Cash & Voucher Assistance Design and Delivery

Providing people with Cash and Voucher Assistance (CVA) during disasters and emergencies means that they can decide for themselves how to meet their needs in the face of crises.

Who and what is involved in the planning, design and delivery of CVA? When are cash and/or vouchers appropriate? How are transfer amounts, and recipients identified? This page explains the practical elements around how CVA is designed and delivered.

But before we dive in, Sokhna presents four big picture ideas around improving CVA design and delivery.

What are the steps involved in delivering cash and voucher assistance?

All humanitarian interventions follow a programme cycle. The core steps are the same for all programmes, with the specifics depending on the type of programme. A typical CVA programme cycle involves:

- Preparedness: CVA preparedness is critical in enabling timely and successful responses. It includes building CVA capacities and systems within and across organizations. As part of this, organizations gather information, identify payment options and service providers, build partnerships, and identify targeting options.

- Assessment and analysis: This involves gathering and analysing information to assess the needs and preferences of the population, determine if markets are functioning and accessible, and understand the context and operational feasibility of CVA. It includes an assessment of which payment mechanisms are available and accessible to crisis affected people. All this informs the ‘response analysis’ and the decisions on which types and combinations of assistance to use.

- Design and implementation set-up: This involves detailed planning for multiple activities including registration, targeting, setting transfer values, selection of payment mechanisms, monitoring, accountability mechanisms, etc. It requires working with partners and suppliers, such as financial service providers (FSPs), to establish the operational processes needed. It also involves engaging with other stakeholders such as Cash Working Groups (CWGs) to ensure a coherent, and harmonized response.

- Distribution cycle and monitoring: This consists of the selection and registration of recipients, distribution of cash and/or vouchers, and related administrative, financial, monitoring and accountability processes. Various forms of data are collected throughout this period, including feedback from recipients and changes in market prices. Analysis of the data is then used to inform adjustments made to the programme design.

- Exit: An exit strategy should be developed during programme planning.

To learn more about the programme cycle and market assessments, visit CALP’s Programme Quality Toolbox, complete the free CVA -The Fundamentals course, or take the 30-minute Introduction to Market Analysis course.

When should cash and voucher assistance be used?

Cash and Voucher Assistance (CVA) can be used as part of disaster preparedness, in anticipatory action, as emergency relief or to support recovery from a crisis.

For example, CVA can be used to:

- Enable a farmer in a flood or drought-prone area take steps to reduce flood risks (an example of disaster preparedness).

- Support displaced people to meet immediate basic needs, such as food or cooking fuel, during a conflict (an example of emergency relief).

- Help small businesses replace ruined stock and equipment following a typhoon (an example of recovering from a crisis).

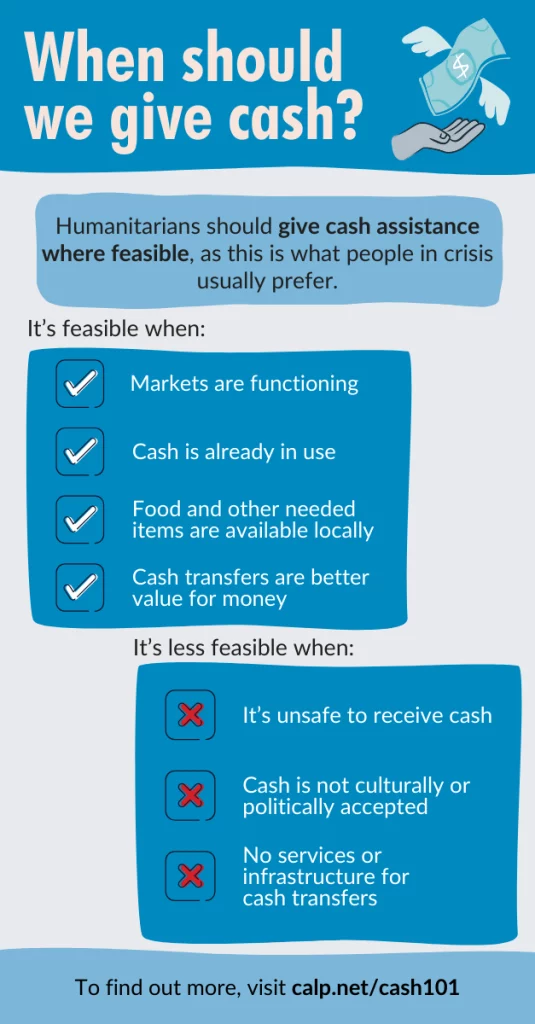

When is CVA appropriate?

