Is cash transforming the humanitarian system or is the system limiting how cash is used?

At the State of World’s Cash 2020 launch event, Sorcha O’Callaghan, Director of Humanitarian Policy Group at ODI warned that, “Cash offers a huge transformative potential, but as far as the system is privileging the interest of the agencies over people in crisis, we won’t be able to see it”.

If you missed the State of the World's Cash 2020 launch we're sharing highlights. Quote 4 of 6 is from @sorchaoc, Director @hpg_odi, telling us the reason why coordination is such a big issue.#SOWC2020https://t.co/xHarYYdfuq pic.twitter.com/vAcodW3q7E

— CALP Network (@calpnetwork) August 6, 2020

What did she mean?

Well, as we heard from hundreds of you while putting together the report, while we can celebrate that we are delivering more cash, the promise of cash – driving a more recipient-led, flexible, leaner humanitarian aid model – is not coming good. Why? Because cash is an uneasy fit in a system that’s built along sectoral lines. If we understand and treat people’s needs in sectoral buckets, where does a tool which can meet multiple needs fit? Are we limiting the ways we use cash to make it fit in a sectoral model, around which mandates, funding streams and institutional structures have grown up?

We are often reminded that cash is just another modality for getting people what they need, not an end in itself. And this is true. But it’s a modality unlike any other, because the decision over what it’s for and what needs it will help address sits with recipients, not with donors or aid agencies. The ways we plan, deliver and coordinate assistance are predicated on the idea that we decide what people need, what they’ll receive, and judge a project’s success on whether that particular need has been addressed.

We’ve developed – for good reasons – a humanitarian system which is organized by sectors, planning, coordinating and monitoring our response to specific types of need. While this system, launched in 2005, has improved coverage, reduced duplication and improved quality, 15 years on, as CVA makes up nearly 20% of humanitarian response, it means that we struggle to find a place for, plan, fund, coordinate and capture the impacts of cash.

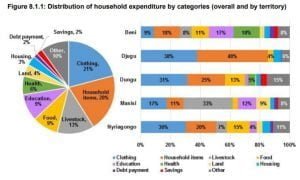

When recipients choose how to use the assistance they receive we see significant differences (a) between humanitarian agencies’ assessment of priority needs and those of recipients themselves (evidenced by up to 50% of in kind aid being sold on in some contexts) and (b) between different locations, driven by a number of factors. This graphic from a 2017 evaluation of a UNICEF CVA programme in the Democratic Republic of Congo shows the significant variation in spending patterns between people in neighbouring territories in North Kivu. Such data demonstrates a sensitivity to context-specific preferences we could not hope to replicate if aid agencies decided what would be received.

So what? In our research the issue of cash being a square peg in a round hole came up in several ways, causing a number of issues for quality CVA. Most notable and the most frequently-raised is the issue of cash coordination.

The State of The World’s Cash 2020 (SOWC2020) finds that one of the major barriers to the effective use of CVA is the lack of clarity on cash coordination. Reaching agreement on this issue has also been named as one of the four overarching priorities for the final year of the Grand Bargain, with the Eminent Person stating that confusion over cash coordination remains the “Achilles Heel of the humanitarian system” and calling for clarity. There has been very limited progress on agreeing the role, scope, leadership and resourcing of cash coordination since 2017, with particular issues around .

The SOWC2020 report shows that consider that the lack of an overall agreement for cash coordination is causing serious operational impacts

Significant effort and resources have been dedicated to trying to find a solution, but no agreement on leadership and scope has been reached. The SOWC suggests that this is because efforts have addressed the symptoms and not the root causes, which relate to issues of funding and control. Any decision over leadership and scope would be seen to create winners and losers, and any solution would require concurrent progress on joint needs analysis, another sticking point in the humanitarian system. Efforts to find resolution continue through the Grand Bargain and the Humanitarian Donor Forum, but will need to be better embedded in the broader political context.

All this may seem like such a boring, bureaucratic issue, and after years of wrangling and limited progress there are many who have had enough of hearing about it. But the SOWC2020 feedback shows unequivocally that our inability to resolve this issue is getting in the way of effective and accountable response.

And that’s the crux of the issue, and brings us back to Sorcha’s powerful statement. Cash enables us to give crisis-affected people choice and should shift the role of international actors from that of deciders and providers to facilitators of crisis-affected communities’ recovery. But we’ve built and invested in a system – on which jobs and incomes depend – which weighs against this. So the question is which force will win out? Will cash transform the humanitarian system for the better? Or will we continue to deliver cash only if and when it fits within the existing model?

The SOWC2020 shows the question is still open, but we hope that when we write the next report we’ll be able to show evidence of humanitarian actors intentionally giving up some power and control, to enable the transformative potential of cash to be actualized.