How to build a Humanitarian Response Plan that makes a difference: tips on accountability and cash

The first half of 2020 has given us few reasons for optimism. And as humanitarian planning for 2021 gets underway, relief agencies and donors will be grappling with the acute challenges of skyrocketing needs and tightening donor budgets in the midst of a devastating pandemic. The task now, more than ever before, is to ensure that every aid dollar has the greatest impact – and meets recipients’ most basic needs.

According the World Food Programme, an estimated 130 million additional people could face serious food insecurity by the end of 2020 and up to half a billion people could be pushed into extreme poverty as a result of COVID-19. The pandemic has also changed the ways humanitarians respond, with movement restrictions and distancing measures forcing new partnerships with local and community organisations, and closer government collaboration. Where humanitarian agencies are unable to reach people, various approaches – some more creative than others – are being piloted to assess need and remotely gather feedback on relief efforts.

COVID-19 provides further impetus for the scale up of cash programming. Crippling economic impacts are a primary concern in every community where Ground Truth Solutions is currently running coronavirus surveys. Public health measures make cash safer and more feasible than in-kind distributions. Many point to cash as the only way to save lives and protect livelihoods at scale. Governments are taking the lead, with new social transfer programmes in 131 countries since March.

So far, so revolutionary. But what’s all this got to do with the HRP?

Humanitarian Response Plans (HRPs) get mixed reviews. They are an uneasy compromise between the list of projects organisations would like to deliver anyway, political pressure and budget constraints. Let’s be honest: they are also a burden on coordination teams everywhere.

While we’ve got them, let’s see them as a reform opportunity.

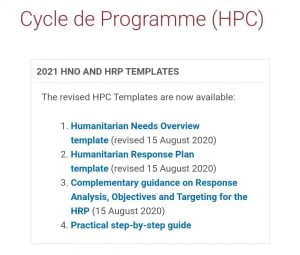

The new templates and guidance put an emphasis on joint inter-sectoral needs analysis, robust response analysis, and links with national systems.

Here are a few ideas to consider for more accountable HRPs this year:

Accountability: A response that gives people what they need, takes their opinions into account and measures quality from their perspective

A couple of years ago, the templates for the Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) and Humanitarian response Plan (HRP) were changed in small ways that could have made a big difference … if anyone had paid attention to them. The Accountability to Affected People (AAP) placeholders not only increased throughout the documents, but changed from focusing merely on planning, to seeking to demonstrate real evidence of people’s opinions. The most game-changing reform that slipped by almost unnoticed was the stipulation that perception indicators appear in the monitoring framework; for the first time, it was necessary for those coordinating the response to note how affected people saw things and to record their views as a performance metric. This has been championed by a growing number of Humanitarian Country Teams (HCTs), notably some brave early-movers in Chad, Central African Republic, Iraq, and Somalia that saw the benefit of listening systematically at the response-wide level.

The templates are online and provide better steer, from a quality perspective, than much of the present accountability guidance that focus solely on collective planning. There is a real and present danger that nicely laid-out plans in HRPs still mean nothing in real life. To avoid this:

- Include perception indicators in the monitoring framework. These can be linked to specific strategic objectives and co-developed by clusters, and/or be linked to more holistic quality goals, such as those laid out in the Core Humanitarian Standard. There are benefits to both, and the rationale behind this couldn’t be simpler: if we just ask ‘what did we deliver?’ without asking what people think, we can’t claim to be taking accountability seriously.

- A working group does not equal accountability. The hype around collective accountability has generated numerous working groups. But before such a group makes its way into an HRP as ‘collective accountability’, be sure to assess whether it’s linked to response-wide decision-making. As evaluation after evaluation has shown, working groups can’t deliver on accountability unless they have clear practical outputs, and are used to advise response leadership and operational agencies who have ultimate accountability for listening to and acting upon the feedback of crisis-affected people. Common services should help to make things practical, but that doesn’t mean the buck should be passed onto ‘accountability’ or specialist communications agencies. A good collective accountability plan in an HRP should hold everyone accountable for informing, involving and listening to affected people, and should be developed by agencies, leadership, government, donors and the HCT – not just a working group of technical communicators. Such groups should also never be islands. Accountability and cash go hand in hand, for example, and yet last year any link between the cash and community engagement / accountability working groups was only mentioned in two HRPs out of 22 reviewed.

- A plan without implementation is no plan at all. Various global reform processes have hung their monitoring hats on accountability plans in HRPs – DFID’s Payment by Results and the Grand Bargain Participation Revolution, to name two. That’s because good intentions are easy to track. But if we must limit assessment of accountability to planning, every sectoral plan should include a reference to how communities will be able to assess whether or not that plan means anything. The 2021 Humanitarian Programme Cycle (HPC) guidance asks us to, in an ‘accountability section’:

- Explain how affected people were consulted during the response planning process;

- Outline how continued engagement with communities will occur throughout the response operation;

- Articulate how community engagement will be coordinated throughout the response;

- Outline a collective approach to complaints and feedback;

- Describe how the community feedback will be used for potential course corrections in the response; and

- Outline vulnerable groups and how they will be consulted.

