Rethinking vulnerability, fairness, and CVA targeting – what if we let people decide?

Humanitarian aid was once understood to be short-term support, designed to pull people out of immediate crises. Today, more than half (59%) of global humanitarian assistance goes to people stuck in protracted crises, with estimates that this will rise to 71% in the coming decade. Cash assistance hasn’t really caught up to this reality. Aid is targeted to those deemed the “most vulnerable”, even in contexts where entire communities are in desperate need. The duration of support in many contexts is largely insufficient – people stuck in decades long conflicts are receiving cash assistance for as little as one to three months.

Of course, in a world where funds are limited and new crises are frequently emerging, it feels impossible to adequately help everyone. Working with limited funds, humanitarians try to calculate who is most in need. Yet time and again, people affected by crisis tell us that they would prefer aid to go to more people in their community, even if this means that everyone would receive less. When it comes to duration, many people tell us they prefer to receive regular transfers for longer, even if the amount they receive each month is less. In essence, people want aid to be “wide and shallow” rather “narrow and deep”.

Held hostage by the minimum expenditure basket?

Transfers are largely based on a Minimum Expenditure Basket (MEB), a bundle of basic items and services that humanitarian standards determine a household to need. Many believe that providing assistance below the “minimum” level deemed necessary for survival conflicts with humanitarian principles. However, limited funding means humanitarians are often only able to provide this “minimum” requirement for a few months anyway. After that, people are on their own. We as humanitarians no longer feel accountable for a household’s income falling to an unsustainable level, because our intervention is over. If people say that more regular funds, even if they were lower, would better support them in meeting their needs, it may be prudent to listen to them.

While it is common practice to ask people whether they would prefer cash assistance or in-kind aid, people are not always consulted when it comes to duration, coverage, or transfer value. Engaging with affected communities on these issues could allow more to be done with the limited funds available.

Boosting resilience without raising costs: an impossible task?

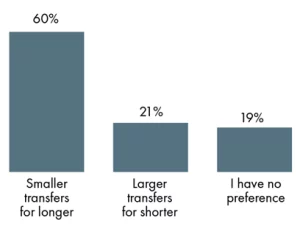

Supporting the resilience of affected communities is promised in many response plans, and in global policy agendas and frameworks, especially regarding protracted crises.  In Somalia, the majority of people we interviewed (60%) said they would prefer to receive their transfers for longer durations, even if the amount is less, versus 21% who preferred shorter durations. For the majority, receiving regular transfers over a longer period of time fosters a sense of stability. Knowing that transfers would continue for the next year or two enables them to better manage their finances and to cover their needs.

In Somalia, the majority of people we interviewed (60%) said they would prefer to receive their transfers for longer durations, even if the amount is less, versus 21% who preferred shorter durations. For the majority, receiving regular transfers over a longer period of time fosters a sense of stability. Knowing that transfers would continue for the next year or two enables them to better manage their finances and to cover their needs.

“I would take longer-term assistance over short-term. Even if it is not much, at least I know that I will be getting it for at least a year.”

– woman in Somalia, cash recipient

“I see that if the amount is small but for longer, it will help a person plan his needs accordingly, and if this month is not enough, he can plan for the next month, step by step. Now we receive money for three months, which cannot cover our needs.”

– man in Somalia, cash recipient

At a community level, many people told us they would prefer for more people in the community to receive aid, even if each household were to receive less. Here is why people might prefer longer, shallower aid:

1. Increasing coverage feels more fair

Nearly one in two Somalis needs humanitarian assistance due to recurring climate shocks, disease epidemics, and conflict-related mass displacement. We asked cash and voucher recipients in Somalia whether they prefer aid providers to target more people with smaller transfers or fewer people with larger transfers. Well over half (63%) were in favour of the first option – increasing coverage even if it meant lowering the transfer value. People’s preferences are largely based on their definition of fairness. In a follow-up qualitative study many people said that fairness meant treating everyone equally, and therefore providing aid to everyone, even if it meant that each individual would receive less, since everyone in most communities is somehow vulnerable. Data from Nigeria shows the same. When people were given two hypothetical scenarios of what a fair aid system should look like: a system that provides aid to those who need it most, or one that provides aid to everyone in the community but at a lesser individual amount, most believed that the second scenario was fairer.

