In conversation with humanitarians: Are we doing enough to put people in crisis first?

As part of my job, I have the very interesting task of occasionally running opinion polls for our 20,000+ LinkedIn followers – all of whom have a professional interest in humanitarian Cash and Voucher Assistance (CVA).

In April we asked CALP followers this question:

It turned out that 65% of our followers strongly agreed or agreed that humanitarians are increasingly involving recipients in the design and implementation of CVA. That’s great news – it seems that there are improvements.

But then I instantly wanted to know more…why were so many people optimistic, but still a significant 35% less optimistic? Also, was the question wrong? Maybe we should have asked if humanitarians were doing enough to address this, rather than just doing increasingly more to address this.

Unpacking the results of the poll

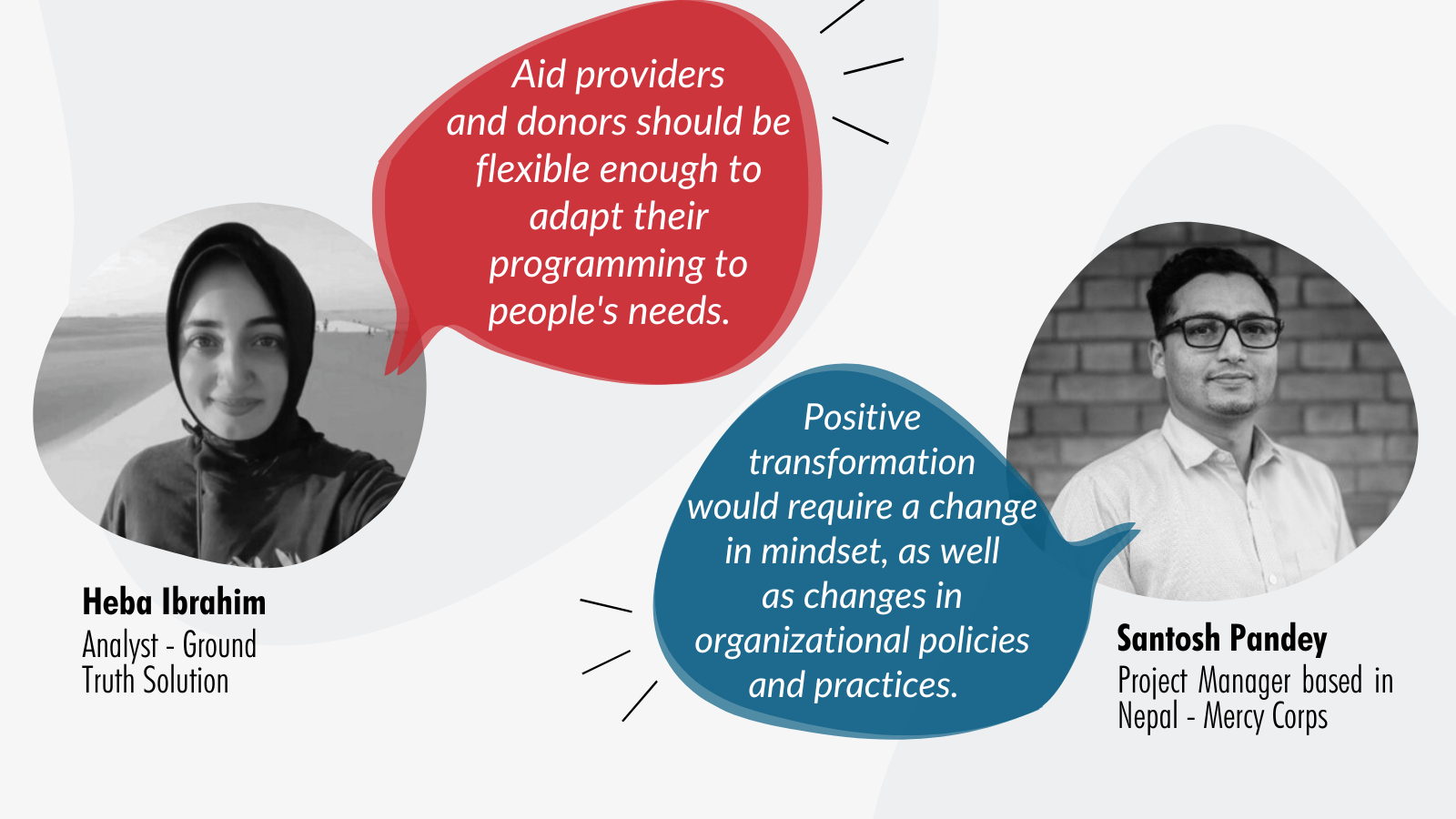

I decided to do some digging and spoke to two very interesting poll-voters who shared their thoughts:

I asked them: Do you agree with the poll statement?

Heba:

Heba felt that too often programmes failed to meet people’s needs due to a lack of consultation.

“I disagree with the poll statement. Part of our work is to engage regularly with people affected by crisis to understand their perceptions of the relevance, fairness, and accountability of aid and listen to their ideas of how things could be done better. Over and over again, people tell us they do not feel like they have a say in shaping the aid they receive. Only 39% of the cash and voucher recipients we spoke to in Somalia last year said that aid providers consulted them on their needs and less than half felt that they could influence decisions about aid. Many people feel that aid providers come to implement plans which they have developed in their offices without consulting with them or considering their needs. This often results in a waste of much-needed humanitarian support when the ‘wrong’ items are provided or when designing cash programmes that do not exactly hit the mark. For example, one participant in a recent qualitative study said, ‘when we needed food, they brought pots and pans’ and another said, ‘aid providers come and give out small cash assistance, which is not helping us’.”

Santosh:

Interestingly although Santosh felt positive about agencies prioritising the needs and preferences of communities, he did feel more could be done.

“I completely agree with the statement, as Cash and Voucher Assistance (CVA) is not a project or program in itself but rather a response tool to aid those people in need. CVA is preferred for its flexibility, dignity, and empowerment of individuals. Therefore, involving the recipients in the planning and implementation of CVA is crucial. Community engagement is also crucial because some governments may be sceptical towards cash assistance, and political acceptability is essential for which locally led advocacy and lobby is crucial.