Doing this will already be a huge step forward for many responses (sadly), but it’s not enough. Begin with a reference to how well this went last year. If there’s meant to be a new plan every year, there must be some evidence on how efforts have gone so far. Include proof of which elements led to real community participation, or changes based on community feedback. If you can’t do that, add an extra section explaining how your new plan (with the six steps above) will be tracked. Disseminate it more widely than the HRP. Share it with key donors, and ask what they are doing to support it, to hold response leadership to account for making it happen, or to assess whether implementers at all levels are listening to those they are meant to be serving.

Cash: Building a response that strengthens local economies and maximises recipient choice

The use of cash and vouchers has doubled since 2015, now accounting for nearly 20 percent of humanitarian response. Cash and vouchers (CVA) as a tool of humanitarian assistance – where conditions and markets allow – can make a big difference. From increasing efficiency, bolstering local economies, reducing the risk of misuse and diversion, to increasing community resilience and strengthened national ownership. CVA is preferred by recipients compared to other forms of aid. But as the scale of cash increases, based on the recipients’ use, it challenges the traditional approach to response analysis and planning that works along sectoral lines.

The planning process has adapted to keep up with cash, although not as quickly or as clearly as many would like and with no clear place for cash.

Last year we set out the key cash-relevant changes to Humanitarian Response Plans, including the inclusion of an optional section on multipurpose cash. The use of so-called multipurpose cash (MPC) is growing in almost all humanitarian responses, and understanding where it’s best used and how to plan and coordinate its delivery is an increasing challenge for Humanitarian Country Teams.

The revised templates give more emphasis to the response analysis part of the process, where Country Teams collectively decide how to best use available resources to meet needs. In theory the planning process now starts from an analysis of need across sectors leading to a decision point about which needs can be met through cross-cutting responses and which require sector-specific approaches. This rarely happens in practice, and clusters take the lead in preparing sector-by-sector response plans, meaning the scope for multisectoral response is low. Cash Working Groups (CWGs) should ensure they are part of this process and should make the case for where cash – and in particular multipurpose cash – is a suitable response tool, being as clear as possible about who should be targeted, the resources required, and how this should work in tandem with sectoral responses. CWGs should understand the process, ensure they are part of it, and support response planning with all the relevant data and learning at their disposal.

Based on an analysis of last year’s HRPs and feedback from Cash Working Groups, here are a few tips (also included in the CALP Network’s Cash Coordination Tip Sheet):

- Cash Working Groups should ensure they are aware of the Humanitarian Programme Cycle (HPC) process in country and ensure they are represented at all stages. They should make the case for where cash can be used effectively to meet needs, supporting the planning processes with clear, succinct data on the cash response, including market assessments, information on targeting and post-distribution monitoring data.

- Build market assessments and other cash feasibility information into the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Show where cash is a suitable tool to meet needs and lay the groundwork for responses which support recipient choice and strengthen local markets.

- Engage in the response analysis process to understand where cash is feasible and effective. In 2020 only six HRPs referred to a response analysis process that looked at the feasibility of different options. All response analyses should use available evidence to decide which mix of modalities, sector-specific and multisectoral, are best suited to meet needs.

- Use the optional multipurpose cash section in the HRP to set out a clear plan for the use of MPC, including a target and financial requirements if possible. Last year the updated HRP template introduced an optional section on multipurpose cash. Where MPC is being used, this section can help clarify targeting, requirements, and approach. An informal review of 22 HRPs conducted by OCHA (supported by CashCap) showed that 80 percent of countries had included an MPC section , but the vast majority used it simply to describe that cash was being used across the response and to set out the functions of the Cash Working Group. To maximise impact this section should set out an operational plan and ideally include a budget line.

- Understand what national social safety nets exist and define how CVA will link to and/or coordinate with these. Building links with national systems, where appropriate, can help reduce duplication, increase coverage, and strengthen national ownership. In 2020, 16 of the 22 HRPs analysed explored links with social protection systems, although most stopped at the intention to explore linkages rather than a concrete plan. This tip sheet sets out the key steps CWGs can take to understand and support linkages.

What are your thoughts on the Humanitarian Programme Cycle – burden or opportunity? How have you used the planning process to build better responses?

Let us know in the comments below.

Main image: Refugees arriving in Ecuador who live in food insecurity receive from WFP a cash-based transfer in the form of an electronic voucher. Credit: WFP/Berta Tilmantaite. May 2016