There are four main factors to consider when deciding if CVA is appropriate in a given humanitarian context:

- Understanding needs and preferences: In most cases people in crisis prefer cash rather than in-kind assistance, but this is not always the case. In some contexts, people may prefer in-kind assistance, or a combination of both cash and in-kind.

- Market conditions: There needs to be safe, accessible, and functioning markets for goods and services, with sufficient stock and variety to meet demand.

- Operational conditions: There is need to consider whether CVA can be delivered safely, if there are functional and reliable payment systems available, if a reliable recipient identification system can be established, whether CVA offers good value for money, and if the agency has the expertise to deliver CVA well.

- Community and political acceptance of CVA: Stakeholders such as national and local government, local leaders, crisis-affected populations must be supportive of the approach.

The CVA Appropriateness and Feasibility Analysis section of CALP’s Programme Quality Toolbox has a useful resources to assess if CVA is the right type of assistance for a response.

To find out more, visit our what is CVA and types of CVA pages.

CVA as part of disaster preparedness

In areas at risk of disaster, CVA can be used to help people and communities prepare, respond, adapt, and build resilience.

For example, CVA can give people at risk the means to:

- Cover evacuation costs of moving people or animals in anticipation of a flood.

- Stock-up on food in case of emergency.

- Invest in drought-resistant crops.

- Construct dikes, or clear and maintain drainage to prevent the impact of floods.

- Stock in-demand items if they are traders, to support markets and stabilise supply and prices.

Please note that ‘CVA preparedness’ has a different meaning to ‘disaster preparedness’. The former refers to putting measures in place so that CVA can be delivered in a timely, accountable and effective fashion, the latter has a broader meaning around general preparedness in anticipation of a potential disaster

Find out more about CVA and disaster preparedness.

Disaster relief and recovery

CVA is used in both disaster relief and recovery. There are several ways CVA can be used to:

- Provide immediate relief: Cash allows flexibility for affected households to buy what they need following a disaster. For example, some people might need to buy food, while others might need medicine.

- Rebuild homes or infrastructure: CVA can help people buy the materials needed to repair their homes.

- Livelihood recovery: Cash grants can help people buy goods to build their businesses back.

In addition to these direct benefits, CVA helps rebuild the local economy as people spend money locally.

Find out more how CVA is used for disaster relief and recovery on the Cash 101.

Who delivers cash and voucher assistance?

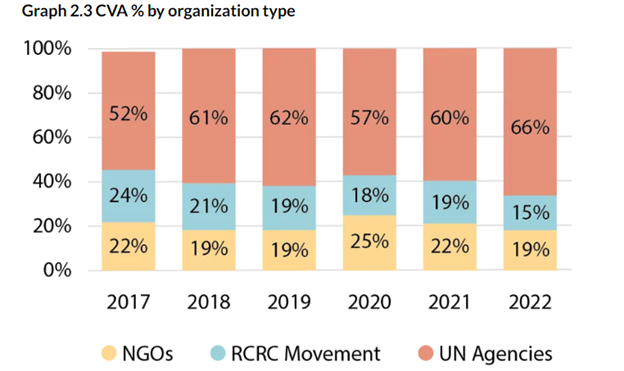

Cash and Voucher Assistance (CVA) is delivered by many actors, and through many partnerships and collaborations. However, the main types of organizations engaged in delivering humanitarian CVA are governments, local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), United Nations agencies, and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

The graph below shows the breakdown of international humanitarian CVA volumes by organization type in 2022. The graph doesn’t tell the whole story; it only shows whose accounts the funds for CVA transfers flowed through, without showing any partners who disbursed them. A more nuanced dataset does not exist, meaning that the critical role of implementing partners, many of them local and national organisations, is not reflected. Another caveat is that the graph does not consider CVA delivered by governments or local authorities via social protection systems.

Find out more about CVA volumes and roles in Chapter 2 of the State of the World’s Cash 2023.

Working with financial service providers to deliver CVA

Humanitarian actors usually work with Financial Service Providers (FSPs) to transfer cash or vouchers to recipients. FSPs include banks, money transfer operators, remittance companies, e-voucher companies, post offices and their payout agents, and mobile network operators (MNOs). FSPs are usually responsible for the actual transfer of money into the hands of recipients within CVA interventions.

