Money, that’s what I want

People in crisis tell us they need cash, but technocrats say cash is a ‘modality’ not a ‘need’. In this guest blog, Ground Truth Solutions argue that it doesn’t matter.

It’s become a familiar scenario for us. We’ve spoken to hundreds, sometimes thousands of people affected by crisis, and we are presenting their self-described unmet needs to a room full of tired humanitarians. ‘Cash,’ we very often report, ‘is the unmet need most often cited by the people we spoke to.’ Many nod, some with a knowing smile that says ‘of course it is,’ either pleased we reported it or irritated that we would present something so obvious. But there is usually at least one technical specialist in the room who cries in horror: ‘but cash is not a need! It’s a modality!’

Some say we shouldn’t give people the option to choose cash out of a group of ‘needs’ that includes things like food or health, because cash is simply a means to get those things. Others say that letting people select cash is silly, because of course they will choose cash, but it doesn’t help humanitarians understand what their real, sectoral, aid-lingo-approved needs are. So how can they then possibly design their programmes?

But this is not a matter of asking people to choose from a list that segments their experience into neat, provider-friendly boxes.

When asking people about their needs, we don’t give them a list to choose from at all, because we want to know what they really want, described in their own words. And in their words, cash features heavily. Cash was the most-cited unmet need in northeast Nigeria, mentioned by sixty percent of people we surveyed. In Somalia, cash was people’s second most important unmet need after food. People don’t think about what they need in sectors and at GTS, neither do we. When people have suffered a shock, many – thousands of them, in fact- say that cash is an unmet need because in their lives, it is.

Take Ukraine, where people say they need cash because they can’t earn it anymore. Or Nigeria where people sell the vouchers they have been given to spend on food because they could better use the money, even at a lesser transfer value, to buy other things. In one study, 70% of Syrian refugees in Iraq sold all or most of their food rations to get money to access what they really needed. The reality is, for many in crisis, they might not know initially what they will do with cash once they get it. Needs often change quickly, and priorities shift. Something can come up unexpectedly – a health issue, a rent increase, and people know they need a buffer – cash – to deal with this. Needs and preferences vary significantly from place to place and family to family – people in crises make impossible choices, like whether to skip a meal to send an additional child to school. Those trade-offs are deeply personal. Having cash rather than a limited menu of options gives each family real choice and offers a way of delivering real people-centred assistance.

