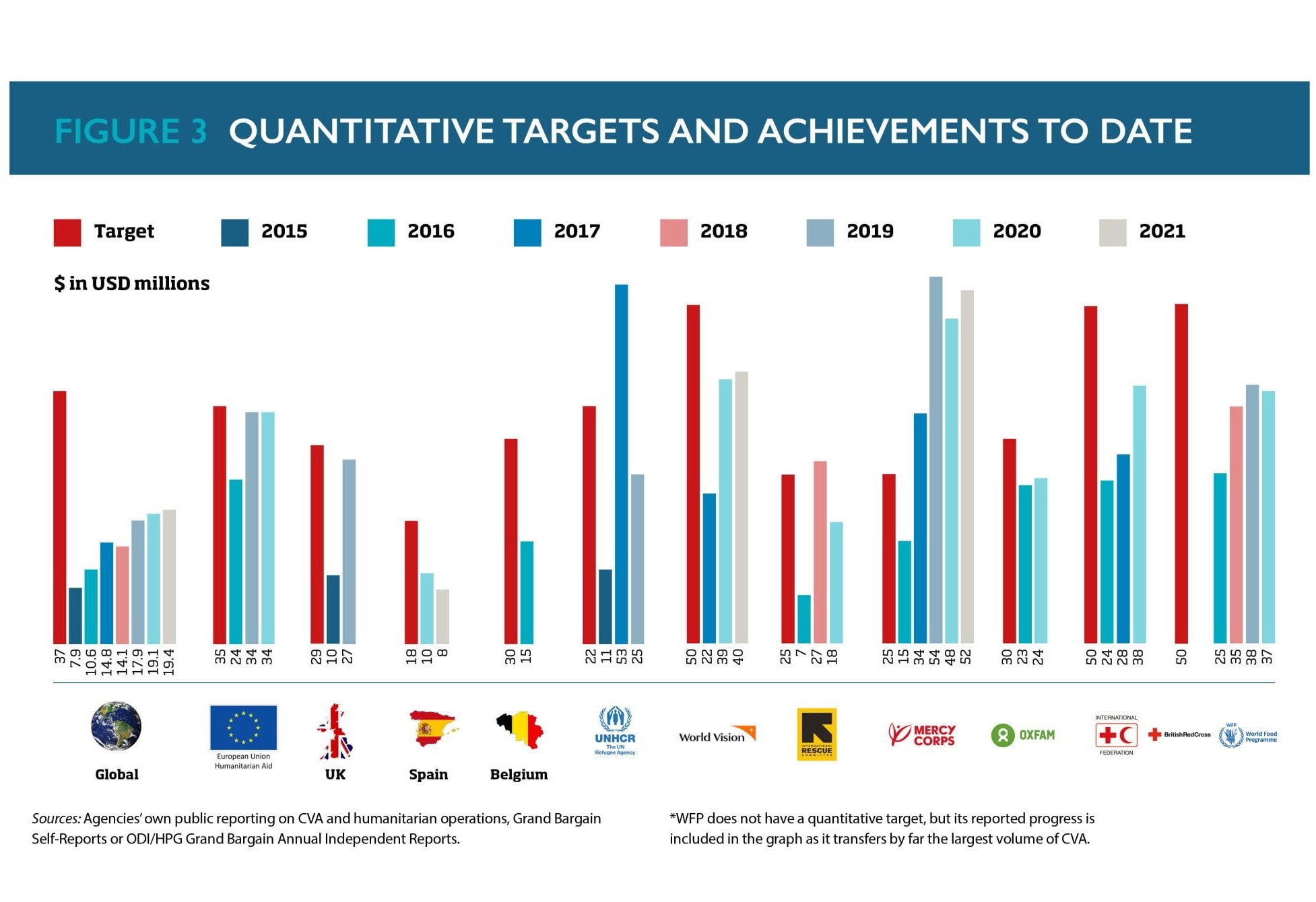

In addition, individual agencies set their own policies to reach certain targets to deliver CVA

The CVA policy environment has evolved hugely since 2016, with enormous progress in many areas. Organisations are influenced by a variety of policy factors when it comes to CVA. Collective commitments have provided a foundation for progress, with external commitments, internal motivation and environmental factors all playing a part in accelerating change.

For a detailed assessment of the CVA policy landscape please refer to Where Next? The Evolving Landscape of Cash and Voucher Policies.

Understanding the Grand Bargain

The Grand Bargain is one of the biggest global commitments by donors and humanitarian organisations in recent years that is designed to make humanitarian action more efficient and reach more people in need.

The Grand Bargain was proposed during the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016 as a solution to bridge the gap between the size of the humanitarian need and the amount of money available for aid. By making aid more direct with fewer administration costs, it was estimated the system could yield an extra billion dollars in savings.

In the lead up to the summit this influential 2015 paper asked the now-well known phrase ‘why not cash?’ and ‘if not now, when?’”. These words set the tone for conversations around CVA.

The Grand Bargain has had a big impact on CVA, and the growth of CVA has been one of the most successful areas of the pact. Since 2016 the use of cash has been widely embraced and its use as a proportion of humanitarian assistance has doubled.

For the Grand Bargain 2.0, efforts shifted to focus on addressing the challenges of accountability and coordination in the delivery of CVA. In 2022, following a call for action, signatories agreed on a cash coordination model to formalise cash into the existing coordination model to formalise cash into the existing coordination model.

To find out more, read our Grand Bargain page on the Cash 101.

Opportunities and challenges involved in scaling up CVA.

What opportunities are there to scale up CVA?

- Switch more assistance from in-kind to CVA where appropriate.

- Organisations should continue to make changes to hit their own targets for the use of CVA.

- Increase the use of multipurpose cash. Coordinate efforts between all actors in multiple places.

- Harmonise approaches to improve the quality of CVA responses. Many issues that need to be addressed are technically feasible but require substantial political will as they impact interagency relationships and funding flows.

- Develop stronger links with development aid and national social protection systems.

What are the barriers to scaling up CVA?

- Donors donating in-kind aid rather than cash to humanitarian actors. For example, in a 2022 study, CALP found that if U.S government funds related to food aid had been redirected towards CVA, this would have led to a 6% boost to total global volumes of CVA (i.e., up from 19.4% to 25.4%)!

- Some humanitarian sectors are hesitant to change from in-kind aid to CVA.

- Decisions on the type of aid are sometimes made based on the volume of existing in-kind stocks, rather than the preferences of people affected by a crisis.

- Risk aversion and lack of willingness of some organisations and crisis-affected governments to enable CVA programmes. Some actors who are not familiar with CVA continue to opt for in-kind assistance.

However, these only serve as examples. The potential growth in the use of CVA will only be realised through multiple actions, by multiple organisations, in multiple places. There is not one simple untapped reservoir to achieve growth nor simple levers to create change.

For deeper analysis read CALP’s 2022 trio of publications on this topic: Where next for CVA: Time to get more radical?

Or you can watch this 16 minute training video about CVA standards and policy environment from 2020.