In many cases, FSPs are already connected to the target community which can make transferring CVA to recipients a quick and easy process. They will be aware of the cultural, economic and legal factors that should be considered when designing the most appropriate way to transfer CVA to recipients.

When planning to work with FSPs, humanitarian agencies should carry out the following steps:

- Assess the financial literacy, technology familiarity and preferences of recipients.

- Identify existing FSPs considering local, national and global options.

- Scope the infrastructure environment to understand how cash is currently transferred.

- Identify the regulatory considerations that might affect how recipients can access cash.

- Define the CVA requirements, such as frequency of transfer, required speed of delivery and where the population is located.

CALP’s Library includes many useful resources, such as the Financial Service Provider Assessment tool and How to Map FSPs.

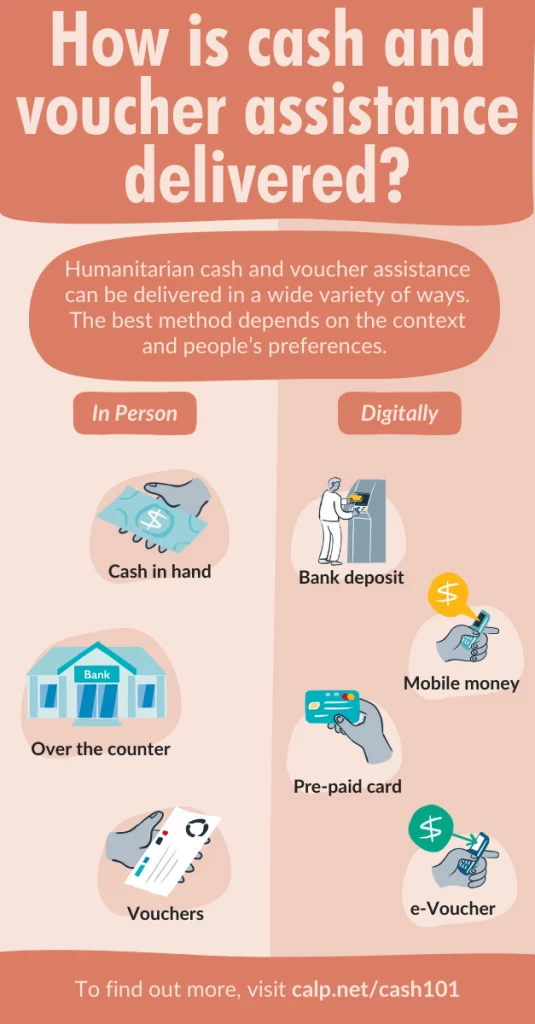

How is cash and voucher assistance transferred?

The main ways of transferring cash and voucher assistance to recipients are:

- Cash in hand: A cash payment made directly to recipients in physical currency. Transfers might be distributed directly by the implementing agency (although this is less common now than in the past), or by a third-party service provider such as remittance companies, banks or post offices.

- Physical vouchers: Vouchers are provided in the form of paper or card which can be redeemed for goods or services from participating vendors.

- Digital cash: Money sent to recipients via mobile phones, prepaid debit cards, or using another digital transfer mechanism. These transfers can be withdrawn and used as physical cash or used to make e-payments for goods and services.

- Digital vouchers: An e-voucher sent to a phone, a smart card, or a code that can be redeemed at a participating vendor.

Digital transfers are considered an effective tool to reduce diversions of aid, as there are fewer intermediaries and opportunities for corruption. Digital transfers can, if designed appropriately, also help increase financial inclusion – meaning people who otherwise lack access to financial services gain access to more formal systems.

However, it is important to be aware of and consider the data risks involved, as more personal information is typically gathered when using digital payment mechanisms.

Cash in hand or physical vouchers might be considered more appropriate for areas with little technological infrastructure, or if there are concerns about excluding recipients due to financial or digital illiteracy. The downside is that distributing physical cash or vouchers is typically labour-intensive, time-consuming, and can have security risks, such as diversion or theft. This is also true for other forms of aid – humanitarians must plan to mitigate risks accordingly.

Find out more on our page about types of CVA.

How is CVA targeted?

An important aspect of humanitarian programme design involves establishing who will receive assistance. Like any type of humanitarian assistance, CVA targeting is based on a combination of factors including the programme’s objectives, the needs to be met, demographics, and the location of those affected by a crisis. Targeting processes for CVA are not fundamentally different to other forms of humanitarian assistance as they should be determined by the programme objective and not the type of assistance.