CVA design must also consider market functionality, which is closely related to community involvement and engagement. This approach is evident in Nepal, where CVA agencies prioritize the needs and preferences of the community during the design and implementation. The recent trend of linking CVA with shock-responsive social protection and vulnerability targeting cannot be successful without community engagement. The operational conditions for the delivery of CVA, including safety concerns and the minimization of the risk of fraud, are of great concern to humanitarian agencies so the engagement of recipients is important.

Although progress has been made in involving community members and recipients in the design and implementation of CVA programs, I feel there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure that these programs are truly people-centered. Despite the efforts made by governments and humanitarian agencies, studies indicate that approximately 20% of eligible individuals do not receive assistance due to a lack of vital registration documents and not being part of the existing social protection system. This may be due to inadequate involvement of people in CVA programs.

Even though efforts have been made to involve more aid recipients in the design of aid programs, certain vulnerable groups, such as women, children, and people with disabilities, are still not adequately represented in decision-making processes.”

What did they recommend for both their fellow humanitarians, and the entire humanitarian system?

Here Santosh and Heba had a lot to say! So, I’ve condensed their recommendations down to a few bullets. You can see their full interviews here though if you’re interested.

What advice would you give to your fellow humanitarians?

|

Heba |

Santosh |

|

|

What could lead to a positive transformation across the sector?

|

Heba |

Santosh |

|

|

I found both of their inputs so insightful and considered. I hope you did too.

I’ll leave the final word to Heba who shared a quote from a displaced man in Banadir, Somalia:

‘People want to be asked about their own needs and priorities before planning any implementation. Then people can respond and raise their voices. Then aid providers should implement what was agreed, like providing food, providing healthcare or cash assistance. But the reality is that they plan and come to us with a fixed plan from the start.’

We need to leave stories such as these to the confines of history. And Santosh and Heba have some great ideas on making this a reality. If you’re interested in further reading in this area, Ground Truth Solution’s report ‘Improving user journeys for humanitarian cash transfers’, it’s a great place to start.