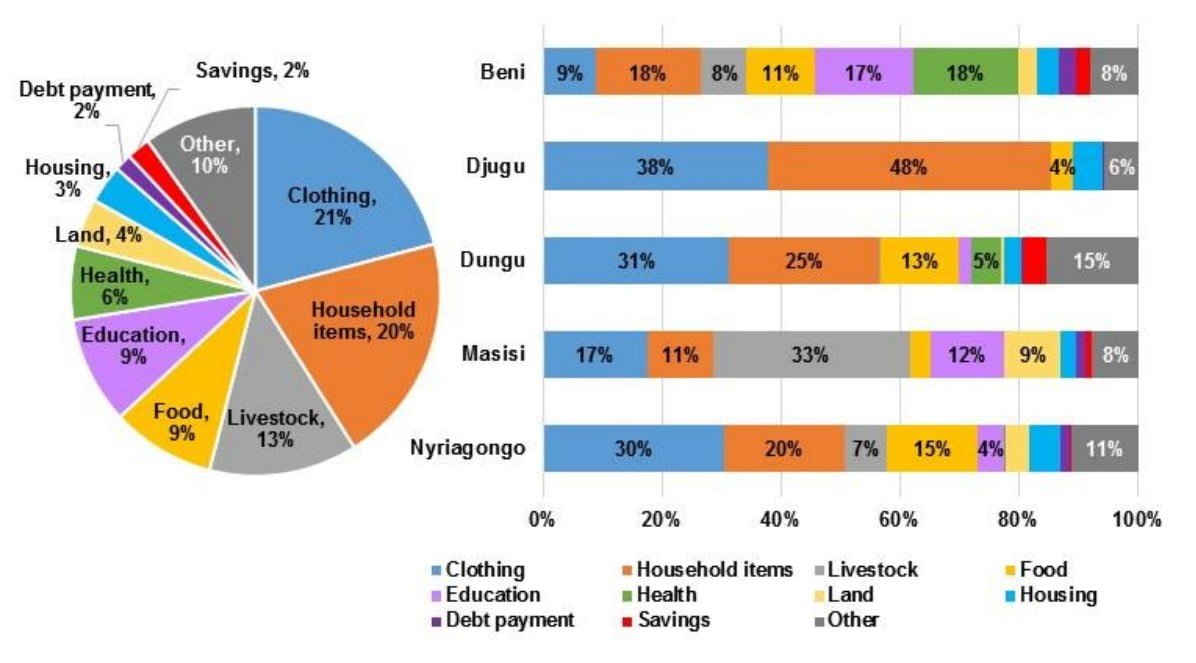

This data from UNICEF in DRC shows the huge variance in how people chose to spend cash even across a small geographic area.

“Many men are serving at the frontline in the army, so women are burdened by taking care of their families alone. Lack of money and higher prices are urgent problems, and financial aid lets people buy exactly what they need.” – Representative of the Association for Democratic Development, Ukraine.

“You know, money determines life, survival, and everything else; we want capital for start-ups, or skill-acquisition. We have businesses that we used to run, but most of us don’t have the capital to continue.” – displaced man, Borno State, Nigeria

We understand the angst of the technical specialists. They want to do their best to see that humanitarian funders and programmers understand people’s most urgent needs so they can be met. But instead of asking people to tick sectoral boxes when reporting their unmet needs, what if we simply listened? If we did, we’d hear a high proportion of people expressing a need for cash so they can define their needs as they arise, prioritise as they see fit and remain flexible as things change. For some reason, in 2023, we still find ourselves having to make the case for why cash is the answer, in an aid system where the growth of CVA is slowing in favour of more traditional vouchers and in-kind assistance.

The humanitarian system is built on sectoral lines, meaning that jobs and funding flows depend on dissecting human needs into neat boxes. But our data has long shown us the problems with approaches like ‘cash for food’ and other sectoral cash programmes that represent yet another ineffective attempt to control what people buy and how they prioritise.

And why try to control it? Not for the wellbeing of the recipients. We know that cash transfers don’t lead to reckless spending on alcohol and other “temptation goods” but in fact decrease such spending overall. Surely not to fit donor reporting templates. Most donors have led the charge for more unrestricted cash. Why can’t we just accept that we are giving people money, to use as they like, and be okay with it?

Volumes of cash delivered in emergencies have more than doubled since 2016, approaching $6bn globally. That’s good news, but cash still only accounts for around 19% of total aid provision, a far cry from the 37-42% that could be achieved if cash was used as the default modality wherever feasible and appropriate.

We need to check ourselves. If dignity and decolonisation are honest aims of the humanitarian community, then decision-making power needs to be transferred to those doing their best to steer their families out of crisis and into a sense of security. We either commit to helping them do that in line with their priorities, or we resign ourselves to a system that perpetuates power imbalances and stifles agency.

We’ve decided to listen to affected people, and not technocrats on this one. How are we ever to walk the talk about dignity, people-centred aid and power shifting in the humanitarian sector if we fundamentally don’t trust that people know what’s good for them? Is it ‘people-centred’ to ask someone about their needs, and then to tell them that the need they expressed is wrong?

So, with due respect to hardworking technical colleagues everywhere – what will we continue to do when people tell us that cash is their number one need?

We will believe them.

About the authors

Meg Sattler, Hannah Miles and Rieke Vingerling all work at Ground Truth Solutions, an international non-governmental organisation that aims to put people affected by crisis at the centre of decisions that affect their lives. One initiative at Ground Truth Solutions is the Cash Barometer, which engages with recipients of cash and voucher assistance to learn how they experience the aid they receive, and hear their recommendations for humanitarian actors.

Main image

Youlka, a mother hosting a refugee in her home, shops at the Dapaong market with money provided by WFP as part of WFP’s cash distribution to vulnerable populations affected by food and nutrition insecurity in the Savannah and Kara regions of Togo, taking her stock of fortified infant flour for the nutrition of her child aged 6 to 36 months. Credit: WFP/Richard Mbouet. April 2023.