The way targeting is done depends on the means available to identify and register people (e.g., existing lists, social registries, community-based targeting, digital platforms, etc.), and what’s most appropriate. For example, in the early stages of a rapid onset response, it may be best to support the entire target community and then reduce coverage over time based on information around vulnerability. Community engagement is crucial for effective targeting. Local leaders and community members should be involved in the targeting process to help define criteria, identify the most vulnerable, and ensure the programme’s transparency and acceptance.

If available funding cannot meet the needs of the target population, then further prioritisation and a narrowing of selection criteria may be required.

Issues to consider when targeting CVA assistance include:

- Targeting criteria: Information from needs assessments and demographic data (e.g. income level, household size, access to basic services), are considered alongside the objectives of the intervention to identify who qualifies for assistance and who does not.

- Targeting households, individuals or groups: Depending on the programme objectives, assistance can be targeted at individuals, households or groups (i.e. Group Cash Transfers). Generally, CVA interventions to address basic needs are targeted to households via an identified individual. Some interventions supporting, for example, livelihood recovery, nutrition or health, may be more appropriately targeted to individuals.

- Inclusion: Assistance can only be effective if it is accessible to the target population. For example, a programme transferring cash to people via mobile money or bank accounts should consider people’s capacity to use them and provide digital literacy training if needed.

- Technology and Data: Technology is used to support targeting, registration and disbursement processes. Management Information System (MIS) databases are used to manage recipient data securely and efficiently and biometrics have been used to verify individuals. These technologies can help prevent fraud and duplication and ensure that assistance reaches the right people. Ensuring responsible data management and effective data protection is essential.

CALP’s Programme Quality Toolkit provides detailed guidance around CVA targeting. If you would like to strengthen your CVA expertise and your ability to design and implement high-quality programming, find out more about CALP’s online ‘Core CVA Skills for Programme Staff Course’.

Determining transfer values of CVA: how much to give?

An important aspect of delivering cash and voucher assistance involves determining how much cash will be given to an individual or household – this is known as the ‘transfer value’. When talking about the transfer value, people are usually referring to the value of a single cash transfer but the frequency (how often) and duration (over what period) of the CVA also need to be considered.

Transfer values are informed by needs, what the intervention aims to achieve. Typically, the transfer value aims to supplement people’s existing resources so that they can fully meet their priority needs. To determine this, a ‘gap analysis’ might be used to quantify the gap between people’s resources and the cost of their unmet needs. Some limitations must also be considered such as the total available programme funding.

Key steps and considerations in the transfer value calculation process include:

- Assess the needs: A ‘needs assessment’ should identify both overall and unmet needs.

- Quantify the priority needs to be addressed: This can be done using tools such as the Minimum Expenditure Basket (MEB) or the Household Economy Approach (see below).

- Determine the household capacity: This is done during the needs assessment to capture any other support that households receive in addition to incomes and production (e.g., growing food).

- Identify the gaps: ‘The gap’, sometimes referred to as the ‘unmet need’, is equal to the ‘total need’ minus the ‘household capacity’ (including assistance provided by others).

- Conduct a market assessment and economic analysis: It is critical to assess and track market prices and trends, as well as factors influencing costs, availability and access. As the situation changes, then the transfer value may need to be recalculated.

- Calculate transaction or transport prices: Consider any costs the recipient might bear in accessing assistance such transport costs to get to the market, bank charges, and mobile money fees.

- Coordination and collaboration: Humanitarian actors need to coordinate with the cash working group, government agencies, local organizations, and others to ensure consistency of the transfer value.

As mentioned above, the first step to calculating a transfer value is to assess the need. Various methods are used to do this such as:

- A minimum expenditure basket (MEB) is the amount of money needed by a household to meet its basic or essential needs. It covers essential items and services that are readily available to households through local markets.

- National poverty lines reflect the cost of a basket of goods that ensures the attainment of certain minimum living standards, assessed in relation to the conditions of the country. Poverty lines are often the reference value for social protection programmes.

- Household Economy Approach (HEA) is a livelihood-based framework to determine whether households have the food and cash they need to survive and prosper at different points throughout the year. It is a relatively resource intensive approach, relevant in contexts of slow onset food and nutrition crises.

Why is cash and voucher assistance a good form of aid? Read more on the Cash 101 about the benefits of CVA.