“If they have 100 things to distribute but there are 600 people who may need it, what I would suggest for them is to ensure that they can reduce the quantity or even the type of goods in a manner that will go round for everyone in need.”

– Camp chairman in El-Miskin camp in Nigeria

“In my opinion, if the organisation wants to pay us 60 USD per person for 150 people, we prefer it distributes 30 USD per person for 300 people instead so that many people can benefit. It is not good if your neighbour is hungry, and only you have taken something.”

– man in Somalia, cash recipient

2. Targeting errors have less impact when more people are reached.

When resources are limited, aid providers use different targeting approaches to identify the most vulnerable. Some use poverty thresholds, while others rely on vulnerability criteria or community-based targeting. However, in many cases, to accurately identify “the most vulnerable” is a struggle. In Somalia, where exclusion based on ethnic clan membership is rife, targeting errors – according to community members – are commonplace. Increasing coverage was seen by some respondents as a way to fix this. If relatively few people are selected to receive aid in a community with high need, any inclusion or exclusion errors have a huge impact. Increasing coverage, on the other hand, guarantees that these errors are less significant.

“The issue is, if you give more money and the process is not fair, then you have just wasted money because some people who really need it won’t get it and those who don’t need it will get richer. But if you give to a lot of people, more people who actually need it will get it.”

– woman in Somalia, cash recipient

3. More coverage can better suit community norms

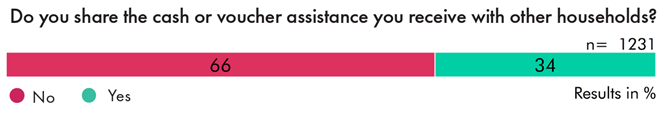

Many people in vulnerable communities share their assistance with others, to extend the support they have received with those who are equally suffering. Sharing is particularly prevalent in Somalia, where 34% of Cash Barometer survey respondents in 2022 said they share their cash or voucher assistance with other households. For many people, sharing is a cultural and religious practice which corrects for widespread vulnerability combined with low coverage of many aid programmes. When asked what aid providers could do so that they do not have to share their transfers with others, the answer was unsurprisingly to increase coverage. Even the most well-intentioned targeting approach is rendered ineffective as soon as people start redistributing aid informally, which raises big questions about the time spent developing and implementing such approaches in the first place.

“If you know the house next to you hasn’t had breakfast or lunch, you are going to share with them and likely the whole community will too. Generally, Somalis have a culture of sharing; whether you have little or a lot, you share because that’s how you get by. Somalis will always share; it’s how we have been raised and taught.”

– man in Somalia, cash recipient

“[Aid agencies] should be aware of who people are sharing their assistance with and try to help them if they can.”

– woman in Somalia, cash recipient

“They would need to support everyone they can so that people don’t feel that they need to share.”

– woman in Somalia, cash recipient

The path to a resilient future?

Despite the rhetoric on participation in humanitarian action, consultation still feels quite tokenistic. It is not enough to simply ask questions or share plans – those charged with designing and funding programmes must get more comfortable with letting people’s views and input actually inform tough decisions. In the face of widening funding gaps, much more can be done to listen to people’s preferences, and trust they know what would help them most.

Can coverage be increased in line with community preferences to reduce unnecessary redistributions? Can aid be provided for a longer period of time to give people security and allow them to plan for the future? Can cash support be layered or integrated with livelihoods support? Will any of these solutions really help people to stand on their own two feet? We’ll have to ask them.

Further reading around community perceptions on fairness, resilience, and more

Ground Truth Solutions. July 2023. Overcoming power imbalances: Community recommendations for breaking the cycle.

Ground Truth Solutions. December 2022. Rights, information, and predictability: Keys to navigating a complex crisis.

Ground Truth Solutions. July 2022. Community reflections: The cumulative impact of keeping people informed.

Ground Truth Solutions. February 2022. The participation gap persists in Somalia.

Ground Truth Solutions. June 2021. Understanding perceptions of fairness and aid modality preference.

CALP Network. August 2022. The changing landscape of cash preparedness: Real time learnings from the Horn of Africa

Author bio:

Heba Ibrahim is an analyst at Ground Truth Solutions, an international non-governmental organisation that aims to put people affected by crisis at the centre of decisions that affect their lives. One initiative at Ground Truth Solutions is the Cash Barometer, which engages with recipients of cash and voucher assistance to learn how they experience the aid they receive, and hear their recommendations for humanitarian actors.